While the bruise of men is present in these poems, there are great alliances with women, “Sister says I touch/ and I destroy. ” The aspect of doubling is in this poetry, but women aren’t harmed by their doubles, rather, they feed of each other’s prowess. The twinning of the speaker’s self adds to the labyrinthine structure of the book, so though you encounter a new scene is each hole and crevice, there is still that familiar ache of letting go and the hope of regeneration.

Read MoreImage by Ignacio Martinez Egea

A Short Monster-Themed Reading List

**Monique Quintana** is the author of Cenote City(Clash Books, 2019), Associate Editor at Luna Luna Magazine, and Fiction Editor at Five 2 One Magazine. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from CSU Fresno and is an alumna of Sundress Academy for the Arts and the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley. Her work has appeared in Queen Mobs Teahouse, Winter Tangerine, Dream Pop, Grimoire, and the Acentos Review, among other publications. You can find her at [moniquequintana.com][1]

Read MoreChristine Shan Shan Hou In Conversation With Vi Khi Nao

BY VI KHI NAO

in conversation with CHRISTINE SHAN SHAN HOU

VI KHI NAO: How would you describe your poetry and your art (collage)? Do they seem similar to you? How close do you feel to Dadaism? Is there a particular literary movement or artistic movement you wish had been invented?

CHRISTINE SHAN SHAN HOU: I look at both my poems and my collages like miniature worlds—each filled with their own characters, tastes, textures, and elements of strangeness and love. However, I actually feel like my poetry and collage are quite different from one another; my poetry—specifically the process of writing poetry—feels heavier, darker, whereas my collages feel lighter and more directly pleasurable. Writing poetry is hard. Collaging is fun. I don’t feel particularly close to Dadaism. I remember studying them in college and being very excited at first, but now I look at them and think: Look at all those old white men! Now that we’ve seen the first image of the black hole, I wonder: What would movement look like in a black hole?

VKN: Your collection, Community Garden For Lonely Girls, shows that you have a natural linguistic impulse to produce words/thoughts that mirror each other—as if you were trying to use the rhetoric of repetition to create content by allowing it to erase itself through doubling. For example, lines such as “my ancestors’ ghosts have ghosts” (p.3), “my split ends have split ends” (p. 4), “If I lay here, how long will I lay here?” (p. 18), “Act without acting out” (p.54), etc. Do you prefer sentences/lines that never look at each other or always look at each other?

When you write these lines, I think that your poetry uses symmetry as a way to acknowledge the lexical self they haven’t been able to access; when a particular word repeats itself in the same context, it brings something out. What do you hope to bring out? In each other, meaning poetry and yourself.

CSSH: I love this question, this image, of two sentences/lines looking at each other. It brings to mind an artwork by the Korean artist, Koo Jeong A. She made this one piece called Ousss Sister (2010) where two projections of the full moon are facing each other within a very narrow space. It is so bewildering, this concept of a self without eyes looking at one’s self. Is this still considered “looking” if one can’t see? Does one have to have eyes in order to have a face? I prefer sentences that look at each other, even though my sentences don’t always have eyes. Meaning arises from the act of looking. Repetition ensures its existence. Where there is existence, there is possibility bubbling beneath the surface. When I repeat words within sentence structures I am suggesting a possibility. A possibility for what? I don’t know.

When people read my poetry their hair grows a little longer.

VKN: That is a mesmerizing image from Koo Jeong A. It reminds me of a pair of lungs. If your collages and your poems were to arm-wrestle each other and the yoga instructor/practitioner in you was forced to be the ultimate referee, who would win that tournament? And, ideally, which two aesthetic competitors would you like to see compete with each other in a match? Would you prefer to be the cheerleader or the umpire? If the winner between the two mentioned competitors (collages & poems) is the one who is able to break a reader/viewer’s aesthetic heart the fastest, which one would it be?

CSSH: My collages would definitely win! My visual art feels lighter and not so bogged down by my past, by my thoughts, or by the heaviness of the language in the air! When I make collages, I am often listening to a podcast, or music, or have a tv show on in the background, all of which feels good for my brain, whereas when I am writing poetry, I can’t have any other distractions. I have to be very in it. One could argue that this extreme awareness of the present when writing poetry seems more mindful than the multitasking of collaging, but ultimately for me, the collage process is much more enjoyable, and the yoga instructor in me will lean towards the direction of joy. I think my collages would break the reader/viewer’s aesthetic heart the fastest.

