Kailey Tedesco is the author of These Ghosts of Mine, Siamese (Dancing Girl Press) and the forthcoming full-length collection, She Used to be on a Milk Carton (April Gloaming Publications). She is the co-founding editor-in-chief of Rag Queen Periodical and a member of the Poetry Brothel. She received her MFA in creative writing from Arcadia University, and she now teaches literature at several local colleges. Her poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. You can find her work in Prelude, Bellevue Literary Review, Sugar House Review, Poetry Quarterly, Hello Giggles, UltraCulture, and more. For more information, please visit kaileytedesco.com.

Read MoreMagical Thinking: Finding a Way Back to the Body

BY JENNIFER BROUGH

“To tell the truth is to become beautiful, to begin to love yourself, value yourself. And that's political, in its most profound way.”

Autumn arrives, at last, in explosions of red, orange, and yellow. Night creeps in sooner and small crackles of change electrify the air. Leaves fall echoing circular motions of death and, soon enough, gentle rebirth. In a year so fractured with continual threats to life, through health and politically corrupt structures worldwide, the seasonal shift and recently passed samhain provide much-needed anchors in times that are easy to feel adrift in.

Realising that the year is almost over, I am - as I imagine others will be - still trying to find footing against a backdrop of low-level anxiety, violence on a global scale, and fears of what the future will unveil. As the natural world is entering its cycle of decay, I feel a growing sense of invigoration. In addition to enjoying my favourite season and kindling flames of inspiration from the work of activists, artists, and writers, I am now fully recovered from a long-awaited operation for endometriosis. As my body is expanding in its range of capabilities, I feel not a sense of return to myself, but a new series of openings slowly unfolding.

Dissociation

Many chronic illness sufferers will be familiar with Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor, and the “kingdom of the well and the kingdom of the sick”. The former is all around us, institutionalised in gyms, doctors’ surgeries, stores, and diet plans. The wellness industrial complex has extended its tendrils into every area of consumable content, promising continual health - or the idea of it - in exchange for clean eating, charcoal, burpees, and multiple other methods. This kingdom feels even larger when you stand outside its drawbridge, and my ushering into the other, bleaker realm was not a gentle one.

Six years ago, I woke in blistering pain. I showered, vomited, and, bent double, phoned the National Health Service helpline for advice. A suspected ruptured appendix later became a twisted fallopian tube cutting off the blood supply to my right ovary. An uncommon, deeply uncomfortable event. That night in the hospital bed, as I swam in a tramadol haze, the pain suddenly stopped. The surgery was the following morning, but by then the ovary had ‘died’, as the surgeon told me post-op. She explained that, “a normal ovary is white, like a golf ball, but yours…” then showed me a photograph of a purple apple-sized mass. “Oh, right,” I replied, mentally adrift. “You can still have children,” she assured me, but it was hard to accept this token of relief. I asked what they did with the ovary, wondering if it had already been burned away or was floating in a jar somewhere. I don’t remember her exact answer, but the word disposed bubbles up.

Since that incident something internal had shifted and, a year later, the pain resumed. The officious surgeon I sat across from mentioned the possibility of endometriosis and scheduled another operation. She was right. The endometriosis was mild, ablated away, and I was stitched up and sent home. I remember taking the bus back from the hospital feeling that familiar separation. After another physical removal of infected tissue, I felt a mental removal from myself. I tried not to dwell in that darkening space.

The problem with endometriosis, however, is that it can grow back at any time - even if managed with hormones. I, like many other people living with it, have become a minor expert in this condition, advocating for bodily autonomy and the best course of treatment. The process is disheartening and tiring, and can make the body feel like an uncooperative machine. In living with endometriosis, alongside fibromyalgia, my body became a source of blame. It was the reason my social life suffered, intimacy became strained, and it acted as a brake on any form of spontaneity. Only recently, after much therapy, I realised the need to reclaim my body, to learn to live in it, as well as with it, anew.

Division

After my most recent laparoscopy, suspended between waking and dreaming, I saw two dark green frogs sat on my chest. Their glassy eyes looked up unblinking. When I came around properly, I searched for what the appearance of frogs in dreams mean - transformation and renewal. Sometimes metaphors write themselves.

