Kailey Tedesco is the author of These Ghosts of Mine, Siamese (Dancing Girl Press) and the full-length collection, She Used to be on a Milk Carton (April Gloaming Publications). She is the co-founding editor-in-chief of Rag Queen Periodical and a member of the Poetry Brothel. She received her MFA in creative writing from Arcadia University, and she now teaches literature at several local colleges. Her poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. You can find her work in Prelude, Bellevue Literary Review, Sugar House Review, Poetry Quarterly, Hello Giggles, UltraCulture, and more. For more information, please visit kaileytedesco.com.

Read More4 Midsommar-Inspired Beauty Tips

Stephanie Valente lives in Brooklyn, New York, and works as an editor. One day, she would like to be a silent film star. She is the author of Hotel Ghost (Bottlecap Press, 2015) and Waiting for the End of the World (Bottlecap Press, 2017). Her work has appeared in dotdotdash, Nano Fiction, LIES/ISLE, and Uphook Press. She can be found at her website.

Via the Film School Rejects

A Lippie List Inspired by Fairy Tale Films and Books

BY MONIQUE QUINTANA

Fairy tales have gorgeous aesthetics. Why not paint our mouths with them? Here’s a short list of fun fairy tale art and lippies that coordinate to their fantastical colors.

1. Cartoons in the Suicide Forest by Leza Cantoral (Bizarro Pulp Press, 2016). A smart psychedelic and shocking punk rock doll of a short story collection.

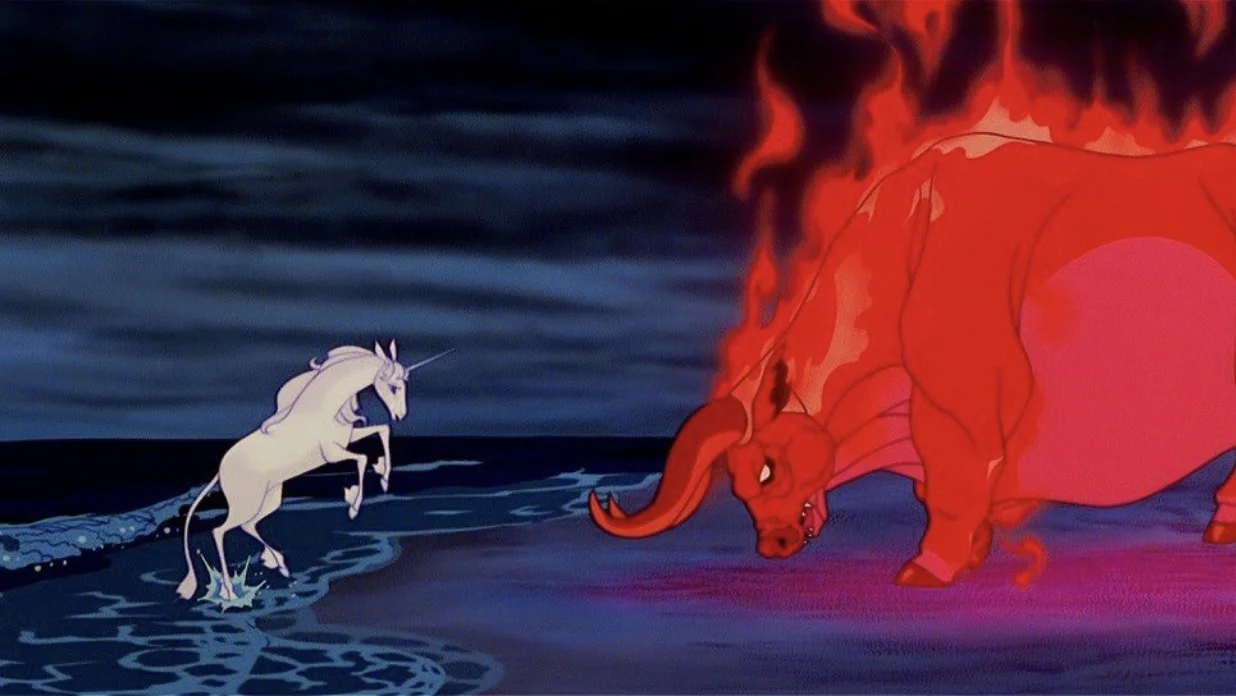

2. The Last Unicorn, 1982 A mythical beauty meets demon fantastical in this animated film adaptation of Peter S. Beagle novel.

