Emmalea Russo’s books are G (Futurepoem) and Wave Archive (Book*hug). She has been an artist in residence at the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council and the 18th Street Arts Center, and a visiting artist at The Art Academy of Cincinnati and Parsons School of Design. She has shown or presented her work at The Queens Museum, BUSHEL, Poets House, Flying Object, and The Boiler. She is a practicing astrologer and sees clients, writes, and podcasts on astrology and art at The Avant-Galaxy.

Read MoreWeekly Mantras for Badass Witches

Stephanie Valente lives in Brooklyn, New York, and works as an editor. One day, she would like to be a silent film star. She is the author of Hotel Ghost (Bottlecap Press, 2015) and Waiting for the End of the World (Bottlecap Press, 2017). Her work has appeared in dotdotdash, Nano Fiction, LIES/ISLE, and Uphook Press. She can be found at her website.

Author V. Castro Talks About Latinx Screams Anthology

Monique Quintana is a Xicana writer and the author of the novella, Cenote City (Clash Books, 2019). She is an Associate Editor at Luna Luna Magazine, Fiction Editor at Five 2 One Magazine, and a pop culture contributor at Clash Books. She has received fellowships from the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley, the Sundress Academy of the Arts, and has been nominated for Best of the Net. Her work has appeared in Queen Mob's Tea House, Winter Tangerine, Grimoire, Dream Pop, Bordersenses, and Acentos Review, among other publications. You can find her at moniquequintana.com and on Twitter @quintanagothic.

Read More4 Midsommar-Inspired Beauty Tips

Stephanie Valente lives in Brooklyn, New York, and works as an editor. One day, she would like to be a silent film star. She is the author of Hotel Ghost (Bottlecap Press, 2015) and Waiting for the End of the World (Bottlecap Press, 2017). Her work has appeared in dotdotdash, Nano Fiction, LIES/ISLE, and Uphook Press. She can be found at her website.

You’re Supposed to Drown Witches by Nikkin Rader

BY NIKKIN RADER

You’re supposed to drown witches

But sometimes their gramarye is too strong

or because they can fructify, you salt their roots

what spells can be mussitated or what cities can be clogged by a nimbus

or aura too bright, why birds ululate in the morning

A daymare rising to breeze as if summerfruit or floral berrying,

slicing thru even the gravid among us, incogitant in its mechanizing ruth

To suffer them a living is a damning offense, before a lashing at wooded phallus

forest infertile in their soil by fire

A terror on gender and sucking into vortex, its evil sighting,

to be marked by deviling mammary ridge

a press for paper to burn

Nikkin Rader has degrees in poetry, anthropology, philosophy, gender & sexuality studies, and other humanities and social science. Her works appear in Drunk Monkeys, Coalesce Zine, Perfectly Normal Magazine, the sad bitch chronicles, Silk + Smoke, Recenter Press, Occulum, Pussy Magic, and elsewhere. You can follow her twitter or insta @wecreeptoodeep

Poetry by Danielle Rose

BY DANIELLE ROSE

Variations on Drawing Down the Moon

it is about drawing things in. i want

to be tree-roots / & lightning

striking an open field.

how first i open myself like the face

of the moon / so that i become

the face of the moon.

& into me flows the face of the moon.

goddess / descend into me

through me into the earth.

it is about remaining open like how

i want to be tree-roots / to hold

you both hopeful & ashamed

that i may be unfaithful / i imagine

that i am tree leaves & they

drink in the moonlight

& into me flows the hungry moon.

goddess / projection / demon

whatever just enter me now.

this is how you drink

divinity / & perhaps why

tides swell. in both there is dancing.

arms toward the sky / you drink god

then she seeps out again.

this must be how

we can bear to be so empty / so

we can be so full / so we can be tree-root

drawing ourselves into the moon.

On Dancing

these are the skills i never quite understood / the idea of celebration

like a trip to the dentist / i understand how out of place i am

awkward everything elbows & shoulders / awful at blowing out candles

& my wishes were just beads of sweat a sudden dampness

a stumble / because this was how i was taught to dance

to step on others’ toes / but i am not awaiting extradition

i am learning how to belong to where i am / because this is the way a sewing needle

becomes a sword / & how i stitch together myself a dance

Danielle Rose lives in Massachusetts with her partner and their two cats. She is the managing editor of Dovecote Magazine and used to be a boy.