Despite the chronic nature of this illness, transforming my thinking beyond a binary approach to wellness has been necessary to keep going. Pain and its management are seldom either/or states. Instead pain is shades of a spectrum; some days are manageable and I am active, others are better suited to staying in bed. I initially resisted identifying myself as ‘disabled’, believing I was unworthy of the designation. Part of this emerges from a need to categorise phenomena in our search for meaning - to define something as this or that - but also a lifelong struggle with being ‘enough’. Redefining how I see and accept myself is overdue, an act that won’t be completed quickly.

Part of this redefinition extends outside of self-care to how I’ve come to define the concept of care as a collective verb. Feminist movements have been historically predicated on group efforts, in which each person has a role and is supported by others. As the pandemic presses on the most vulnerable in our society, mutual aid groups have organised food parcels, rent strikes, and fundraising in the absence of meaningful action from governments. The patient/doctor experience also operates on a similar top-down structure, and I have been bolstered by finding virtual communities and friends through online spaces of care. We’ve exchanged tips and tricks when in those medical offices, signed each other’s petitions, and created art centred around disability. The latter especially has been particularly restorative. Not only do these projects offer artistic and experiential solidarity, but give us the room to indicate towards the worlds we desire, a vague map of how we write them into existence.

The three division mark scars I bear on my pelvis serve as a reminder of the necessity to collapse separation between several areas; be it the medical either/or of the kingdoms of the well and the sick; the dissociation between acknowledging and responding to the needs of my body; or the experience of sickness as an individual, instead of a part of a shared group.

Deep Diving

Outside of these groups and creative practices, two friends and I have formed a coven. A place where we mostly watch horror films, discuss tarot, and share memes and art. On the day of the most recent new moon, my friend led a ritual of letting go and rebirth. Over Whatsapp, we spent half an hour meditating, writing down what we hoped for, and what we wanted to purge ourselves of. After folding our papers up tightly, we burned each piece. I felt my body move as I breathed, where pain niggled and how it sat in relation to the rest of my being. Something shifted.

Perhaps not as intense as The Craft, but our coven’s ritual proved deeply emotional nonetheless. Not just because of the things we ablated, but the act of carving out time for oneself and others frees the subconscious to become unstuck. Allowing oneself to take time and reveal desires to ourselves forfeits certainty. More so, it allows vulnerability. To feel what it means to really inhabit the bodies we are in. In these small sacred acts, there is room for the chaotic, the uncontrolled, and this is deeply liberating.

A few days after the ritual, I came across a line from the poet June Jordan:

“To tell the truth is to become beautiful, to begin to love yourself, value yourself. And that's political, in its most profound way.”

I interpret telling the truth as a continual, reflective act, a mode of being to carry in each place we occupy - alone or as part of a group. Telling the truth about how the world is, and how you are within it, allows the lines of stability and categoriSation to blur. Telling the truth is, as Jordan says, a process of becoming. For me, it has been recognising that while I have muted these inner feelings of loss or disappointment, they always catch up. In leaning into the darker parts through meditative moments and online spaces, I can feel the raw nerve endings of bodily acceptance pulsing, and possibility glitters.

Jennifer Brough is a writer and editor living in London. Her work has most recently appeared in perhappened, Artsy, and Barren Magazine. She curates creative submissions for Sisters of Frida, an experimental collective of disabled women. You can find her on Twitter @jennifer_brough or jenniferlbrough.com.

Photo: Joanna C. Valente

What Is Sacred Self-Care?

Stephanie Athena Valente lives in Brooklyn, NY. Her published works include Hotel Ghost, waiting for the end of the world, and Little Fang (Bottlecap Press, 2015-2019). She has work included in Witch Craft Magazine, Maudlin House, and Cosmonauts Avenue. She is the associate editor at Yes, Poetry. Sometimes, she feels human. stephanievalente.com

