An interview with Jenn Givhan

by Lisa Marie Basile

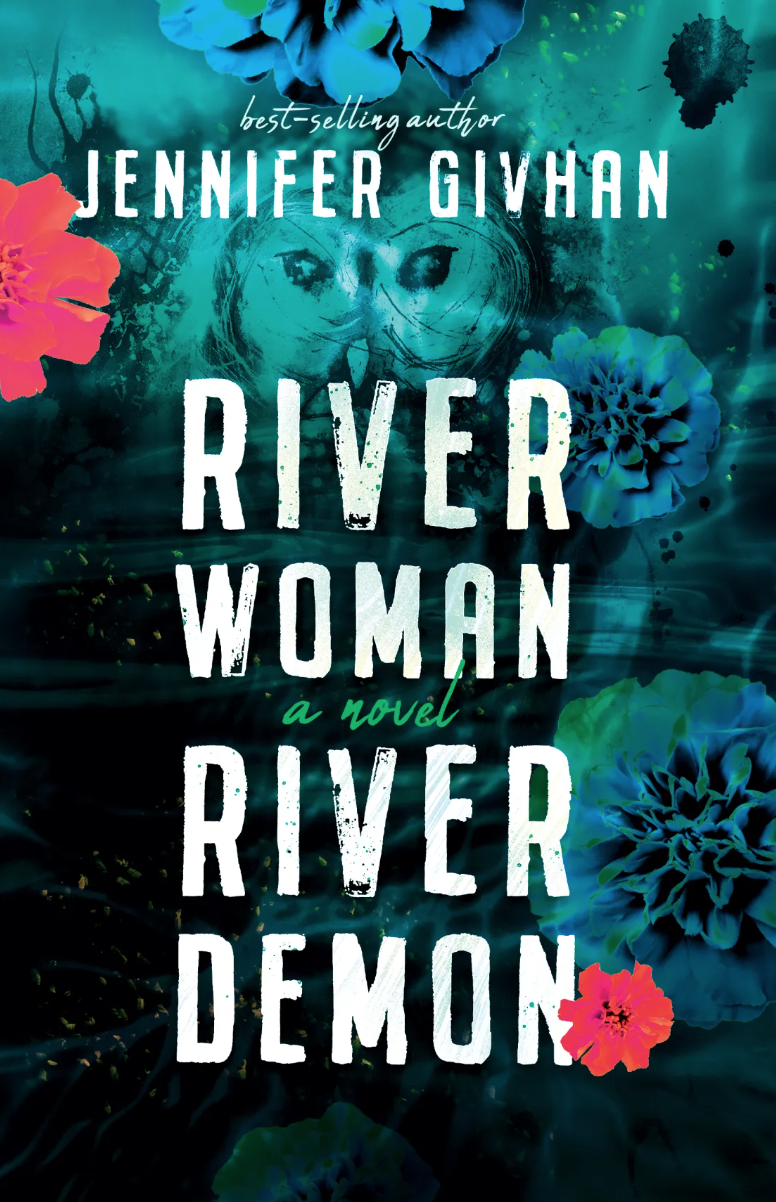

Jenn, welcome to Luna Luna! I am such a huge fan of your work — and am consistently inspired by your spirit, your ideas, and your literary and personal offerings of magic. Can you tell us all about your newest—incredibly beautiful and important—work, RIVER WOMAN, RIVER DEMON?

“Like the call to write, the call to love is ever about the marginal spaces that separate and bind us—the inky place that asks us to continue revising and reimagining, tying ourselves to this life, to each other, despite or perhaps because of the pain. ”

Eva Santiago Moon is a budding Chicana bruja—whose bruja mother died in childbirth, so Eva was raised by her conservative and well-meaning sister Alba, who isn't interested in their cultural roots of witchcraft but instead nurtures her family in the kitchen with traditional comida. Eva deeply wants a coven and mother/sister figures who likewise practice the ancient spiritual ways of brujería and curanderisma. When we meet Eva, she is the intensely depressed mother of two magickal, biracial children, a glassworking artist who hasn’t created lately, and the wife of a rootworking, hoodoo-practicing university professor, Dr. Jericho Moon, who owns a magickal shop that Eva affectionately calls "the circus" because she met him at one of his magickal showcases under billowing circus tents.

Eva is a strong, independent Latina mother deeply invested in her cultural roots but has lost her way. While many psychological thrillers focus on rich, white women, Eva is Chicana, lives in the Southwest, and is the mother of biracial children. This story focuses on the holistic spiritual and magickal practices of BIPOC people embodied through Eva and her husband, Jericho. When we meet her, she is at one of her lowest points, suffering from PTSD, depression, and a feeling of disconnect from her roots.