Poetry by Laura Paul

BY LAURA PAUL

Laura Paul is a writer living in Los Angeles. Previously, her work has been published by the Brooklyn Rail, Coffin Bell Journal, Entropy Magazine, FIVE:2:ONE, Shirley Magazine, Soft Cartel, Touring Bird, and featured at the West Hollywood Book Fair and Los Angeles Zine Fair. She is the author of Entropy's monthly astrology column, Stars to Stories, and since June 2018 she's been filming a weekly video series of her poetry at poemvideo.com. She was raised in Sacramento, earned her B.A. from the University of Washington, Seattle, and her Master's from UCLA where she was the recipient of the 2011 Gilbert Cates Fellowship. She can be found on Twitter and Instagram as @laura_n_paul.

MIDSOMMAR’S Hårgalåten and the Ritual of Dance

BY MARY KAY MCBRAYER

*SPOILERS*

I have to confess something about Ari Aster’s new movie Midsommar: I did not identify with or even like Dani until she chose to set her boyfriend on fire. Before you judge me as a vindictive arsonist/murderer, hear me out. Most of my re-alignment with the protagonist is because of the ritual of dance.

I have been a dancer for all of my life—one of my earliest memories is being in a pink leotard at three years old and hearing my instructor say, “If you ever lose your place, just listen to the music. It will tell you where you are.” She meant that we should listen to the counts to situate ourselves in the choreography, but I didn’t take it that way, not even then. There’s something really special about being able to lose yourself in a piece of music, especially when the music is live. It shuts off the rest of your brain and makes you live in your body, and you kind of forget everything that is happening if it isn’t the dance. And when you finish dancing, everything falls in its place.

I remember at one convention I went to, the keynote speaker (Donna Mejia) asked the crowd, “How many of you feel like you are wasting time when you’re dancing? That you should be doing something else?” Nearly everyone raised her hand. “Now, how many of you are only truly happy when you’re dancing?” I did not see a single hand go down.

Sure, it sounds like a lot of existential gibberish if you haven’t experienced it—but let me ask this, more relatable question: have you ever been drunk and lost yourself on the dance floor of the club? (Look at me in the face and tell me you have never suddenly heard the end of a Prince song and realized you were grinding on a stranger in the corner. LOOK ME IN THE EYE. And tell me that.) My point is, when we hear someone is a dancer, we think they are a performer, but that is not necessarily the purpose of dance, not spiritually, and not in Midsommar.

Another confession: most of my dance training is in Middle Eastern dance, which is very different from Swedish dance, but the folk music and dance, and the purposes of it, are not necessarily THAT different. For example, belly dancing originated with women dancing for and with other women. There was no one watching. There was no audience. Everyone danced. It was a form of community. It’s the same community you feel dancing in the kitchen in your pajamas with a couple of close friends. That feeling, the one of being among your friends and doing your hoeish-est dance with a spatula in one hand is the BEST, and it’s what we see in Midsommar with the Hårgalåten. In my experience, that’s when you really start dancing, when you forget that people are watching, listen to the music, and express it in your physicality.

When women dance like that, we don’t care what we look like because no one is supposed to be watching. If they are watching, they don’t stop dancing to do it. And that’s powerful. No one is watching me. Everyone is dancing with me. I am dancing with everyone. No one is watching me, and I don’t care what I look like. (Great performers are the ones who harness this and utilize it onstage, even though there ARE people watching.) You can see the moment that Dani realizes the happiness that come with the May Day dance in Midsommar. It is the first time she smiles in the whole film.

So many of us, too, think that dancing is about the viewer, but it just isn’t. Not on a fundamental level. Sure, dance can be a performance, but that, to me, is not its purpose, and it’s definitely not the purpose of the movie Midsommar’s dance sequence. To me, the purpose of the whole May Day/May Queen dance around the May Pole is to show Dani her true family.

