Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of several collections, including Marys of the Sea, #Survivor, (2020, The Operating System), Killer Bob: A Love Story (2021, Vegetarian Alcoholic Press), and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Them, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente / FB: joannacvalente

Read MorePhoto: Joanna C. Valente

Writing, Magic & Tarot: Pairing the Major Arcana to Poetry

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of several collections, including Marys of the Sea, #Survivor, (2020, The Operating System), Killer Bob: A Love Story (2021, Vegetarian Alcoholic Press), and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Them, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente / FB: joannacvalente

Read MoreSummer Poem: Court Castaños

Magic Breathing

BY COURT CASTAÑOS

We didn’t have fireflies

flickering summer’s arrival song

in old jam and jelly jars, and I wish

I’d seen them rise from the tall grass

mistaken them for sprites, magic

breathing. We were washed

in the orange glow of the street

lights higher than we could ever imagine

climbing with our rough hands and

thick, summer feet. By June

you could crack an egg on the searing

tar of your road and watch it blossom

sunny side up until the slap

of burnt yolk sent you running

to the cool relief under

the maple tree, where the sun

couldn’t find you and the light

was mashed to cool green

like grass that’s been bruised

and tugged loose by dancing feet

in holy sprinkler water.

As a kid I could chant all

the priest’s calls and responses, sign

the cross over my small body and

say Grace five-times-fast,

but in the young nucleus of my soul

I knew the real power was in the count

to thirty on a moonless night while the

street exhales it’s last fiery breath.

My body in flight to the cavern

in the arms of my orange tree

where my heart would howl

in ecstasy as I praised the dim glow

of the street lights and the holy

sanctity of bare feet running

in a pack of wild kids, playing

hide and seek in the dark.

Donate: The poet requests that donations be sent to RAICE’s LEAF Fund. The LEAF fund ensures that children coming to this country can receive quality legal representation both in detention centers and once they are released. In 2018, our specially-trained team provided ongoing legal counsel to 400 children, and more than 4,500 children received training to help them understand their rights here in the United States. You can donate via this link.

Court Castaños has work currently published in The Nasiona and the San Joaquin Review. New poems forthcoming in Boudin, of The McNeese Review. Castaños grew up adventuring along the Kings River in the San Joaquin Valley and now resides in Santa Cruz, California.

Photo: Joanna C. Valente

The Queering of Time and Bodies through AI

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of several collections, including Marys of the Sea, #Survivor, (2020, The Operating System), Killer Bob: A Love Story (2021, Vegetarian Alcoholic Press), and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Them, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, and elsewhere. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente / FB: joannacvalente

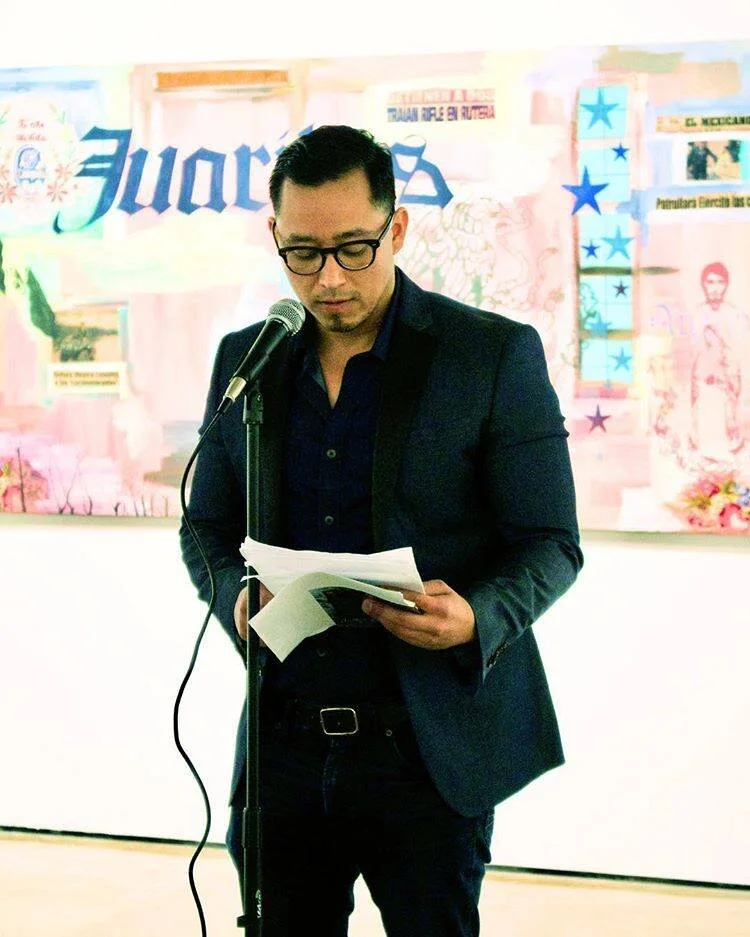

Read MoreImage via Octavio Quintanilla

' Frontera and Texto ' : An Interview with Writer Octavio Quintanilla

…Frontextos has become ritual, meditation, prayer. Action is the mantra.