The lippie: “Boy Trouble” by The Lip Bar

3. The Tale of Tales, 2015 A trio of dark and decadent yarns inspired by the works of Giambattista Basile make up this film directed by Matteo Garrone. Starring Salma Hayek as a monster-heart-eating queen.

4. Heavenly Creatures, 1994 Peter Jackson’s film of teenage angst, the writer’s dreamscape, and bloody matricide.

4. The Lais of Marie de France, Penguin Books. A collection of narrative poems that explore the beautiful and grotesquely shape-shifting nature of love.

Monique Quintana is a Senior Associate Editor at Luna Luna Magazine and the Fiction Editor for Five 2 One Magazine. Her work has appeared in Queen Mob's Tea House, Winter Tangerine, Huizache, and the Acentos Review, among other publications. She is a fiction fellow of the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley Workshop, an alumna of the Sundress Academy of the Arts, and has been nominated for Best of the Net. Her debut novella, Cenote City, is newly released from Clash books. You can find her at moniquequintana.com

5 Film & TV Inspired Nightgowns You Need

When I was a teen, my hobbies were a little singular. I loved moodily soaking in the bathtub in the middle of the night and wearing my pajamas well into the afternoon. Back then, this was the kind of behavior that led to my family and friends teasing me, constantly asking why I wasn’t hanging out at the neighborhood Arby’s like everyone else. But, it seems nightgowns are making a comeback (and perhaps they have been for a while now). In honor of Lana Del Rey’s new song, “hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have” here’s a list of some of my favorite nightwear in the media, and some links so you can get yourself a nightgown to tear around in well into the afternoon.

Read MoreOfficial Twitter

The Suspiria Remake Can Be Beautiful Again

Kailey Tedesco is the author of These Ghosts of Mine, Siamese (Dancing Girl Press) and the forthcoming full-length collection, She Used to be on a Milk Carton (April Gloaming Publications). She is the co-founding editor-in-chief of Rag Queen Periodical and a member of the Poetry Brothel. She received her MFA in creative writing from Arcadia University, and she now teaches literature at several local colleges.

Her poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. You can find her work in Prelude, Bellevue Literary Review, Sugar House Review, Poetry Quarterly, Hello Giggles, UltraCulture, and more. For more information, please visit kaileytedesco.com.

Read MorePhoto: Joanna C. Valente

The Complexities on Performance and Passing

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, & Xenos, No(body) (forthcoming, Madhouse Press, 2019) and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Joanna is the founder of Yes, Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. Joanna also leads workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente

Tobaccoland

Jeffrey Alan Carter is a musician, composer, and freelance sound designer living in Brooklyn, New York. He is also one of the founding members of the electronic group, SANDY. His sonic aesthetic can be described as organic yet, industrial with nostalgic shades of light and dark qualities achieved through his use of synthesis.

Read MoreVia Phassion

Lit & Fashion: Miss Havisham and Her Haunted Dress

...Miss Havisham’s dress has become her shroud...

Read MoreVia Warner

Romance Macabre: A Film List For Darklings

Because love can be nightmarish at times…

Read MoreVia Culture Trip

Winona Ryder's Misfit Fashion in Film

She's been a paradox, a popular unpopular...

Read MoreThe Love Witch is the Kitschy, Hedonistic, Feminist Film You Need to See

BY KAILEY TEDESCO

*Please note that there are some scene descriptions here, which may constitute a spoiler for some.

I found out about The Love Witch nearly a year ago. It all started with a still of Elaine Parks’ heavily shadowed eyelids and a tea dress with ruffles too glorious for words. The still became a fascination which led me to interviews with the film’s feminist auteur, Anna Biller, which eventually led me to a trailer, then back to some interviews, and so on for about nine months. It took until just yesterday for the movie to come to one of my city’s indie theaters. Usually, and in my personal experiences, a build-up of anticipation that long often results in disappointment. I remember thinking several times that this 1960’s B-Horror pastiche could not possibly live up to the hype which I, myself, have ascribed to it.

Well, dear readers, let me tell you it was worth every moment of the wait.