These women embrace her, they let her be a part of their dance community, and that’s so powerful—I’ll never forget the first time a dancer pulled me into the circle of a folk dance. It was magic. I, like Dani, glanced away a couple times to see if anyone was watching.

She wants Christian to be watching, but he isn’t. It seems like she EXPECTS to be sad that he is not paying attention, but then her dancing becomes even more joyful, more spiritual. (You can see this emotional fortitude, though not joy specifically, in spiritual dance rituals around the world, from the Whirling Dervishes in Turkey to the Moribayasa dance in Guinea to the May Day Hårgalåten celebration in the movie Midsommar.)

In the Hårgalåten, the women ARE having fun, though. Though it’s a competition, they are not really competing. Or at least they are not competing with each other.

In the folktale of Hårgalåten, the devil disguised himself as a fiddler and played a tune so compelling that all the women in Hårga danced until they died. In the version that Midsommar tells, the dance ritual is a reenactment of that myth. The women knock each other down because they’re shrooming so hard they run into each other when the music changes. They aren’t mad, though, when they fall. They tumble down, laughing, and roll out of the path of the remaining dancers. The last one standing, one of the villagers says to Dani, is the May Queen.

The May Queen, in the context of the film, has some pretty dark and ominous foreshadowing around her. I assumed, at the first appearance of that archetype, that the May Queen would be sacrificed, and I think that is what the film wants us to assume. That is not, however, what happens, and I was glad of it. (So much of this film is not what I expected it to be, and that is a delight among formulaic horror movies.)

Even the song of the Hårga is told from the first person plural, the “we” of the dancers. They are all invested in the ritual. If one of them wins, they all win. When Dani is the last dancer standing, her new family celebrates with her. They are there for her when she grieves her boyfriend, too.

I love the ending of Midsommar because I feel like Dani really comes into her own; it’s the first time she’s had agency or presented with a choice, in my opinion, throughout the film. As you know, the May Queen is not sacrificed as many of us likely intuited: instead, she’s lifted on a platform and carried to her flower throne. She follows the sounds of another ritual though her now-sisters advise her against it. They go with her anyway. She sees her boyfriend having sex with someone else. She hyperventilates. Her new family is there, with her, breathing with her and comforting her in an empathy so physical it’s uncomfortable to the viewer.

Then, Dani discovers that the May Queen gets to choose the final sacrifice, from between Christian and a member of her new family. She chooses her boyfriend.

Here’s the thing, though: I don’t think she chooses him because he’s “cheating” on her. That ritual, to me, is absolutely a rape, for one. That Christian has a terrible time at the festival is a gross understatement, but the thing to remember is that Christian was shitty way before they came to Sweden, and Dani, like so many women complacent in their relationships, women clinging to a dysfunctional relationship because the rest of their world has crashed, women set adrift from the world, clings to him like a life raft, even though he will not keep her afloat.

During the dance, Dani finds support, love, joy, and that is (in my interpretation of the competition) why she wins. It’s not until she finds that community in Hårga, specifically in the dance with the other women, that she can release the last tether to her unhappiness and set him on fire.

Mary Kay McBrayer is a belly-dancer, horror enthusiast, sideshow lover, and literature professor from south of Atlanta. Her book about America’s first female serial killer is forthcoming from Mango Publishing, and you can hear her analysis (and jokes) about scary movies on her blog and the podcast she co-founded, Everything Trying to Kill You.

She can be reached at mary.kay.mcbrayer@gmail.com.

Powerful Mantras for Badass Witches

Stephanie Valente lives in Brooklyn, New York, and works as an editor. One day, she would like to be a silent film star. She is the author of Hotel Ghost (Bottlecap Press, 2015) and Waiting for the End of the World (Bottlecap Press, 2017). Her work has appeared in dotdotdash, Nano Fiction, LIES/ISLE, and Uphook Press. She can be found at her website.

Read MoreA Dreamy Playlist for Summer

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, Sexting Ghosts, Xenos, No(body) (forthcoming, Madhouse Press, 2019), and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Them, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. Joanna also leads workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente / FB: joannacvalente

Review of Anna Suarez's 'Papi Doesn't Love Me No More'

While the bruise of men is present in these poems, there are great alliances with women, “Sister says I touch/ and I destroy. ” The aspect of doubling is in this poetry, but women aren’t harmed by their doubles, rather, they feed of each other’s prowess. The twinning of the speaker’s self adds to the labyrinthine structure of the book, so though you encounter a new scene is each hole and crevice, there is still that familiar ache of letting go and the hope of regeneration.