Read MoreWhat if the earth is asking us to be still?

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

Tune in with me.

I think about the people who will populate our future, and I ask the sky what they will see, what they will be told — through our actions and words and hunger. Will we become their ancient gods, whose lessons are bleak and hellish? Will they see how hard many of us tried and how we hoped?

Will our mythos be of hyper-consumerism, racism, lovers who are not allowed to love, bodies put into categories, plastic, the poisoned fruit, the unbearable dullness of constant performance, the addiction to the avatar, the plutocracy, the oceans crying into themselves, the sound of the air cracking against the ozone? Will all of our wounds still be present?

When I think of the people of the ancient worlds — and their gods and their cultures and their arts — I wonder what they would have wanted us to know?

Did they hope to impart a message of beauty, art, and nature? Of storytelling and culture?

Did they think we would destroy one another and the earth they danced upon in worship?

What happens to everything when we sit in the sea? Do we become a primal beautiful thing?

There is a presence that is being asked of us. Do we hear its sound? Are we the people who tolerate abuse? Are we the zombies of decadence, the digital void that consumes and hungers through screens? What if we were embodied for a day? Would we hear the great chambers of our heart, and the hearts of strangers, and the vines and sea beings we came from?

There is a constant scrolling and feeding. And it’s because we are hurting. We are disconnected. We are oppressed. We are poor. We are sick. We are not seen by society. We feel lonely, a loneliness perpetuated by hyper-connection.

How else do we live without turning to the void, which provides us beautiful and loud things to buy and be and shape ourselves into?

How do we live without abusing our neighbor, without stomping on their chest?

What if we could remember ourselves? How miraculous we are? Would we remember to be generous, to heal, to say hello? What would it look like if we all stopped pushing for a moment? What if we let the wind move us?

Positano

I feel sometimes I am a ghost. Liminal, floating through the world, eating the world around me — media and fashion and ideas that are not my own, not aligned with my values or my traumas or my soul.

I am out of time with my own soul. I am in 2020, but my heart is in the ocean eternal. I want wind and shorelines. I want fairness and justice. I want to experience beauty without the billboards looming. I want to read a book in the sunlight, and see my neighbor have the same opportunity.

But my neighbors — and your neighbors — are dying, are being murdered, and our ecosystems are gasping in our wake.

La Masseria Farm Experience

There are days that are so beautiful, so soft and real, that I have hope. These are holy days.

In Campania Italy, I have a holy day. I sit in a small stone pool. I think of the drive through the mountains from Napoli, where Pompeii stands, its breath held, looming over its land. How it preserved the stories of its people. I think always of what is preserved, what is lost.

But in the little pool, I am alone. The bed and breakfast is quiet. Tourists are out at Capri or Amalfi, the staff are napping during siesta, making pesto, somewhere else paying bills, talking on phones. I hear the hum of a generator, street dogs barking, the starlings that fly over me back and forth, definitely flirting.

I whistle and they zip over my head. We are in conversation, I know it. The earth wants me to know it sees me, wants me to see it. I am here and nowhere else. I am completely alive. I am made for this moment; we all are.

And after the late dinners of fried fish, I walk back to my room, alone. I am greeted again by the tiny birds who flutter in and out of the domed entrance, cherubs painted across the ceiling. I think of time and nature, and its concurrent obliviousness and suffering. I think of my privilege, and what I can do to preserve these stunning things.

I think of my body withstanding 100-degree heat. How I talk to the creatures in some liminal language of love. I think of how we could all be good to one another, so good that we could all have holy days.

I think of my flesh as the wine of this land. I feel the Mediterranean and the Tyrrhenian Seas in the palms of my hands. I am so alive and grateful and awake at the altar of these moments I cry for the nostalgia that hasn’t come yet, that I know I will feel. That I do feel. I am both past and present. But mostly, I am now.