The film follows Elaine Parks (Samantha Robinson), a newly inducted yet gifted, member of a Wiccan coven who is quixotically obsessed (or, in her own words, “addicted) to love. After suffering years of gaslighting and emotional abuse in a previous marriage, Elaine is quickly scouted by a coven while dancing in a burlesque nightclub. From there, she quickly learns to transmogrify “sex magic” into “love magic,” but ultimately leaves each of her dalliances for dead.

The Love Witch is an open allegory with a feminist agenda. While the film’s aesthetic and score set the viewer up for the typical supernatural tropes of 1960’s technicolor horror, we are instead greeted with a more realistic sense of witches which somehow opposes and aligns with our own world’s cultural conceptions. This is because the “witch” is ostensibly equated to a sexually liberated woman, and the townspeople treat Elaine and her coven members as such. In a scene where Elaine meets up with her friend and coven member Barbara at a Burlesque show, men can be heard having discussions about how witches used to hide, but now they seem ubiquitous in society. The attitude towards witches and Wicca is mostly one of bigoted tolerance — as though witches have been publicly granted rights that the anti-intellectualist bar-dwellers can’t override, despite their disdain (sounds familiar, right?)

And the allegory grows stronger.

Elaine herself, after losing weight and gaining empowerment after her husband “leaves,” willingly codifies herself according to the male-fantasy. In the beginning of the film, she sits down to tea with Trish, a self-proclaimed feminist who has been married for ten years. After hearing that Trish will often refuse her husband of some of his fantasies, Elaine scolds that women should always give men what they want. And this is exactly what she does… or so it would seem.

Throughout the film, Elaine creates a world for herself that is heavily influenced by male-perpetuated ideas of femininity, ultimately masking herself in layers of Bardot-esque eyeliner and Audrey Hepburn LBDs. She is often cooking decadent cakes or donning renaissance gowns while riding horseback. She speaks politely and is never seen without make-up. When it comes time for intimacy, she seduces her lovers with elaborate dances in intricate lingerie. She makes herself, essentially, the embodiment of male fantasy. However, she is not quite the Stepford Wife that one might think.

She uses her beauty and sexuality as a bait for men who describe themselves as libertines or unhappily married, aka sexists. From the start of the film, she can be seen batting her eyes in what one initially assumes might be a call-back to the Bewitched nose-wrinkle. Yet, these two are largely dissimilar as Elaine is not using magic at all, simply her own sexual prowess. The men she baits are already ignobly piqued by her as they often catcall and grope. She invites herself into their lives, feeds them a philter, and suddenly they become madly (in every sense of the word) in love. What begins as a dalliance quickly turns into a literal sickness that causes these men to become hysterical with love to the point of death.

The hysterics are played for laughs and ultimately reminiscent of the ways in which women have been misogynistically portrayed in film for the past century. Elaine has none of it, immediately becoming disinterested in her own subjects and proclaiming “what a pussy.” She buries the body of one lover ritualistically, yet ultimately remains un-phased. To top it off, she places a witch bottle containing her own urine and a used tampon over the shallow grave. Her Kardashian dead-pan narration asks viewers to consider that most men have never even seen a used tampon. What she calls an addiction to love is evidently an addiction to power. Elaine exemplifies the culturally normative ideas of masculine aloofness while patronizing her dying lovers in her ruffled mini-dresses.

Anna Biller flips the typified romantic narrative while also giving the protagonist her cake and letting her eat it, too (quite literally). Elaine hedonistically enjoys all of the pleasures associated with sexist romanticism without letting the male stick around long enough for her to suffer the consequences. She flits from man to man like this in perfectly polished composure while her own paintings of liberated goddesses cutting the heart out of a man line the walls of her bedroom a la Dorian Gray. She has polarity and unity of her being, and all of her empowerment lies in her willingness to appear submissive.

Biller constructs this narrative through a carefully cultivated 60’s lens that sometimes alludes to even older Hollywood, yet the inclusion of a smart-phone at the end grounds the viewer in a phantasmagorical contemporary. The film is a world that already exists. Kubrick and Ashby and Argento are all carefully woven into it. Yet, it is not their world. Nor is it Tate’s or Hepburn’s. It is all Biller’s – a world which re-writes over a century of misogyny with one unapologetically empowered witch.

And it is fantastic. Please see it for yourself.

Kailey Tedesco is a recent Pushcart Prize nominee and the editor-in-chief of Rag Queen Periodical. She received her MFA in creative writing from Arcadia University. She’s a dreamer who believes in ghosts and mermaids. You can find her work in FLAPPERHOUSE, Menacing Hedge, Crack the Spine, and more. For more information, visit kaileytedesco.com.