Read More'Trans Monogamist' Is the New Web Series You Need to Watch

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, Sexting Ghosts, Xenos, No(body) (forthcoming, Madhouse Press, 2019), and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Them, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. Joanna also leads workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente / FB: joannacvalente

3 Poems You Need to Read This Month

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, Sexting Ghosts, Xenos, No(body) (forthcoming, Madhouse Press, 2019), and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Them, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. Joanna also leads workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente / FB: joannacvalente

The Playlist Perfect for Libras

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, Sexting Ghosts, Xenos, No(body) (forthcoming, Madhouse Press, 2019), and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Them, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. Joanna also leads workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente / FB: joannacvalente

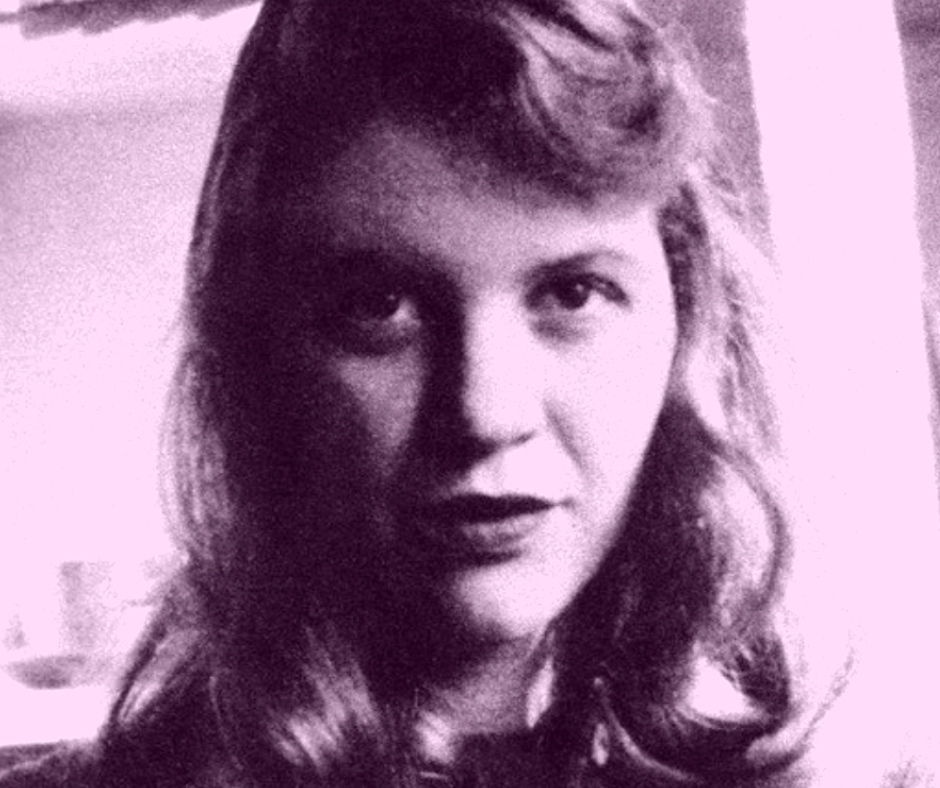

Wearing Sylvia Plath’s Lipstick

BY PATRICIA GRISAFI

The dutifully hip girl behind the register at the Chelsea Urban Outfitters was sporting a ravishing shade of reddish, hot pinkish lipstick.

“That’s a great color,” I said. “Who makes it?”

“It’s by Revlon. The color is called Cherries in the Snow. You really can’t forget that name, can you?”

I stopped by Duane Reade on the way home and picked up a tube, knowing full well that the lipstick would end up in the heart-shaped box in the closet where all my other lipsticks went to die.

You know how some women wear lipstick every day as a matter of routine? They can apply a perfect lip while riding a bike, walking a tightrope, or herding ten unruly toddlers. I’m not talking about beige-y pinks or fleshy nudes, but serious, bright, punch-you-in-the-face colors.