I would love to see film go head-to-head with any form of live art.

VKN: Why do you want your readers’ hair to grow a little longer? I would hope it would grow shorter, to defy the law of gravity or the law of expansion.

CSSH: Honestly, I don’t know why! It was just an image that floated into my head. I think it’s because I equate growing hair to growing older, which also means growing calmer.

VKN: You are currently a poetry professor at Columbia. Do you enjoy teaching? Would you ever play a prank on your students? If so, what would be one prank that would bring out your impishness? What collage of yours or poem of yours would be a great example of a prank? What poem or collage of yours (or someone else’s) would be equivalent to this prank? And, what is the best way for a student of the arts or in general to express rebellion?

CSSH: I do enjoy teaching. It is very invigorating to be in a room with young people who are as excited by poetry as me! However, to be honest, I prefer teaching yoga over teaching poetry. I’m not much of a prankster, but the poem that is closest to a prank is “Masculinity and the Imperative to Prove it” in Community Garden For Lonely Girls

That prank is very funny, but also mean. I think I’m too sensitive for pranks. I realize that makes me sound a little bit like a wet blanket, but I am ok with that. I think the best way for a student of the arts to express rebellion is to pursue the practice outside of the academic institution and at one’s own pace, whether that pace is a sprint or a crawl.

VKN: I view pranks as one way or a tool an artist can use to express him or herself creatively in a comedic fashion. My brother sent me that prank at a sad point in my life, and it cheered me up and made me feel closer to him. I do not view it as a gesture of meanness, as in: shampoo is just shampoo and irritation is irritation and water running down one’s face excessively once every millennium is a divine act of profound charity.