I walk up the road to a farm and am greeted by a family whose hands have nurtured and translated the earth for centuries. They climb the trees, show us the olives falling. We see the farm cats idle in their sunlight, their fur dotted in soil. They are languid in pleasure and warmth.

I lose myself in the lemon trees, smell their peels; I am blessed. I step into the cool room where they keep the jugs of Montepulciano and cured meats. A cry in ecstasy is somewhere within me.

After a long day of pasta made by hand and more wine and strangers inviting me to their table and then limoncello, I walk home to my room. I am drunk on the connection. I film the walk, then stop. I do not want to capture everything; some things just exist between me and the earth. I won’t share.

La Masseria Farm Experience

My room is called Parthenope. It is etched into the wooden door. When I open the door, that is the threshold, the portal. Parthenope is a siren who lives on the coast of Naples. I imagine her body clinging to the continental shelf, her hair entwined in shell. They say she threw herself into the sea when she couldn’t please Odysseus with her siren song. Or maybe a centaur fell in love with Parthenope, only to enrage Jupiter, who turned her into Naples. The centaur became Vesuvius, and now they are forever linked — by both love and rage. Is that not humanity?

She became Naples. She became forever. Her essence is water, is earth, is the mythology of what happens when people are cruel and jealous and oppressive. Is this the message the sirens are singing? To be tolerant? To normalize cruelty? To fill the void with empty media, with images without stories?

Lubra Casa

There is always something that could destroy us, could rid us of this existence. A virus, a volcano, our own hands.

We are temporary, so quick and light and flimsy. We are but a stitch of fabric. A dream within a dream of that fabric. And yet. Here we are, becoming the ancients, carving out a way toward the future. We visit volcanos. We mythologize the earth. We drink wine and capture beauty. But then we turn our backs — on the proverbial garden, on one another, on our own bodies.

What if the earth is asking us to be better? To be still? What pose would we hold? What shape could let all the light in?

LISA MARIE BASILE is the founding creative director of Luna Luna Magazine, a popular magazine & digital community focused on literature, magical living, and identity. She is the author of several books of poetry, as well as Light Magic for Dark Times, a modern collection of inspired rituals and daily practices, as well as The Magical Writing Grimoire: Use the Word as Your Wand for Magic, Manifestation & Ritual. She's written for or been featured in The New York Times, Refinery 29, Self, Chakrubs, Marie Claire, Narratively, Catapult, Sabat Magazine, Bust, HelloGiggles, Best American Experimental Writing, Best American Poetry, Grimoire Magazine, and more. She's an editor at the poetry site Little Infinite as well as the co-host of Astrolushes, a podcast that conversationally explores astrology, ritual, pop culture, and literature. Lisa Marie has taught writing and ritual workshops at HausWitch in Salem, MA, Manhattanville College, and Pace University. She is also a chronic illness advocate, keeping columns at several chronic illness patient websites. She earned a Masters's degree in Writing from The New School and studied literature and psychology as an undergraduate at Pace University. You can follow her at @lisamariebasile and @Ritual_Poetica.

Body on Pause: Miscarrying During A Pandemic

BY PATRICIA GRISAFI

I decide Fiona Apple’s Fetch the Bolt Cutters will be the soundtrack to this miscarriage. As I get my things together—mask, extra mask, gloves, bottle of hand sanitizer, plastic baggie stuffed with wipes—I wonder if my album choice is cliché. Almost every critic has loved Fetch the Bolt Cutters, gushing about how it feels made for a quarantine.

The procedure to remove the dead fetus from my body is supposed to be about ten minutes long. I get on the M15 bus after a fifteen-minute walk and survey the passengers sitting quiet and masked in their seats like a de Chirico painting. Then I make a playlist called “Miscarriage.” The songs are “Newspaper,” “Under the Table,” and “For Her,” all songs about patriarchal abuse and trauma.

This is my fourth miscarriage—sixth if you count chemical pregnancies, which the doctors do—but I’ve never had a vacuum aspiration before. All my procedures have been D&Cs under sedation. However, with New York City hospitals full of COVID-19 patients, my best bet is an in-office procedure. I am disappointed I won’t be knocked out.

In the waiting room, three heavily pregnant women fuss with their phones. I think of my two-year-old son at home, getting ready for nap-time. My husband sends me updates on the situation: “he’s chattering too much,” “oh, he’s quiet now.” I miss my husband’s presence in that room, thinking of past surgeries when I emerged from sedation with a newly hollowed uterus to his embrace. But he’s not allowed to be here—patients must come alone. No husband and toddler in tow during quarantine.