I’m not one of those women.

Time and time again I’ve proven incompetent at the simple task of applying a lipstick that isn’t the color of my lip; usually, I look like someone’s grandmother in Fort Lauderdale on her fifth Valium and third Mai Tai. Still, every few months, I’ll give a new color a whirl only to frown in the mirror and return to my trusty mess-proof staple since the 90s: Clinique Black Honey.

Would Cherries in the Snow convert me?

I stood in front of the bathroom mirror and carefully drew on a bright, pinkish-red grin. Then I fussed a bit, cleaning up the lines with a Q-tip and some concealer. I cocked my head to the side, bared my teeth like a hyena. I imagined myself tooling around the East Village in white Birkenstocks and large black sunglasses, with a bouquet of bodega peonies in one hand and a coffee in the other. I’d give a breezy, hot pink smile and everyone would think I was quirky and chic.

By the end of the week, Cherries in the Snow was in the heart-shaped graveyard of lipsticks past.

The next time I heard of Cherries in the Snow was in a book. Pain, Parties, and Work by Elizabeth Winder details poet Sylvia Plath’s harrowing experience as a guest editor for Mademoiselle in the summer of 1953. Readers will recognize many of the events Plath writes about in The Bell Jar as based on the details of that summer: getting food poisoning, figuring out fashion, suffering from depression.

There’s one mundane detail that Plath doesn’t include in The Bell Jar: her preferred lipstick: “She wore Revlon’s Cherries in the Snow lipstick on her very full lips,” Winder writers.

I thought I knew an absurd amount about Sylvia Plath. As one of my earliest and long-standing loves, I’ve read and re-read her poems and fiction, written about her work in my Doctoral thesis, visited her homes in both Massachusetts and London, even touched her hair under the careful eyes of the curators at the Lilly Library, Bloomington. But I had missed this small, seemingly insignificant detail.

Revlon has manufactured Cherries in the Snow for the past sixty two years; it’s known as one of their “classic” shades, along with another popular color, Fire and Ice. It’s a cult item, a relic from another era when most women wore lipstick faithfully (a fun but gross tidbit from Winder’s book: one 1950s survey revealed that 98 percent of women wore lipstick; 96 percent of women brushed their teeth). The color isn’t exactly the same as it was when Plath wore it because of changes in industry practice, but it’s pretty damn close.

I scrambled for the heart-shaped lipstick box and sat cross-legged in front of it, fishing around for Cherries in the Snow. I held the shiny black tube in my hand like Indiana Jones held the idol in the beginning scenes of Raiders of the Lost Ark. The lipstick seemed different, changed. Imbued with special meaning. I swiped on a coat, this time imagining how Plath might have applied her makeup, what she might have thought as she looked back in the mirror. Did it change her mood, feel comforting, bestow power?

People are interested in discovering the mundane habits of their favorite singers, actors, writers, and artists. They might even purchase a product based solely on a celebrity endorsement. I’ve always been interested in finding out what products my favorite dead icons used, as if I can access a part of their lost inner lives by slathering on Erno Laszlo’s Phormula 3-9 (one of Marilyn Monroe’s favorite creams) or spritzing myself with Fracas (Edie Sedgwick’s signature scent). Wearing Cherries in the Snow allowed me to experience a strange intimacy with a writer I admired, even more so than reading the very personal things Plath wrote about — including how satisfying scooping a pesky glob of snot from her nose feels.

Ultimately, Cherries in the Snow did not become my lipstick, but I gained an appreciation for the shared ritual with and strange connection to Plath that it allowed me to experience. So many of the artists who have influenced our lives are gone; it feels comforting to find a bit of their essence in something as tangible as makeup.

Patricia Grisafi is a New York City-based freelance writer, editor, and former college professor. She received her PhD in English Literature in 2016. She is currently an Associate Editor at Ravishly. Her work has appeared in Salon, Vice, Bitch, The Rumpus, Bustle, The Establishment, and elsewhere. Her short fiction is published in Tragedy Queens (Clash Books). She is passionate about pit bull rescue, cursed objects, and horror movies.