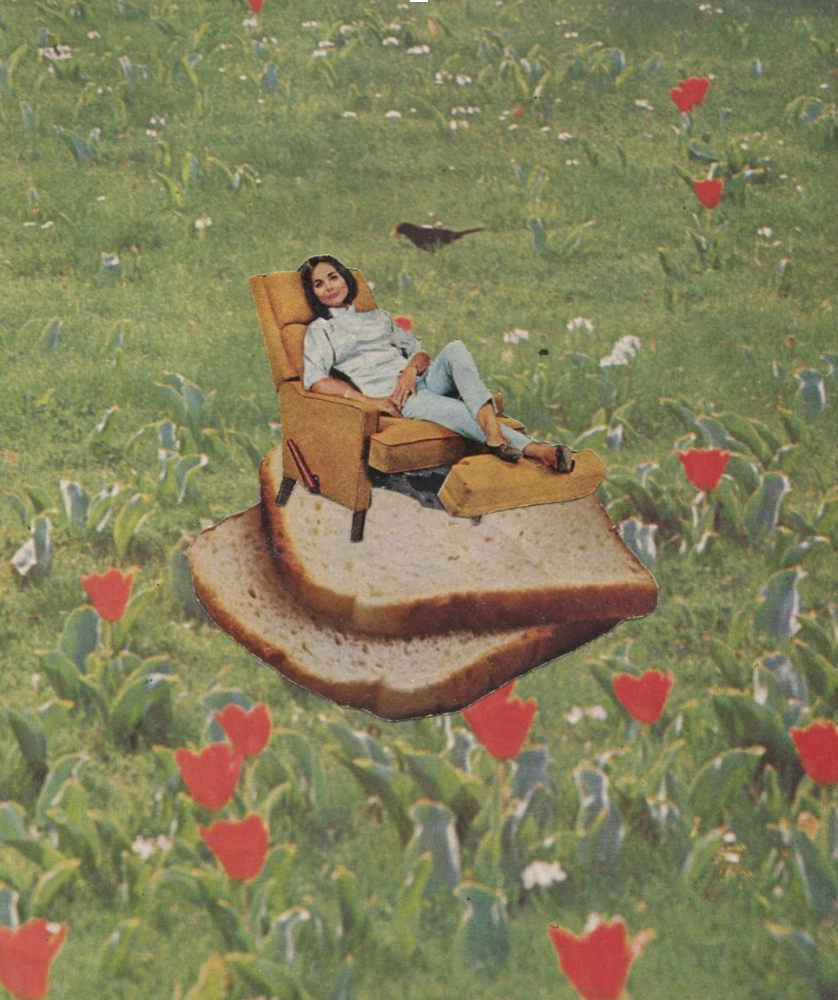

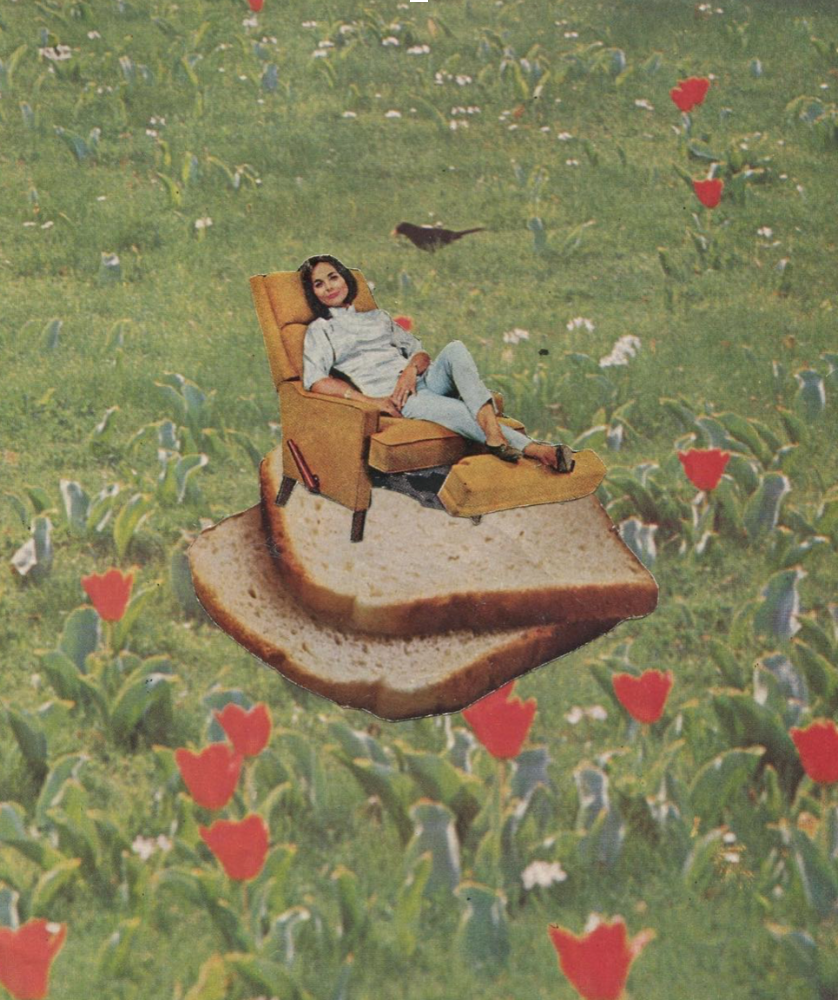

Speaking of visual or kinetic creativity, one can view your visual works on your Instagram: hypothetical arrangement. Can you talk about the piece below? Can you walk us through the process of how you created it? From seed of conception to final product?

How often do you make your collages? I know you have one daughter, but in terms of sibling rivalry (how many of you are there, btw?), has poetry ever fought with you for creative space because you devote more time to one discipline or art form rather than another? You must understand scissors and surgical knives very well. Do you ever feel like you are a surgeon? Have you ever created a collage where you feel like you are performing a heart surgery and the life of this art piece heavily depends on how well you incise? Have you ever cut through the artery of an image and felt lost or lonely or regretful or sorrowful or overjoyed?

CSSH: This collage is called “Self-actualization (in recline).” When I make collages I go through old magazines and start cutting out images that speak to me. I have several categories for images and three of them are: food, women, and seascape/landscape. I don’t remember how I arrived at this final image, but I remember liking the way the red flowers contrasted with the dreary, soft slices of bread and then the ease of the woman’s posture. I like her shimmering periwinkle outfit and her pet bird in the background.

I try to make at least one collage a week, but that doesn’t always happen. I tend to make many collages in a short period of time, or even in one sitting, and then occasionally mess with them for a few minutes every few days, until I feel satisfied with them.