I miss so many things, frivolous things. Sharing a morning muffin with my son at the dog park. Sipping margaritas with a chili salt rim on an outside patio. Wandering into Rite Aid for no reason. Perusing the shelves at the local bookstore with a cup of coffee. Family walks that don’t feel limned with disquiet.

The procedure will happen while I am laying down, my feet in the stirrups. Later, a lab will test the “materials of conception” from this pregnancy for chromosomal abnormalities. I won’t have to see what comes out of me—not like there will be much at eight weeks. “Embryonic demise” probably occurred at around week six or seven after the grim ultrasound when the doctor reported a feeble heartbeat and a too-tiny fetal measurement. I’ve been fixating on the fetus slowly dying inside me and then on my body as harbor for its corpse.

How can you not think about death during a pandemic? Since the day our family began sheltering in place, I had been carrying the small hope of that baby. On March 7th, I was inseminated in one of the anonymous rooms at Weil Cornell, my husband holding my hand as they threaded the catheter in. Afterwards, he played a heavy metal version of “Toss a Coin to Your Witcher” on his phone, and we laughed.

My first son was conceived this way—with the help of science after infertility flooded my body with doubt about my ability to have children. I dutifully went every other day to have my blood taken and my vagina probed. Between my first struggle to keep a pregnancy viable and all the subsequent losses, I found myself thinking about my uselessness as a woman in a world without medical intervention.

“In ancient Sicily, they’d have thrown me in the prickly pear bushes, maybe burned me. Maybe I’d be the village witch, like Strega Nona—except hated,” I had said, thinking about how much family meant to my genealogical constitution. A woman who couldn’t have children was a problem. A curse. She had done something to deserve infertility. Send her away.

My paternal grandmother did not want biological children, so deep was her fear of dying during childbirth. She even found a child to adopt in New Paltz, where my grandfather and she had a one room cabin for summers. My grandfather wanted his own child, and I imagine him saying no to the adoption and then forcing himself inside her and making my father.

This is not history, not fact. It’s my brain winding around the possible ways my family made a family. My grandmother didn’t have her only child until after eleven years of marriage—unusual for Italian Catholics during the 1930s. My mother tried to get pregnant for eleven years, submitting to every experimental procedure in the ‘70s and ‘80s until I was born—also an only child.

When my mother and I fight now, I think about what she put her body through for the slim chance of a child. Is reproductive trauma something the women in my family share, a story they’ve only been able to tell through their live births, a story otherwise hidden in the deepest parts of their selves? What kind of woman volunteers her body for this kind of repeat torture?

I’m ushered into the procedure room. The doctor gives me a Motrin. I’ve brought my own Klonopin because I’ve been on them forever. I wonder if I should take two instead of one. I take one.

The moment my feet hit the stirrups, I press “play.”

“Are you okay,” the doctor asks me.

“Yes,” I say, because I am a good patient but also because I know this must happen.

The doctor and her assistant try to shove metal accoutrements into my vagina with delicacy. It’s never pleasant, the speculum. Then there are the tubes. Then there is the anesthetic, which makes me feel high and chatty for about three minutes. I want to babble on and on about my child, to remind them I’m a mother and not a collection of losses.

Fiona Apple’s frenetic warble pierces me as they start the procedure. I try to focus on that voice, a voice that arches and peaks and trembles and breaks. A voice that is fragile but strong.

As the pain begins, so does “For Her,” and I think about the man who pinned me down and came on my face while I screamed and cried. I can’t help it. This asshole hops onto my nerves at unexpected times. I dig my nails into the fleshy cradle of my hands as Fiona sings, “Good morning, good morning, you raped me in the same bed your daughter was born in.”

The doctor finishes up. She’s been telling me all along how good I am doing.

“Rest for as long as you want,” she says as the last instrument is removed.

I haven’t shut off the playlist. Liz Phair’s “Fuck and Run” randomly comes on, and I feel like laughing and crying at the same time.

It takes twenty minutes to hail a cab. Finally, one stops. It is a van with a plexiglass barrier window, and I feel grateful. I open the window with my gloved hand. They’re garden gloves, the kind I use to repot the easy plants I keep killing in my apartment. I hear the whipping of wind on the FDR, the thrum of pavement under the wheels.

My son is asleep when I quietly step into the apartment. My husband holds me tightly.

“I’m so tired,” I tell him, like a child who wants to be taken care of. “Can you tuck me into bed?”