I’ve found that folks of color, particularly Latinx and indigenous communities, are often marginalized and overlooked in the media and literature (although I’m excited to see much more representation in the witching communities with the rise of brujería in the mainstream). We want to see ourselves represented across the genres and not just in stereotypical roles.

Eva is a fully fleshed-out protagonist, not trying to be a perfect wife or mother, with flaws and troubles that are not necessarily connected to her ethnicity and some that are—just as real Latinx folks in this country. She drinks and says what is on her mind but profoundly loves her family. She is a woman who has lost her way and will find it, a mother struggling to care for her family while maintaining her self-worth during a terrifying murder investigation.

We’ve been told to believe that darkness within ourselves, any manifestation of shadow, is our enemy, but Eva’s dark path as a bruja is the dark night of the soul (la noche oscura del alma) that leads her to deep truths and understanding that will embolden and strengthen her if she can trust herself. We need to listen to our inner voice and our ancestors’ wisdom and not let ourselves be gaslit or steered off course by society or those with skewed or selfish agendas. This story is about believing in oneself and trusting the support system one has created. As Eva comes to understand—she is the spell. Her magick is not external but internal—she's had it all along.

“We’ve been told to believe that darkness within ourselves, any manifestation of shadow, is our enemy, but Eva’s dark path as a bruja is the dark night of the soul (la noche oscura del alma) that leads her to deep truths and understanding that will embolden and strengthen her if she can trust herself. ”

The inspiration for this story came from my childhood memories and PTSD, as well as a harrowing experience with a narcissistic abuser who had me all twisted up, and I wanted to show how even smart, talented, powerful, empowered women can be susceptible to these gaslighting serial abusers. As a practicing bruja who has healed both personal and ancestral trauma in myself and my family through brujería, I wanted to share the tools and practices that have strengthened and buoyed me in an accessible way. There are many wonderful nonfiction books on magical practices and witchcraft, but I’ve found that my magic is within my imagination, so I wrote a novel.

The protective magick of this thriller is based on the actual practices of people of color, including my familial practices. It resists stereotypes even as it embraces many classic elements of psychological thrillers and magical realism — such as a character with a murky, traumatic past that blurs or muddles her grip on the present situation, a haunted character who misunderstands what the ghosts are trying to communicate, a strong woman who is being gaslit by at least one man in her life, and a woman who needs to embrace her power. When she does, she kicks some serious ass and rights major wrongs. There's also a focus on sisterhood and counting on other women rather than being jealous or turning to men for help, which all of the above stories and shows portray as well, though not necessarily together.

Even the Charmed reboot, which has so many amazing elements, tends to focus on mainstream Wicca as the central magick, even though the protagonists are strong BIPOC/Latinas. My story looks toward the magick of people of color—brujería, curanderismo, hoodoo—even as it shares many commonalities with Wicca and other Western pagan practices and beliefs.

The use of folk magick of people of color in RIVER WOMAN, RIVER DEMON is portrayed as realistic throughout, with some magical realism elements common in Latinx literature and culture to offer a grounded and realistic presentation of folk magick while still allowing for the deeper resonances of metaphor that horror and supernatural thriller audiences have already come to expect by nature of the genre, such as giving into the subconscious where belief resides.

In other words, an audience who is already primed to believe that the dead can be conjured to help solve a murder mystery is also ready to suspend disbelief about other elements of folk magick – thus, I make a case for the metaphorical aspects of folk magick and how it helps protect people of color and isn’t just superstition. In this way, I’ve alchemically fused my thematic message within the structure of the work itself—creating, I hope, a place where belief feels organic and relevant.

Can you describe your literary influences and inspirations? What is the through-line or framework through what and how you write?

My work tends toward magical realism and dark psychological motherhood that reflects on an often darker sociopolitical landscape, but the shadow work exists to reveal the light, and that’s always my goal–to shine that hopeful light amidst the darkness.

Among my influences are Toni Morison and Ana Castillo, and some of my recent faves are Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing, and Victor LaValle’s The Changeling.

In my witchy reading, I’ve enjoyed Stephanie Rose Bird’s books on hoodoo (perhaps especially Sticks, Stones, Roots, and Bones) and Juliet Diaz’s Witchery, which have helped me infuse and create my grimoire early on in my path.

I've also been reading and watching ALL the psychological thrillers I can get my hands on since I was a teenager, and lately, especially books/stories like GONE GIRL and GIRL ON THE TRAIN, all the many countless iterations. But I repeatedly noticed how often the protagonists are white women who live in metropolitan areas, often wealthy or from wealthier backgrounds.