I am one out of four siblings. However I do not see any “sibling rivalry” between poetry and my yoga and/or collage practice. I think they all work in harmony with one another and give each other the time and space to breathe.

Yes! I definitely feel like a surgeon when I am making collages. I use an x-acto knife so I can really get into the details. And there are so many pieces I’ve considered “ruined” or “dead” because I was too impatient with the cutting of a very precise detail. But then I immediately let it go. I try not to get too precious about paper arteries.

VKN: Will you break down the poem “A History of Detainment” (p. 72) or (“Masculinity and the Imperative to Prove it,” or why this poem may feel pranky to you) from your collection, Community Garden For Lonely Girls, for us, Christine? Can you talk about the process of writing that poem? Do you recall writing it? What was it like? Where were you emotionally? Intellectually? Were you preparing a meal? On a train? Or what piece of writing/art inspired it? Did it take you long? And, could you talk to us about this line: “While navigating the meadow of hypotheticals, I tripped and broke my arm” (p.72). If you broke your arm, what one line from a canonized poet would you want to scribble on your cast?

CSSH: “A History of Detainment” is so long and heavy and my brain is so tired after a full day of running around with my kid. But I can say a little bit about “Masculinity and the Imperative to Prove It”: When I was a child, my grandparents owned a Chinese restaurant called Oriental Court inside of a New Jersey shopping mall. Every Saturday night my entire paternal family—grandparents, all of their children and all of their children's children—would eat dinner after the mall's closing hours. After the meal, me, my siblings, and my cousins would run around like crazed little people in the empty mall and play all sorts of games including: "Red Light Green Light," "Red Rover," "What Time is it Mr. Fox?" and "Mother May I."

However, the golden rule was that we had to wait at least thirty minutes after eating before engaging in any physical activity, or you would get sick. When I was a young girl, I was often ashamed of my body. I used to wish that I were white so that I could fit in with the popular crowd; I would make myself throw up because I thought I was fat; and because I was sick a lot as a child, I would view my medical issues as a reflection of moral shortcomings. In other words, I was a very sad child. But at the end of the poem, the sad child is actually a fish. And we all know that a salad can be both a curse and a blessing.

VKN: That’s a very beautiful story, Christine. I understand your tiredness. Perhaps this last question then: What do you think is the best way for one poet to feel at home in a poetry collection by another poet?

CSSH: Poetry collections are like homes unto themselves. I think the best way for a poet to feel at home in someone else’s poetry collection is by taking their time while reading it and listening closely, attentively, to what it is trying to say.

Christine Shan Shan Hou is a poet and visual artist based in Brooklyn, NY. Publications include Community Garden for Lonely Girls (Gramma Poetry 2017),“I'm Sunlight” (The Song Cave 2016), and C O N C R E T E S O U N D (2011) a collaborative artists’ book with Audra Wolowiec. She currently teaches yoga in Brooklyn and poetry at Columbia University. christinehou.com

VI KHI NAO is the author of Sheep Machine (Black Sun Lit, 2018) and Umbilical Hospital (Press 1913, 2017), and of the short stories collection, A Brief Alphabet of Torture, which won FC2’s Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize in 2016, the novel, Fish in Exile (Coffee House Press, 2016), and the poetry collection, The Old Philosopher, which won the Nightboat Books Prize for Poetry in 2014. Her work includes poetry, fiction, film and cross-genre collaboration. Her stories, poems, and drawings have appeared in NOON, Ploughshares, Black Warrior Review and BOMB, among others. She holds an MFA in fiction from Brown University.

Photo: Joanna C. Valente

Writing Letters in the Age of Loneliness & Violence

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, Sexting Ghosts, Xenos, No(body) (forthcoming, Madhouse Press, 2019), and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Them, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. Joanna also leads workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente / FB: joannacvalente

Via the Film School Rejects

A Lippie List Inspired by Fairy Tale Films and Books

BY MONIQUE QUINTANA

Fairy tales have gorgeous aesthetics. Why not paint our mouths with them? Here’s a short list of fun fairy tale art and lippies that coordinate to their fantastical colors.

1. Cartoons in the Suicide Forest by Leza Cantoral (Bizarro Pulp Press, 2016). A smart psychedelic and shocking punk rock doll of a short story collection.