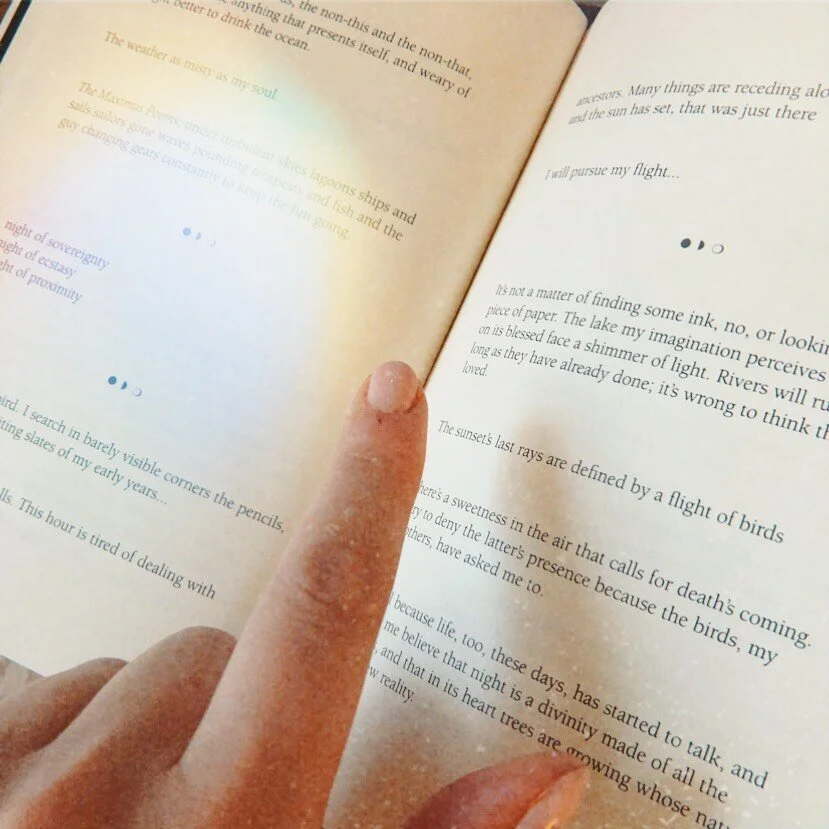

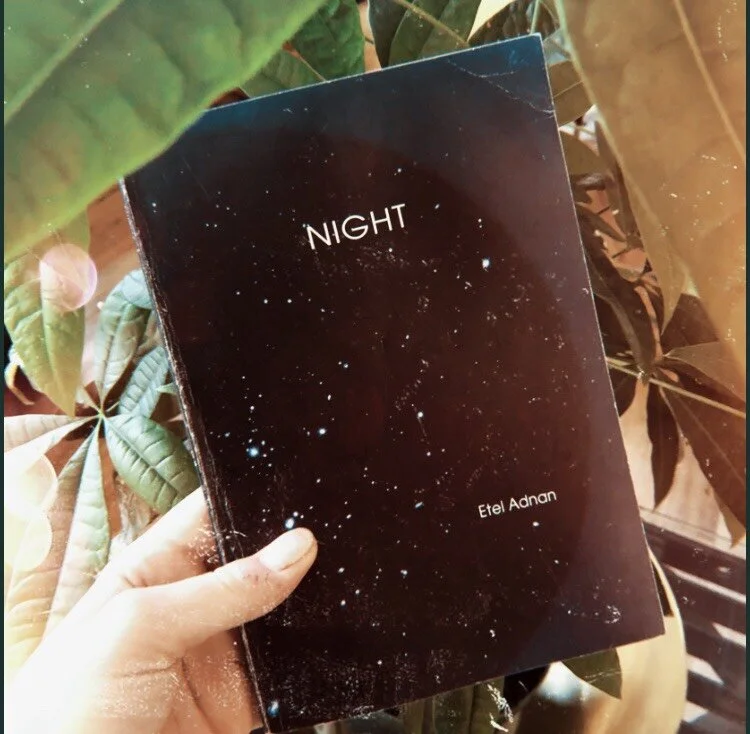

Read MoreBibliomancy with Etel Adnan’s Night. Image by Lisa Marie Basile.

Bibliomancy Horoscopes: Divination With Etel Adnan's Poetry

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

Books speak to us, create worlds for us, and conjure both the questions and answers that reside within us. When we turn to books and written texts for some greater message, a message from beyond the page, we become literary witches — or bibliomancers. Bibliomancy (which goes by many other names) is the use of books in acts of divination. The goal here is to find greater wisdom, to lean into that Force or Spirit beyond and yet within the page.