There are very few characters of color and even fewer with major roles. As a Latina/indigenous woman raising a multiracial family, I have often felt excluded from these psychological thrillers on a social/structural level, although I am deeply interested and invested in examining women's mental health and psychological issues, including how we’re perceived, treated, and stigmatized culturally.

My goal for my writing is always to cast women of color in leading roles, active and empowered, fully constructed with flaws and issues outside stereotypes, which means that I am also interested in examining mental health issues in women of color. RIVER WOMAN, RIVER DEMON (like my second novel, JUBILEE) examines a Latina protagonist's PTSD, memory distortion, and anxiety—and contextualizes it in a larger patriarchal, abusive landscape. In many ways, I set out to write a Chicana Girl on the Train.

“My goal for my writing is always to cast women of color in leading roles, active and empowered, fully constructed with flaws and issues outside stereotypes, which means that I am also interested in examining mental health issues in women of color.”

I’m always interested in showcasing how writers approach writing — including the hard stuff, the stuck stuff, the mundane struggles, the deep emotional Work that is often neglected in conversations around the craft. Can we peak behind the proverbial curtain of your general creative process? Do you adopt any rituals while or pre-writing?

As I connected with my indigenous and Mexican Ancestors and became more invested in brujería and curanderisma, I began cultivating spaces of honoring the sacred and divine within my home and creating portable altars that I could move throughout the house in a process organic to my creative rhythms and needs as a mamawriter, meaning, my mind/heart/flow has to be fluid and in-flux to allow for the rhythms of my day as they unfold (sometimes homeschooling the kids, tending sick kids, summer days, days my kids need or crave more attention from me, as well as days I’m more chronically ill and navigating self-care needs).

So, for instance, I might set up an altar on the side of the bath where I’m taking a hot Epsom salt soak to help alleviate some chronic pain or unwind after a tough day, mentally, physically, and spiritually. Honoring the sacred with a portable altar and altars throughout my home (my work/writing/teaching space) became a reminder that we carry the sacred within us, and it’s accessible to us anytime, anywhere.

“Rest is creative. Rest is essential. Rest is sacred. ”

This also helped me forgive myself and eventually learn not to judge myself, so no forgiveness was needed because no wrong was committed when I could not write or perform a ritual or practice “self-care” in any other capacity than rest. Rest is creative. Rest is essential. Rest is sacred.

Just as the altar’s sacred space reminds me of the goddess/Spirit/Ancestors within and around me, the altars remind me of the Muse available and accessible anytime, anywhere. The altar is an invitation to openness and receptivity. If we build it, the Spirits will come. But really, the Spirits are already all around us, ready and waiting for us to quiet ourselves enough to listen. So perhaps it’s more, if we build it, we will come to what the Spirits have already fashioned for us out of stars and earth and Universe and light and truth.

In my writing, this willingness to listen to Spirit and not beat myself up that the material/concrete matter of the pub biz (publishing business) may not understand, accept, or want or applaud what I’m doing and what the Spirit/Ancestors bring me.

Because I deal with trauma-induced responses and depression and anxiety, I need a tangible reminder (lighting candles, holding crystals, and pictures of my Ancestors and Goddesses who sustain me, including Mother Mary and Frida and My Bisabuela and Coatlicue) so that I don’t feel so trampled upon that I stay down in the mud. If I’m down in the mud, Spirit is showing me the stardust to scoop up and bring back with me to the page.

The sacred that we honor (Goddess/Ancestors/Creator/Spirit) also exists within us. We honor ourselves when we honor the sacred. When we honor the sacred, we claim our value and worth as inherent and undiminishable. We are the fire we light, the crystal we hold, the prayer we utter. We are our Muse.

In this interview series, I’ve been asking writers to share how their heritage, culture, or belief system shapes their work. How do you approach writing or creativity through these lenses?

As a Mexican-American/Chicana and indigenous writer from the Southwestern border, my work explores how we can create safe spaces through the traumas of mental illness, racism, violence, and abuse against women. I strive to speak the multivalent voices of women I grew up with: the mothers, daughters, childless women, aunties, and nanas who have become my voice.

My work concerns many Latina women's complex relationships with family—it is both a liberating and subjugating force, buttressing and repressive, mythical and real. I explore the guilt, sadness, and freedom of mother/child relationships: the sticky love that keeps us hanging on when we’ve no other reason but love. I read Beloved as a young teenager, and every day before and every day since has been marked by the idea that you are your own best thing.