Via Phantomwise

The Alice Aesthetic & What It Actually Is

I can recall a kaleidoscope of Alice.

Read MoreAnagnorisis: Rebirth in Recognizing Your Truth

My arms yearned for these strangers, these men and women who walked in the shadows of their minds, feeling alone, feeling as though they did not share a thread with any part of society.

BY S.K. CLARKE

I am a firm believer that humankind requires food, water, shelter, and intimacy. After our stomachs are full and our bodies are kept warm, we desire the ability to be seen by another human being, to be heard and understood.

The pivotal moments in my life have centered on someone acknowledging my self, the oft-guarded soul that is tucked away from casual observers. Often the other’s ability to see me results in an enlightenment; a move from shaded reality to exposed self-truth. It is important to note that this truth is not always beautiful. We may not always be ready to accept the knowledge when it is thrust upon us by the seeing few, but it is honest and bears the weight of import, all the same.

Aristotle called this moment of self-reveal or recognition, anagnorisis. Often in Greek tragedies, the protagonist is in the dark about some aspect of their being. InOedipus Rex, Oedipus was ignorant to his truth: he had killed his biological father, married his biological mother, and gave her children.

In the case of Oedipus, his understanding of self, both what he stood for and who he was in society, came with the reveal of his paternity. But what’s interesting to note, is that the audience was fully aware of who Oedipus was long before the big reveal. The Greek people were a learned audience who had seen these stories play out several times before. The Oedipal legend was old and the men who had gathered to see the play performed would have known the ending before the characters on stage would live it. The reason they went was in order to see which playwright wrote the best version; which Oedipus would spark something new within the audience.

In this I find a unique formof anagnorisis that can only be found in art: a recognition of ourselves within the creative minds of the artist.

This movement of self-knowing from the external to the internal can often be found in the paintings, the music, the poems and stories that traverse time and space to enter our psyche through the crackle of a record player or the luminescence of a Kindle screen. Lyrics and verses and compositions and brushstrokes that navigate time, space, and language to knock at the cement fortresses within our souls and say, “Hey, I know you. You are not alone.”

For me, there has been a therapy in the words of Neil Young, Billy Joel, Damien Rice, and Ray LaMontagne. Their lyrics call to me, assuring me that someone somewhere has been a miner for a heart of gold and they, too, see me in all of my vulnerability, in the darkest places where my self lies hidden from the daily world. Their careful placing of syllables and emotions finally, exuberantly, pitifully give voice to all that I’ve been wanting to say, whether I knew it before or not.

I’ve found it in the carefully constructed words of authors Sherwood Anderson, Edgar Lee Masters, and Colum McCann, the dark despair of poetess Christina Rossetti, the inspirational instruction of Brené Brown. Within the isolated activity of reading, within their solitude of writing, I found a piece of myself. A communication between myself and an unknowable stranger who, reaching across distance, reaching beyond death, declares that they see me as I am and have shared in what I have felt.

As an educator, theatre artist, and writer, I often strive for this feeling of communion with my students, aiming for them to experience the power to be known. I hope that in the pages of dramatic literature, my students and actors can say, “In this, I see me.” I hope that they can find the human in all and through that magic of recognition, they will see themselves in Stella, Ophelia, and Everyman. And, perhaps, that Stella, Ophelia, and Everyman will cause them to see humanity within themselves.

Through this seeing, this knowing, a beauteous progress is made. Stagnation is held at bay and something entirely cosmic enters into our lives, whether we expected it or not.

As an instructor, I often do not anticipate this progress to be made in my own life. I have read Hamlet no less than thirty times. For me, the recognition has already been made and now I get to enjoy those steps in my students.

However, when I began directing a play this past semester, I was shocked to find that art still had more to show me.

The play centered on the cycle of abuse within relationships, both romantic and familial. A young wife is beaten within an inch of her life and through a series of increasingly absurd circumstances, is all but forgotten by the end of the play. Both she and the brain damage she possesses are erased from the family’s consciousness. The end of the play leaves the audience with the impression that the mental and physical abuse done to her is doomed to be repeated because it has never been fully addressed.