Like the ancient practice of sortes (also a form of cleromancy, the use of lots for divination), the practice of divination from drawing a card or other object, bibliomancy has long had a place across cultures and in many folk traditions. Bibliomancers traditionally used the bible for divination, although grimoires and other sacred texts were also used.

According to the University of Michigan’s Romance Languages and Literatures, poetry — how delicious! — was consulted as well. The Dīvān of Ḥāfeẓ, a collection of ghazals written by the great Persian poet Hafiz, was used to seek “Tongue of the Unseen,” or messages via the poet after his death. Today, it’s still common for people to use sacred texts, like the I-Ching or the Bible to divine wisdom.

When we use poetry, of course, there is a technical term for that: Rhapsodomancy. However, bibliomancy seems to cover it for most people.

There’s even a fun intersection of the modern and the ancient over at the Bibliomancy Oracle, a simple webpage that offers up lines of poetry after concentrating and opening a “book” by clicking a button on the site. My poetry has even been included! The site says, “This Oracle selects passages from its database using a random generator. The idea being that meaningful texts are offered via synchronicity. The relevant message finds you. You only need to be open to receiving it.”

I’ve been consulting books for wisdom long before I knew what I was doing. I’d thumb through Bluets by Maggie Nelson or Rumi’s work — seeking wisdom, motivation, a message — and poetry never failed me. I’m sure you’ve done this, too, perhaps subconsciously. Not reading, per se, but seeking. Stumbling upon a stanza. It wasn’t until a few years ago that I began intentionally meditating on a question before selecting a passage and journaling about the line or stanza I’d be directed to upon asking it.

Like tarot or astrology, bibliomancy asks us to lean into the mystery and examine what we’ve been told. What is revealed? What does this revelation ask of us? What sings out when we see the words before us?

In this practice, the reader opens a book, whatever book calls out to them. As a poet, I prefer poetry. The reader then may call out to a guide or spirit to direct them to passage. Then, with eyes closed, the reader selects a page and then selects a line ( at least this is how I do it; although I am secular, so I work with no entity or deity). From there, the given line can be taken as wisdom, an omen, or a sign. Intuit this. Sometimes, people place the book on its spine and let it fall open (this was traditionally done with the bible, according to some research).

Although there are many approaches to bibliomancy, it is best that you create your own approach. Poems offer the most beautiful and mysterious answers to those questions we hold quiet and deep within us, I believe. In their ability to span the liminal parts of the self — the unsaid, the almost-said, the said-between-the-lines — poems offer great wisdom. Perhaps the spirit of the poet is there to direct you as well.

Poems are little written oceans, in which we dive deep, hungry to reach the bottom. Perhaps there is no bottom and that is the answer. Perhaps it’s the journey that matters.

When you let the book fall open, investigate what a line could mean in the context of your life. What images does it bring to mind? How does it make you feel? What does it force you to think about that perhaps you had not before?

Here, I’ll be doing that for you — for each of the sun signs.

The method: I’ll be opening a poetry book every two weeks and asking for wisdom for each every sign. I will put myself into a receptive, trance-like state (I believe being loose, open, and connected yields the most accurate answers), close my eyes, call out the sign I’m asking about, thumb through the pages of a book, and let my fingers guide me to a line.

It is up to you to reflect the line assigned to your sun sign. Journal about it, meditate on it and listen to the way it reverberates through your mind. Let it stay with you. Write it down and carry it with you.

And at the very least, you’ll discover a new poet.

Our poet is Etel Adnan, and we draw on her book, NIGHT.

Aries

My breathing is a tide. Love doesn’t die.

Taurus

Memory is intelligent. It’s a knowledge seated neighter in the senses, nor the spirit, but in collective memory. It is communal….it helps us rampage through the old self, hang on the certitude that it has to be.

Gemini

What we mean by “God” is that He is night. Reality is night too. From the same night.

Cancer

Words trace their way to the ocean. From the ridge facing this house, signals take off, scaring us, but a large stride, a deep breath, restores tranquility.