Whenever I have a miscarriage, I feel like a failure. The eggs too old? The lining of my uterus not thick enough? The questions are endless. The disappointment hangs like a heavy curtain.

During a pandemic, it’s worse. There’s an irritating urgency and a paralyzing fear about when we can start to try and expand our family again. The fertility clinic will eventually reopen, but when will the world? When will it be safe to travel for blood-taking and hormone-monitoring? For poached eggs and harissa? For play dates and bang trims?

In the meantime, I make cocktails with lemon and whiskey. I draw owls for my son. I shave my armpits but not my legs. I stare out the window. When my husband and I begin work, I put on Peppa Pig and plop my child into his high chair.

But my professional life suffers for the love of being around my son. I stop to pet him, fetch more goldfish crackers, kiss his head. And then I want to sleep, like the protagonist of Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation. Sleep right through the plague, sleep through the fear, sleep through future fertility treatments. Wake up like Giambattista’s Basile’s Italian Sleeping Beauty, a surprise baby suckling at her breast. Forget that Prince Charming raped and impregnated her while she was unconscious.

Pregnancy destabilizes your sense of self. It changes you. In some cases, fetal DNA remains in our bodies long after a child is born. This phenomenon is called microchimerism after the mythological creature composed of many parts, usually depicted as a lion with the head of a goat and a tail trailing off to a snake’s head. If a pregnant woman is not a chimera, I don’t know what is.

When I was younger and learned about viruses for the first time in science class, I was terrified. There is still something about a virus that frightens me. I’ve had the chicken pox, I’ve had the flu. The first time I had a wart on my finger, I cried for days. The idea that viruses never really leave, that they exist inside of us in various states of dormancy or activity forever, made me afraid of my body’s uncontrollability.

I think about bodies constantly now—permeable, malleable, capable at times and utterly useless at others. Sacks heaving in and out. A contemptible, fickle uterus. Contracting or relaxing the pelvis as fetal tissue is aspirated. Mouths releasing clouds of germs. The touch of my child’s hand as I guide him on makeshift Pikler triangle made from the side of his crib propped up against the couch because we can’t go to the playground anymore.

“Mommy, hold hand, please,” he says extending his chubby little paw, attempting to make his way down the ladder.

“I’ve got you,” I say.

We soldier on.

The last song on Fetch the Bolt Cutters is called “On I Go.” With its repetitive lyrics about repetition set against atonal cacophony, it feels like a woman scraping at the walls of her mind, her body, the apartment she’s trapped in while a pandemic rages outside.

"On I go, not toward or away

Up until now it was day, next day

Up until now in a rush to prove

But now I only move to move.”

It’s not a pleasant listen. Maybe it feels too sharp right now, prodding at a wound. But I understand what’s at stake, the overwhelming desperation to have agency over life only to find the attempt futile and give up. Or perhaps it’s a kind of triumph—reclaiming the conditions of one’s journey.

The day after my procedure, I walk gingerly between the bedroom to lay down in silence and the living room to lay down in chaos. This is the choice I can make. There is no real movement, no escape except for short, nerve-wracking walks on the East River that are actually practices in weaving and swerving. Time feels suspended—our family on pause. My body on pause. My life on pause.

Right now, I only move to move.

Patricia Grisafi, Ph.D., is a freelance writer and editor. She writes about mental health, popular culture, film and literature, gender, and parenting. Her work has been featured in The Guardian, LARB, Salon, VICE, Bustle, Catapult, Narratively, The Rumpus, Bitch, SELF, Ravishly, Luna Luna, and elsewhere. She lives in New York City with her husband, son, and two rescued pit bulls. She is passionate about horror movies and animal rescue.

Poetry by Lauren Saxon

BY LAUREN SAXON

22

after Fatima Asghar’s Partition

I am 22 & have not been hugged in a long time.

I am considering the English language—

how it gave us both the word hug & the word embrace.

do not mistake them for one.

I love her. I love her.

I will always be this way.

my mother, I fear, will not attend my wedding.

my father is selling the house—

it was to be kept for legitimate grandchildren only.

I am no stranger to my parent’s arms.

I still call my father’s cologne, home.

I am proud to have my mother’s smile.

still

my parents hug

only the parts of me that they can embrace.

I am certain my body would feel differently.

I am 22 & have not been hugged in a long time.

I watch my parents greet me from a distance.

it is clear that they have missed me.

when my mother wraps her arms around me,

I cannot feel them.

I am standing behind myself,

keeping two white gowns from touching the ground.

when my father wraps his arms around me,

he does so on borrowed land.

it is possible to be hugged & not embraced.

the proof is right here in my breath.