Like the call to write, the call to love is ever about the marginal spaces that separate and bind us—the inky place that asks us to continue revising and reimagining, tying ourselves to this life, to each other, despite or perhaps because of the pain.

All my creative work tends to mother because it comes from a place of reclaiming and healing. My work recites my mother’s chant she sang to me and now I sing to my children when they’re hurt: sana sana colita de rana, si no sanas hoy, sanas mañana. Translated literally, it asks a frog’s tail to heal. Of course, a frog’s tail, if cut off, grows anew. My work asks for impossible healing. And then makes it possible.

Who are some writers or organizations that you’d love to shout out?

Authors Publish

Irena Praitis

Rigoberto González

The NEA

The PEN/Rosenthal Emerging Voices Fellowship

Van Jordan

Lynn Hightower

Leslie Contreras Schwartz

I could go on and on – I ADORE the writing community and am immensely grateful daily.

Was there an a-ha moment that led you to write or create? Was there an experience that reaffirmed what you do and why?

I was in the book section of Target perusing thrillers with my family and discussing cover art for my novel RIVER WOMAN, RIVER DEMON when a tween girl turned the corner and shyly asked, "Excuse me, but I overheard, are you a writer?"

Me: "I am!”

Her: “Oh my gosh, that’s so COOL!”

So then, I asked her: "Are YOU a writer?"

She shrugged and said: "Well, I mean, kind of."

I looked at her with what I hoped was all the confidence I've pulled to myself since I was a young girl & said: "You ARE. I know you are."

Her: "You're right, I am."

This isn’t the moment I began writing, of course. This was just a few months ago. But our pasts, presents, and futures are connected, so imagine this is also me saying this to myself as a young, traumatized bruja, a young girl with no one to teach her or guide her in her Ancestral magic, but with a mama who loves her fiercely. Imagine this is Spirit holding this conversation in the seed of myself, waiting for the right season to bloom. Imagine that future bloom carrying me through the darkness.

My tween daughter Lina and I write middle-grade fiction together; we’re now finishing a novel to send to our agent, Rebecca Friedman. My daughter is the other future iteration of my creation that reminds me who I am—the Goddess with me always, within me, always, as a seed, an egg, waiting. Wise. Witchy. Wonderful.

What's your biggest piece of advice to someone who might be embarking on a creative journey like yours?

Mija, your journey is your own, and let no one veer you from the brightest light shining within yourself, guiding your way. You don't need anyone else's rules or guidelines, or input. Yes, we need companions and helpers and sisters and friends. Wise guides sometimes. Our Ancestors. The Spirits.

But we are also our wise teachers. Versions of ourselves are yet to bloom.

For too long, I've worried about what others think, and in the publishing biz, it's too easy to get steered off track and onto others' paths. In Capitalism, we're taught to pin our worth to earnings, product, output, and money.

Even in the creative world, the contest and competitive and prestige models can make us forget what's truly important – always, always, the creating itself.

As Eva says in RIVER WOMAN, RIVER DEMON:

"Many people think there is a clear-cut between lightwork and dark, the way so many misunderstand curanderas and brujas, thinking of healers versus Witches, as though healers are a positive force and Witches a negative. On the one hand are medicine folk, who pray to god and Mother Mary and the Saints and intercede to remove the malcontent of those who would use their power for darkness; on the other hand, are brujas who deal in curses and hexes and death.

The lines are not so drawn. Light and shadow are not binaries nor poles but are sourced from the same spring of energy.

When we stand beneath the cover of forest canopy away from the sun’s heat, the shadow that keeps us cool is not an entity created by itself, nor has the light ceased to shine.

Shadow can protect us. Darkness, too, has its blessings.

Brujas know this. Mama knew this."

What seems like a shadow path is sometimes necessary and invaluable. Trust yourself. Trust your light and shadow. Creation happens during both phases. Mija never stops creating. You are all of creation, waiting. Let go of fear. Let go of shame. Let go of anyone else’s opinions or advice. Let go of this advice. And create.