The artist in me latched on to the uncomfortability of this, the unfinished, unpolished ending that would remind us all that abuse knows no happy conclusion. I wanted the audience to feel embarrassed and uneasy, hoping that through some self-reflection they would see abusive behaviors in their own lives and after much thought, seek to eradicate them.

The future mother in me, however, felt that I personally needed to create a positive change in the community. I needed those who I worked in and around to know that this did not have to be the answer: that cycles can end and progress can be made to heal, to repair.

Encouraged by projects such as Humans of New York and PostSecret, the drama club and I worked together to place boxes throughout the college campus, asking for students, faculty, and staff to submit their “secrets,” their moments of abuse, harassment, or discrimination in hopes that, through the sharing, they would gain back a voice they did not feel they had.

Over the course of three weeks, we received over 150 responses. A few of the posts were drawings of a penis ranging in anatomical accuracy, but the majority of the submissions were heart-wrenching confessions of disease, abuse, insecurity, and desire.

“I feel like I have no true useful purpose and no true direction,” one submission said.

One confessed: “I forgot my little sister’s birthday.”

“I suffer from claustrophobia because my father used to lay on top of me,” exposed another.

Many revealed a long-harbored affection toward their best friends while others admitted to instances of infidelity. A large majority dealt with mental illness and some confessed the wish to end their own lives. One revealed that they were HIV-positive.

My arms yearned for these strangers, these men and women who walked in the shadows of their minds, feeling alone, feeling as though they did not share a thread with any part of society. Perhaps feeling that no one could empathize. No one could understand.

But I am writing this today to tell you I do understand. I do see you. I get it.

As I paged through secret after secret, I felt an unexpected click of recognition, a cracking of my defenses, a revealing of my truth. Many of the secrets dealt with rape. Many of those same confessions were also partnered with the statement that they had not told anybody, some for many years. Some had not mentioned their abuse until they had put it down on the slip of paper I now held in my hand.

I did not submit a secret to the project, but if I did it would read: I was raped and for three-and-a-half years I believed that it had been my fault.

I was staying at a friend’s family home in Italy. My friends and their family were all tucked away in their beds. I was downstairs being raped.

The guy was placed in my path deliberately. He was supposed to be a good flirt. A morale booster. He was not supposed to sit on my chest and force himself in my mouth. He was supposed to hear me when I said no. He was supposed to stop. He was not supposed to tell me that I deserved it, that I had led him on, that I had to finish what I had started.

I was not supposed to believe him.

But I did.

For years I believed that it had not been rape. It should have been more violent. I should have had scars. If it had been rape, I would have fought harder. The only rape that counted was the violent kind, not the kind that left me asking him quietly to stop, lest I wake anyone.

And so, I remained silent. I did not speak up about what had happened, did not utter the “R” word. I did not tell my friend who had slept upstairs. She had seen me flirt with him earlier in the night and I assumed she would think I was a tease. I didn’t tell my grandmother, though I called her the minute I got back to my apartment. I wanted her to hear my voice. I wanted her to fix what had broken inside of me. She had sounded tired when she had asked me if something was wrong and I chose not to burden her. She was going through chemo after all, and I felt that I was just another whore. I did not tell my mother who holds the key to most of my secrets. I was her good girl, not a sexual being who would be found in those types of situations. In my journals, I remained dumb. In therapy, I skirted the issue.

But as I sat there, holding the secrets of strangers in my hands, I felt the crack of anagnorisis, an understanding of my truth, of what I am and what I stand for.

“I see you,” I said to the anonymous submissions. “And you see me. You never deserved this. You are not wrong. You are not dirty. You are a victim.”

I am not talking about rape culture in America, extremely prevalent though it is. I’m not going to talk about how politics and the media make it difficult for victims to come forward, as was the case in Oklahoma and Brigham Young University. I won’t mention how rape is normalized in television shows such as Game of Thrones or how the porn industry seems to capitalize on male sexual aggression against often unwilling women. Nor will I mention that out of every 100 rapes, only two rapists will go to jail.

This is about finding those men and women who are afraid to view themselves as victims, those who feel alone in their stories of abuse or harassment. You may never hold 150 secrets in your hand, but you now hold mine. What I ask is that you see that unlike the me of three years ago, I now know that I never deserved what was done to me. I also never deserved to hold it within me in silence. I’ve acknowledged that no matter what I was wearing, no matter how I had been conducting myself prior to the incident, I had not given consent. I did not say yes and something that was precious within me was taken and tarnished. I was raped.