2. The Last Unicorn, 1982 A mythical beauty meets demon fantastical in this animated film adaptation of Peter S. Beagle novel.

The lippie: “Boy Trouble” by The Lip Bar

3. The Tale of Tales, 2015 A trio of dark and decadent yarns inspired by the works of Giambattista Basile make up this film directed by Matteo Garrone. Starring Salma Hayek as a monster-heart-eating queen.

4. Heavenly Creatures, 1994 Peter Jackson’s film of teenage angst, the writer’s dreamscape, and bloody matricide.

4. The Lais of Marie de France, Penguin Books. A collection of narrative poems that explore the beautiful and grotesquely shape-shifting nature of love.

Monique Quintana is a Senior Associate Editor at Luna Luna Magazine and the Fiction Editor for Five 2 One Magazine. Her work has appeared in Queen Mob's Tea House, Winter Tangerine, Huizache, and the Acentos Review, among other publications. She is a fiction fellow of the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley Workshop, an alumna of the Sundress Academy of the Arts, and has been nominated for Best of the Net. Her debut novella, Cenote City, is newly released from Clash books. You can find her at moniquequintana.com

Image via Tori Amos

Survival and Truth: How Tori Amos' Under The Pink Changed My Life

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

You don’t need my voice girl, you have your own

We were living in a poor neighborhood on the border of Elizabeth and Newark in New Jersey. I took packed “dollar cabs” to school when it was too cold to walk. We used food stamps at the little mercado downstairs, so I only went when my friends went home and I wouldn’t get caught.

On the third floor, our little apartment had two small bedrooms. Mom slept in the living room, on the couch. My mom was always either at the mall working, or out. She was working hard to overcome an addiction, and no matter how big and beautiful her heart was — the monster was winning. When she was out, I would, like a cat, keep an eye or ear open. Hearing the door knob late at night meant I could finally rest. She was home, and my body could wilt. I could sleep.

My brother and I slept on mattresses on the floor; his room got even less light than my did, so he would sit on the floor playing video games for hours in the dark. I could feel the house’s sadness all the way from my bedroom, but I didn’t have the language to manage it. The translation was lost in the heavy air, so I’d shut my bedroom door and ignore him, seven years younger than me. I’d blast my music and pretend to be somewhere else — in the woods, at the sea, wherever I could be free.

My room was my heaven. There was one long window, and that window looked out at a yard where I could watch a neighbor’s dog lounging or chasing butterflies in the summer. In the smallest of ways, everything felt fine. I could siphon that normalcy and try to press it into my chest like a lantern. I’d light it up when I couldn’t sleep.

A room is a sanctuary, an ecosystem, a confessional.For me, it was a place where I transformed from wound into girl.

Tori Amos happened to me during the summer of 1999. I’m not sure how it happened or who recommended her to me, but when I slipped the little Under the Pink disc into the CD player and sat on my bed, I grew a new organ. I was capable of metabolizing the trauma.

When my mother was out, out, out — wherever she was — or when she was in a screaming match with her violent boyfriend in the next room — I was etching Tori’s lyrics, sometimes over and over, into a little notebook.

I couldn’t possibly have understood all of it, as most of the language was either too adult or too cryptic or simply too Tori, but it spoke directly to the wound in a way that needed no translation or filter.

It was the line, You don’t need my voice girl you have your own, that I distinctly connected with. I wasn’t aware of what feminism really meant, not at all at that age or in that era, but I could feel the surge of electricity that came with being validated by a woman. I was suddenly her little cousin, and Tori was my cool older relative — all jeans and red hair exuding some strange, beautiful warmth. Or maybe she was my stand-in mother. My goddess. It was one of my first glimpses of what it could mean to look up to a woman who was full of space and light and hurt, like me, and who, through some digital osmosis could also heal and love me. Who tapped into the small dark pain and cradled it.

My mother was sick. My grandmother was dying. I had no one else I could turn to, but Tori found me in my bedroom and inhabited the space as nightlight, as cool sheets, as framed photographs of possibility.

Is she still pissing in the river, now?