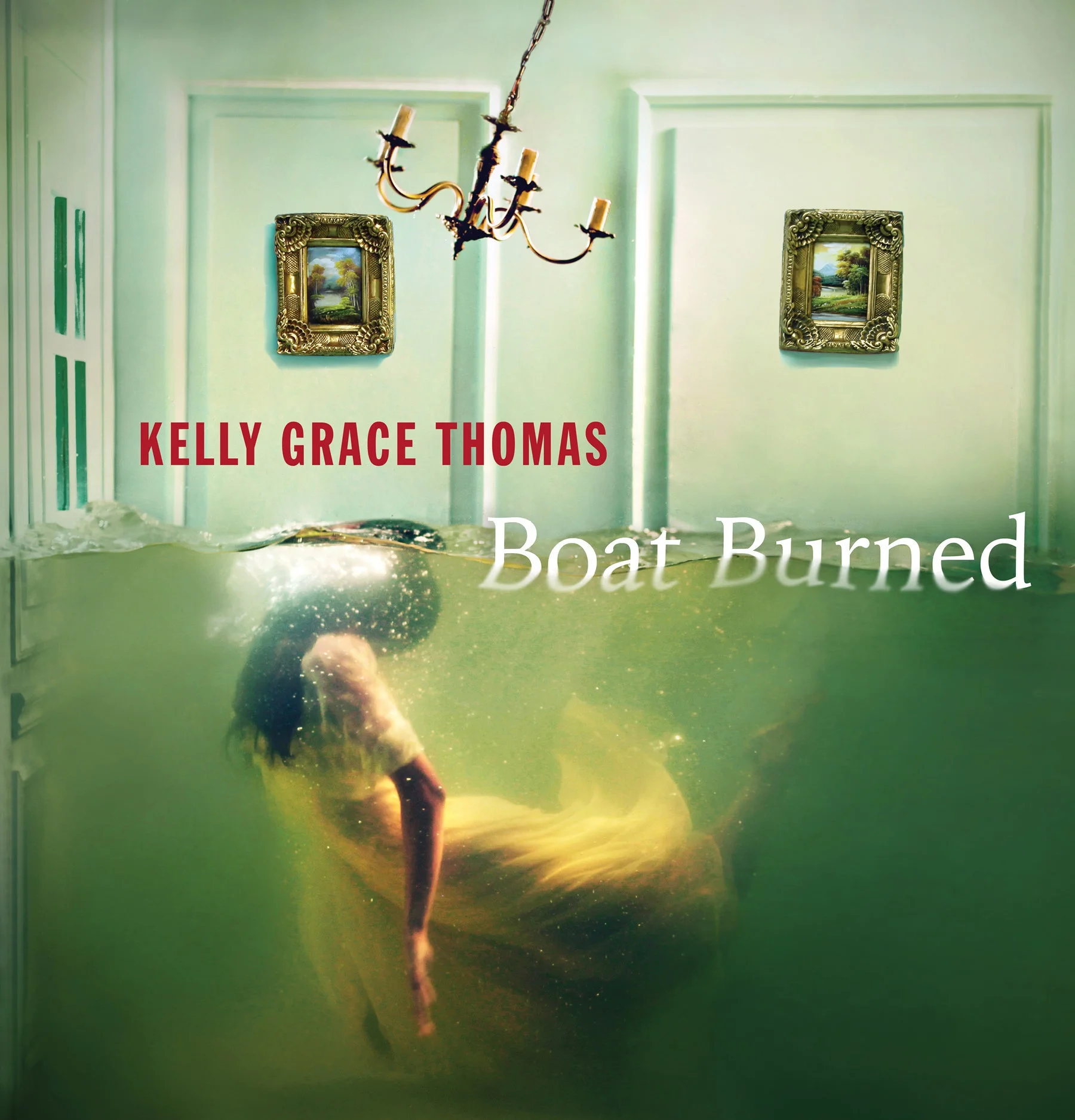

Jennifer Givhan is a Mexican-American and indigenous poet, novelist, and transformational coach from the Southwestern desert and the recipient of poetry fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and PEN/Rosenthal Emerging Voices. She holds a Master’s degree from California State University Fullerton and a Master’s in Fine Arts from Warren Wilson College. She is the author of five full-length poetry collections, including Rosa’s Einstein (University of Arizona Press) and the novels Trinity Sight and Jubilee (Blackstone Publishing), finalists for the Arizona-New Mexico Book Awards. Her newest poetry collection, Belly to the Brutal (Wesleyan University Press), and novel River Woman, River Demon (Blackstone Publishing), drop this fall 2022. Both new books draw from Givhan’s practice of brujería. Her poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction have appeared in The New Republic, The Nation, POETRY, The American Poetry Review, TriQuarterly, The Boston Review, The Rumpus, Salon, and many others. She’s received the Southwest Book Award, New Ohio Review’s Poetry Prize, Phoebe Journal’s Greg Grummer Poetry Prize, the Pinch Journal Poetry Prize, and Cutthroat’s Joy Harjo Poetry Prize. Givhan has taught at the University of Washington Bothell’s MFA program and Western New Mexico University and has guest lectured at universities across the country.

Jenn would love to hear from you at jennifergivhan.com, and you can follow her on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter for inspiration, writing prompts, and transformational advice.