You, too, do not need to hold yourself in the shadows.

Whether you suffer from debilitating depression, whether you have experienced rape, sexual harassment, physical or mental abuse, or dependency of any kind, you are not alone. Your secret does not make you any less deserving of love, nor does voicing it admit any weakness. Through using your voice, by putting the words on paper, or sharing your story, you can begin the healing process.

The Aristotlean definition of anagnorisis is often associated with tragedies: King Lear realizes that Cordelia’s love is the truest only after she has died, Nora’s desire for self-knowledge causes her to abandon her husband and children, Bruce Willis discovers he’s dead in The Sixth Sense.

I would like to argue that there can also be a rebirth in the recognition, a happy ending. Only through the dead of winter can we prepare for the blossoming of spring. Only from the gravel can we build a foundation. Only from the ashes can the phoenix be born again. And only through recognizing your truth can we grow, learn, and heal as a whole.

S.K. Clarke is a writer, adjunct professor, and theatre director in Pennsylvania. She has earned her MA in Text and Performance from London’s Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts and her BFA in Acting at Philadelphia’s University of the Arts. Clarke is a writer of poetry, plays, and short stories focusing on the disintegration of small-town America, social and political injustices of minorities, coming-of-age and end-of-life narratives, and stories featuring complicated and strong female characters. She is currently writing her first novel which, she hopes, will touch on all of the aforementioned topics.

Here Are Some Women Directors Whose Beautiful Work Deserves More Love

CURATED BY EMMA EDEN RAMOS

Each Women’s History Month, The Library of Congress, The National Archives and Records Administration, The National Endowment for the Humanities, The National Gallery of Art, The National Park Service, The Smithsonian Institution, and other institutes pay homage to pioneers in The Women’s Movement. As this celebratory month just came to a close, we want to acknowledge a group of female artists who deserve (more) recognition and (more) admiration. So, given that it's Friday today (which means you can Netflix ALL weekend), we are proud to offer you, our lovely readers, a “playlist” of films directed by women. Put these films on your queueor Amazon wish-list. You won’t regret it. Trust us.

Agnès Varda: Cléo from 5 to 7

"I'm too good for men."

Sally Potter: Orlando

Orlando: "If I were a man...I might choose not to risk my life for an uncertain cause. I might think that freedom won by death is not worth having. In fact..."

Agnieszka Holland: Copying Beethoven

"Forgive me. I may be a woman, but I am the best student."

Ava DuVernay: Selma

"Our lives are not fully lived if we're not willing to die for those we love, for what we believe."

Lisa Cholodenko: High Art

"I'm Greta. I live for Lucy... I mean, I live here, with Lucy."

Laurie Collyer: Sherrybaby

"From the ages of 16 to 22, heroin was the love of my life."

Deborah Kampmeier: Hounddog

“If you don’t you keep on singing, keep on feeling the spirit. If your dreams go underground for a while, buried so deep in the earth so they can survive, you just keep feeling the spirit even in the dark.”

Leah Meyerhoff: I Believe in Unicorns

“I have so much to say… but I don’t know where to start. Maybe when I learn how to breath.. I’ll know how to speak."

Emma Eden Ramos is a writer from New York City. Her middle grade novella titled The Realm of the Lost was published in 2012 by MuseItUp Publishing. Her short stories have appeared in Stories for Children Magazine, The Legendary, The Citron Review, BlazeVOX Journal, and other journals. Ramos’ novelette, "Where the Children Play," was included in Resilience: Stories, Poems, Essays, Words for LGBT Teens, edited by Eric Nguyen. Three Women: A Poetic Triptych and Selected Poems (Heavy Hands Ink, 2011), Ramos’ first poetry chapbook, was shortlisted for the 2011 Independent Literary Award in Poetry. Still, At Your Door: A Fictional Memoir (Writers AMuse Me Publishing, 2014) is Ramos' third book.

The Film Every Millennial Woman Needs to See

Lately I’ve been thinking about a recent The New York Times article about entertainment for “the Instagram age” and how this relates to Jung’s “collective unconscious” (similar now to a shared Facebook ‘feed?) and Jung’s mythical female archetypes. Somehow this inspired me to re-visit Pump Up the Volume (1990), a film that was made before social media and before Instagram. It was released in 1990, featuring kids just leaving high school and turning 18.

Read More