Another element that struck me: the odd narratives. At this point, I was existing in the height of teen melodrama. A word could mean a million things. A lyric could mean anything I needed it to be. And an album could be the digital imprint of my entire life. I didn’t try to dissect the words, as an adult would. Instead, I fell, backwards into her words; it didn’t matter if I didn’t ‘get it’ or if I had no idea who the fuck the grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia was. I hung onto every word because my life was small and broken and dirty, and Tori gave me everything and more. Continents and ghosts and heartache I wouldn’t experience until I was older.

So, of course I’d borrow a computer at school to Ask Jeeves the Duchess, and I’d print out about 28 pages describing the whole history of her life and death. With my newfound Tori knowledge, I’d walk around the halls at school clutching her lyrics and all the weird shit the Internet said about her work as if they were holy texts. I had the secret. I had a bigness in my pocket. I had possibility and potential and the mouth of the piano whispering into my ears.

Really, as long as I had double-A batteries for my disc-man I could move through my day cushioned.

It was around this time I started writing poetry. I often borrowed themes and topics from Tori’s music, becoming obsessed by her stories of sneaking sexual acts and rebelling against religious morals — getting off, getting off, while they’re all downstairs — or her not-so-cryptic words about God — God sometimes you just don't come through/Do you need a woman to look after you? My poems might have been bad, but they turned my sad, small little bedroom into a palace of courage.

Her bravado and bravery asked me to confront things I’d been afraid to think of. For one — god. Raised in a Catholic family of Sicilian descent, the idea of God and morality and shame was stamped into me since childhood. Even if I wasn’t at church every Sunday, I’d never really heard anyone so thoughtfully critique god. (Pretty soon I’d stumble on Tool’s Aenima, but Tori got to me first).

Also round this time I was making out with bad boys who smelled like cigarettes and pulled fire alarms. I was skipping class to hang out with girls I crushed on. I was *69ing calls in the hopes it was a boy. But talking about sex with any seriousness was not the norm. Tori talked about it from the woman’s perspective, and not just in relation to getting fucked by a guy. Her frankness, especially around masturbation, positioned sensuality as something that wasn’t dirty or bad, but sacred and empowered. Reclaiming, exploratory, rebellious. Hers.

Because I started with Under the Pink, I quickly moved on to Little Earthquakes and found out quickly that she had some powerful words around sexual assault. Yet again I was able to confront the massive, festering wound that I’d been carrying around since pre-adolescence, when I was assaulted (repeatedly) by a man in his 40s.

For me, Tori Amos allowed me to inhabit myself. And myself was a place which was always kept burdened by realities far too heavy for what a teenage girl should have to carry.

Tori, for me, was like an early archetype of Hecate, my goddess of night, of ghosts, bringing me into realms where I could confront the dark. She lit the way through my journey.

The strangeness and complexity of her music, the choir girl influence, the jarring juxtapositions, her softness of anger and brightness of disappointment — it was a new language. Between those first and last tracks, an angel’s wings unfurled, alighting a bleak space.

She taught me that words — stories, poems, or lyrics — could be nuanced and odd and nonlinear, rooted in magic and not saturated in a sugary shell for easy consumption.

But most of all Under the Pink taught me that in self-truth, no matter how messy or imperfect or grandiose or weird, a whole spectrum of color could unfold. There I was in yellow, in blue, in lilac. I experienced a shadow life in color. There I was stepping out of my own dark, even for a few moments.

You don’t need my voice girl, you have your own, she said. And I believed it.

Lisa Marie Basile is the founding creative director of Luna Luna Magazine—a digital diary of literature, magical living and idea. She is the author of "Light Magic for Dark Times," a modern collection of inspired rituals and daily practices. She's also the author of a few poetry collections, including 2018's "Nympholepsy."

Her work encounters the intersection of ritual, wellness, chronic illness, overcoming trauma, and creativity, and she has written for The New York Times, Narratively, Sabat Magazine, Healthline, The Establishment, Refinery 29, Bust, Hello Giggles, and more. Her work can be seen in Best Small Fictions, Best American Experimental Writing, and several other anthologies. Lisa Marie earned a Masters degree in Writing from The New School and studied literature and psychology as an undergraduate at Pace University.

DIY Gift Ideas for The Magical, the Dreamy, and the Crafty

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

I have never — literally, ever — been crafty (excerpt with journaling — which I do, on a very basic level). When I stepped inside a Michael’s for the first time, I was overwhelmed. It was alien to me.