Leo

Love creates sand-storms and loosens reality’s building stones. Its feverish energy takes us into the heart of mountains.

Virgo

One day, the sun will not rise at its hour, therefore that won’t be a day. And without a day, there won’t be a night either.

Libra

Are the rockets shooting for the moon killing invisible animals on their way?

Scorpio

Everything I do is memory. Even everything I am.

Sagittarius

Sometimes the sea catches fire.

Capricorn

We create reality by just being. This is also true for the owl who right now is dozing on a branch.

Aquarius

Our mind has a border line with the universe, there, where we promenade, and where tragedy resides.

Pisces

Memory is within us and reaches out, sometimes missing the connection with reality, it's neighbor, its substance.

For more on poetry, divination and magical writing, preorder my forthcoming book, THE MAGICAL WRITING GRIMOIRE.

Lisa Marie Basile is the founding creative director of Luna Luna Magazine--a digital diary of literature and magical living. She is the author of "Light Magic for Dark Times," a modern collection of inspired rituals and daily practices, as well as the forthcoming book, "The Magical Writing Grimoire: Use the Word as Your Wand for Magic, Manifestation & Ritual." She's written for Refinery 29, The New York Times, Self, Chakrubs, Marie Claire, Narratively, Catapult, Sabat Magazine, Healthline, Bust, Hello Giggles, Grimoire Magazine, and more. Lisa Marie has taught writing and ritual workshops at HausWitch in Salem, MA, Manhattanville College, and Pace University. She earned a Masters's degree in Writing from The New School and studied literature and psychology as an undergraduate at Pace University.

MIDSOMMAR’S Hårgalåten and the Ritual of Dance

BY MARY KAY MCBRAYER

*SPOILERS*

I have to confess something about Ari Aster’s new movie Midsommar: I did not identify with or even like Dani until she chose to set her boyfriend on fire. Before you judge me as a vindictive arsonist/murderer, hear me out. Most of my re-alignment with the protagonist is because of the ritual of dance.

I have been a dancer for all of my life—one of my earliest memories is being in a pink leotard at three years old and hearing my instructor say, “If you ever lose your place, just listen to the music. It will tell you where you are.” She meant that we should listen to the counts to situate ourselves in the choreography, but I didn’t take it that way, not even then. There’s something really special about being able to lose yourself in a piece of music, especially when the music is live. It shuts off the rest of your brain and makes you live in your body, and you kind of forget everything that is happening if it isn’t the dance. And when you finish dancing, everything falls in its place.

I remember at one convention I went to, the keynote speaker (Donna Mejia) asked the crowd, “How many of you feel like you are wasting time when you’re dancing? That you should be doing something else?” Nearly everyone raised her hand. “Now, how many of you are only truly happy when you’re dancing?” I did not see a single hand go down.

Sure, it sounds like a lot of existential gibberish if you haven’t experienced it—but let me ask this, more relatable question: have you ever been drunk and lost yourself on the dance floor of the club? (Look at me in the face and tell me you have never suddenly heard the end of a Prince song and realized you were grinding on a stranger in the corner. LOOK ME IN THE EYE. And tell me that.) My point is, when we hear someone is a dancer, we think they are a performer, but that is not necessarily the purpose of dance, not spiritually, and not in Midsommar.

Another confession: most of my dance training is in Middle Eastern dance, which is very different from Swedish dance, but the folk music and dance, and the purposes of it, are not necessarily THAT different. For example, belly dancing originated with women dancing for and with other women. There was no one watching. There was no audience. Everyone danced. It was a form of community. It’s the same community you feel dancing in the kitchen in your pajamas with a couple of close friends. That feeling, the one of being among your friends and doing your hoeish-est dance with a spatula in one hand is the BEST, and it’s what we see in Midsommar with the Hårgalåten. In my experience, that’s when you really start dancing, when you forget that people are watching, listen to the music, and express it in your physicality.

When women dance like that, we don’t care what we look like because no one is supposed to be watching. If they are watching, they don’t stop dancing to do it. And that’s powerful. No one is watching me. Everyone is dancing with me. I am dancing with everyone. No one is watching me, and I don’t care what I look like. (Great performers are the ones who harness this and utilize it onstage, even though there ARE people watching.) You can see the moment that Dani realizes the happiness that come with the May Day dance in Midsommar. It is the first time she smiles in the whole film.

So many of us, too, think that dancing is about the viewer, but it just isn’t. Not on a fundamental level. Sure, dance can be a performance, but that, to me, is not its purpose, and it’s definitely not the purpose of the movie Midsommar’s dance sequence. To me, the purpose of the whole May Day/May Queen dance around the May Pole is to show Dani her true family.

These women embrace her, they let her be a part of their dance community, and that’s so powerful—I’ll never forget the first time a dancer pulled me into the circle of a folk dance. It was magic. I, like Dani, glanced away a couple times to see if anyone was watching.

She wants Christian to be watching, but he isn’t. It seems like she EXPECTS to be sad that he is not paying attention, but then her dancing becomes even more joyful, more spiritual. (You can see this emotional fortitude, though not joy specifically, in spiritual dance rituals around the world, from the Whirling Dervishes in Turkey to the Moribayasa dance in Guinea to the May Day Hårgalåten celebration in the movie Midsommar.)

In the Hårgalåten, the women ARE having fun, though. Though it’s a competition, they are not really competing. Or at least they are not competing with each other.

In the folktale of Hårgalåten, the devil disguised himself as a fiddler and played a tune so compelling that all the women in Hårga danced until they died. In the version that Midsommar tells, the dance ritual is a reenactment of that myth. The women knock each other down because they’re shrooming so hard they run into each other when the music changes. They aren’t mad, though, when they fall. They tumble down, laughing, and roll out of the path of the remaining dancers. The last one standing, one of the villagers says to Dani, is the May Queen.

The May Queen, in the context of the film, has some pretty dark and ominous foreshadowing around her. I assumed, at the first appearance of that archetype, that the May Queen would be sacrificed, and I think that is what the film wants us to assume. That is not, however, what happens, and I was glad of it. (So much of this film is not what I expected it to be, and that is a delight among formulaic horror movies.)

Even the song of the Hårga is told from the first person plural, the “we” of the dancers. They are all invested in the ritual. If one of them wins, they all win. When Dani is the last dancer standing, her new family celebrates with her. They are there for her when she grieves her boyfriend, too.

I love the ending of Midsommar because I feel like Dani really comes into her own; it’s the first time she’s had agency or presented with a choice, in my opinion, throughout the film. As you know, the May Queen is not sacrificed as many of us likely intuited: instead, she’s lifted on a platform and carried to her flower throne. She follows the sounds of another ritual though her now-sisters advise her against it. They go with her anyway. She sees her boyfriend having sex with someone else. She hyperventilates. Her new family is there, with her, breathing with her and comforting her in an empathy so physical it’s uncomfortable to the viewer.

Then, Dani discovers that the May Queen gets to choose the final sacrifice, from between Christian and a member of her new family. She chooses her boyfriend.

Here’s the thing, though: I don’t think she chooses him because he’s “cheating” on her. That ritual, to me, is absolutely a rape, for one. That Christian has a terrible time at the festival is a gross understatement, but the thing to remember is that Christian was shitty way before they came to Sweden, and Dani, like so many women complacent in their relationships, women clinging to a dysfunctional relationship because the rest of their world has crashed, women set adrift from the world, clings to him like a life raft, even though he will not keep her afloat.

During the dance, Dani finds support, love, joy, and that is (in my interpretation of the competition) why she wins. It’s not until she finds that community in Hårga, specifically in the dance with the other women, that she can release the last tether to her unhappiness and set him on fire.

Mary Kay McBrayer is a belly-dancer, horror enthusiast, sideshow lover, and literature professor from south of Atlanta. Her book about America’s first female serial killer is forthcoming from Mango Publishing, and you can hear her analysis (and jokes) about scary movies on her blog and the podcast she co-founded, Everything Trying to Kill You.

She can be reached at mary.kay.mcbrayer@gmail.com.