However, I was tasked with ‘making’ something when I working on my last book, Light Magic for Dark Times. My editor suggested creating something sweet and unique as a way to get people interested in my book.

Creative paralysis. A crafty person does not a writer make!

So, I watched some videos on YouTube, bought a few bits from Etsy, and began creating little spell bags. I used shells (many collected from the beach, some bought), sachet bags, dried roses and lavender, scrolls, and nautical trinkets — and I fell in love with the process. I made hundreds of these for my readers and potential book sellers. (Hint: book promotion is way, way harder than I ever thought it would be — I’ve got an article coming out about that soon).

So, if you like to make things with your hands, create your own gifts or DIY goodies rather than spend money on mass-produced items, or simply surround yourself with intentional and special objects, I’ve rounded up some of the best DIY gift-making videos I watched.

These will help you create dreamy, literary, and magical bits and bobs. Made with intention and care, these little beauties not only make beautiful home decor (or, as I said, gifts) but the process of making something can be meditative and rewarding.

Here we go:

Review of Christine Stoddard's 'Water for the Cactus Woman'

Christine Stoddard’s poetry collection, Water for the Cactus Woman (Spuytenduyvil, 2018) is a meditation on family, the body, and navigating a bi-cultural map of memories. The most looming figure in the poems is the speaker’s dead grandmother, who appears in the most mundane of places, bringing dread to the speaker. In “The Cactus Centerpiece”, the ghost provokes jealousy and a cactus shapeshifts from protective shield to a portal for the dead, “We never named the cactus/ or the petite panther, / even though we named/everything, good or bad.”

Read MoreVia de la Luz. Cover art is “Medusa Galáctica” by Cynthia Treviño

Review of Interstellar Bruja Vol. 1 & 2 by Rios de La Luz

…the borderlands, outer space, and the neon glow of chisme…

Read MoreOfficial Twitter

The Suspiria Remake Can Be Beautiful Again

Kailey Tedesco is the author of These Ghosts of Mine, Siamese (Dancing Girl Press) and the forthcoming full-length collection, She Used to be on a Milk Carton (April Gloaming Publications). She is the co-founding editor-in-chief of Rag Queen Periodical and a member of the Poetry Brothel. She received her MFA in creative writing from Arcadia University, and she now teaches literature at several local colleges.

Her poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. You can find her work in Prelude, Bellevue Literary Review, Sugar House Review, Poetry Quarterly, Hello Giggles, UltraCulture, and more. For more information, please visit kaileytedesco.com.

Read MorePhoto: Joanna C. Valente

The Complexities on Performance and Passing

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, & Xenos, No(body) (forthcoming, Madhouse Press, 2019) and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Joanna is the founder of Yes, Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. Joanna also leads workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente

5 Women-Centric Horror Films to Watch This Halloween

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams (Aldrich Press, 2014), The Gods Are Dead (Deadly Chaps Press, 2015), Marys of the Sea (ELJ Publications, 2016) & Xenos (Agape Editions, 2016), and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault (CCM, 2017). They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Joanna is the founder of Yes, Poetry and the managing editor for Civil Coping Mechanisms and Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in Prelude, BUST, Spork Press, The Feminist Wire, and elsewhere. Joanna also leads workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente

Visual Poetry by Vanessa Maki

Vanessa Maki is a queer writer,artist & other things. She’s full of black girl magic & has no apologizes for that. Her work has appeared in various places like Entropy, Rising Phoenix Press, Sad Girl Review & others. She is also forthcoming in a variety of places. She’s founder/EIC of rose quartz journal, interview editor for Tiny Flames Press, columnist for terse journal & regular contributor for Vessel Press. She enjoys self publishing chapbooks. Her experimental chapbook “social media isn’t what’s killed me” will be released by Vessel Press in 2019. Follow her twitter & visit her site.

Via PX

Writing Prompts Inspired By Popular Fairy Tales

…reimagining popular narratives can be both challenging and an act of resistance.

Read MoreTobaccoland

Jeffrey Alan Carter is a musician, composer, and freelance sound designer living in Brooklyn, New York. He is also one of the founding members of the electronic group, SANDY. His sonic aesthetic can be described as organic yet, industrial with nostalgic shades of light and dark qualities achieved through his use of synthesis.

Read More