=

At The Intersection of Chronic Illness & Ritual

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

Long before I knew I had a chronic, degenerative illness (Ankylosing Spondylitis, a disease that fuses your vertebrae and joints together), I lived with fatigue and widespread pain and chronic eye inflammation (which, of course, led to reduced vision on top of cataracts from steroid treatment).

It took a decade (with on and off insurance) to convince doctors that I wasn't inventing an illness, that my eyes weren't red from "contact irritation," that my pain wasn't from getting older, that my tiredness wasn't from binge-drinking or staying out late dancing. (To be fair, I did all of those things, but the heaviness in my bones was its own strange animal, an animal that I lugged along with me while all of my friends bounced back after a night out).

Many people with chronic illness (especially with autoimmune diseases) have ventured down the same winding path--medical neglect or disbelief, lack of resources, lack of knowledge in the medical community, lack of diagnoses, and a lack of support.

If you are the only person you know with an autoimmune disease or a chronic illness (or, really, any type of lasting body trauma), you know how isolating and fear-inducing it can be. Do you really know your body if your body is betraying you? Do you have a handle on your own future? Are you somehow no longer the same? Can you get the help you need?

My body was two people. A young girl, and a bag of blood, going on a bender, following no directions, attacking herself. I was lost to my selves.

When I finally convinced doctors to test me (for HLA-B27 antigen, plus an MRI to detect fusion), the diagnosis was an existential blow. I suspected the disease, of course--as my father has it--but knowing that I'd never, ever be cured felt like a sentence to me. For a year, I wallowed. I felt self-pity, I felt out of control, and I was on the edge of constant sadness. I felt lame. I felt silly. Here I was in my early thirties being told I might be fused together later on, my body a prison, my body no longer mine, but a shackle keeping some version of me tucked down deep inside.

I had always turned to ritual throughout life, especially when times got rough. Ritual is there for these times. It establishes a sense of order, it makes space specifically for the self, and it encourages focus, intention, and growth.

I used ritual to help me escape those constant thoughts of worry, anxiety, self-doubt, exhaustion, and fear. I used ritual to establish routine and self-care and self-empowerment. Through lighting candles each week night as a way to make rest time to decorating an altar in honor of myself and my body, I became an advocate for myself. There were many: bathing in lavender to intentionally create a sense of fluidity, journaling nightly through pain (using that painful energy to focus and transmit change and manifestation). If it all sounds woo-woo, consider this: anything you do for yourself is a ritual already. Anything you put your mind to is more likely to happen. Any time you carve out for yourself is sacred. It's an act of warfare against chaos and self-loss. It's a reclamation, a creation, a magical hour.

Ritual helped me back to myself: I felt stronger, more determined to make time for myself, more connected to the simple things that made life fulfilling and beautiful (rest, a walk in nature, time to write, creativity). The disease no longer controlled me; instead, it was a part of me, as a sad friend in need of love and time and cooperation. I was a vessel for opportunity, not despair.

A year after my diagnosis, I also went on to write a book, Light Magic for Dark Times--which is a collection of rituals and practices for hard times. I even included a portion on body and identity, and chronic illness.

I will be leading a workshop on chronic illness and ritual at MNDFL Meditation in NYC on July 21. I hope you will come, as it will be an open, safe space. We will discuss chronic illness, meditate, and map strategies for self-care and self-empowerment. All are welcome!

About the event

Welcome to Strong Women Project's first women's wellness workshop!

We're connecting with MNDFL in the West Village to provide free workshops to focus on our wellness. Our first workshop is led by Lisa Marie Basile. Darley Stewart, SWP Founder and Curator, will also speak about chronic illness in the context of recent findings. We'll also do some light meditation and stretching to kick off the workshop.

Lisa Marie Basile will discuss what it means to establish ritual as a way of encountering one's chronic illness or other body-mind related traumas. Ritual might mean bookending one's day with someone positive and encouraging but it can also mean going deep and dark and peering into the abyss of self to confront the pain/shame/etc of chronic illness. You can expect to feel like you are part of a loving community and to come away with a set of tools that can help you when you feel overwhelmed or lost, or are just looking to transmorph your experience into art or inspiration. It's a balance of light and dark. Lisa Marie Basile is the author of "Light Magic for Dark Times," a modern guide of rituals and daily practices for inspired living.