I will always be this way.

SUPPORT LAUREN SAXON BY DONATING VIA VENMO: @Lsax_235

Lauren Saxon is a 22 year old poet and mechanical engineer from Cincinnati Ohio. She attends Vanderbilt University, and relies on poetry when elections, church shootings, and police brutality leaves her speechless. Lauren's work is featured or forthcoming in Flypaper Magazine, Empty Mirror, Homology Lit, Nimrod International Journal and more. She is on staff at Gigantic Sequins, Assistant Editor of Glass: A Journal of Poetry and spends way too much time on twitter (@Lsax_235).

Summer Poetry: Courtney Cook

BY COURTNEY COOK

We Skipped Spring this Year

Suddenly, the blare of August, waves above

the asphalt. There’s a ghost hanging around

my bedroom leaving hair on my pillow. I notice:

a second toothbrush beside the sink, fingerprint

bruises on my thighs too big to be my own,

a condom in the trash can. I can’t finish a cigarette,

try to pass them to no one but air. Where’s

the other mouth? To erase a memory as it unfolds;

to desire that. Isn’t it strange, the way the world

continues to expand after an end?

Summer

Cicadas burst under my bicycle tires pressed into stone

they scream high-pitched lobster boiling they cover

the walkway die beside the orange blossoms petal softness

an offering buzzing on the ground like fighting brothers

their exoskeletons still clinging to bark summer transparent

sliding over the world everything sticky and sweet fleeting

the cicadas who emerged from hibernation calculated days to fuck

and gorge themselves before morning brisk or rubber

comes to kill them to end something before it really began

a return to a world without them, the waiting again.

Support Courtney Cook by donating via Venmo: @courtney-cook.

Courtney Cook is an MFA candidate at the University of California, Riverside, and a graduate of the University of Michigan. An essayist, poet, and illustrator, Courtney's work has been seen in The Rumpus, Hobart, Lunch Ticket, Split Lip Magazine, Wax Nine, and Maudlin House, among others. Her illustrated memoir, THE WAY SHE FEELS, is forthcoming from Tin House Books in summer 2021. When not creating, Courtney enjoys napping with her senior cat, Bertie.

Quarantine by Leslie Contreras Schwartz

BY LESLIE CONTRERAS SCHWARTZ

Quarantine

The lights in the bedroom flickered off and on. I lay in our bed listening to a heavy thumping coming from somewhere, quickening. In a half-dream, I created the idea of walking to the door and shouting, Who’s doing that? Even the thought of it was tiring, and I rolled over with eyes half-closed, lucid enough to be afraid to sleep but longing for it with the same urgency I longed to take a deep breathe without pain, or to be able to sit up with my lungs feeling crushed. I tried to fill my thoughts without something other than the every second of half-breathing, the crushing and stupor.

Was the sound growing near? Was it a foot banging a door, my daughter running circles in the living room, feet pounding in a rhythmic pattern? Was it the neighbor at some task again that required loud repetitive pounding and screeching? The questions were something to latch onto in my mind. I entertained them.

A slit of light broke from the bedroom door and my son crawled in beside me, wrapping his small limbs around mine underneath the coat of blankets. He was whispering but I could not hear because of the thumping. Who is doing that, I said. I slept.

My husband woke me to feed me soup, water from a straw. I sat up in bed, the room bluing. Our five-year-old was jumping on the bed, adding a beat to the drumming that started again when I opened my eyes (though I was sure I heard it in my sleep). It had been weeks since I’d left either the bed, or the couch, laying, blinking, and when awake, staring through the window, at a wall, at one of the children’s faces. Breath came as if through a tiny sieve, which I gulped in small pockets. You’re here, the doctor said this morning on the phone. Be grateful. So the air like fish eggs, like the meager rationing in the form of pills. Sucking, coughing, my chest strained and ready to snap. Nebulizer hush and burr. Inhaler sip. Eight more times. Times seven. Again. Times sixty days.

The world shimmered in blue, the faces of my son, my husband and our girls, cast in that same blue. One morning or one night, or the next day, or the night that was yesterday and before, tomorrow, I dreamt of running at full speed down our street, past the school, toward the bayou ten blocks away. The banks were filling with rain, ready to break over the edge of the concrete embankment, and I ran so hard every part of me ached and knew that this feeling, familiar, happened yesterday, today, and tomorrow. I woke up wheezing and choking. The thumping in my ears, my own heart racing, like I was running, every second running.

At the insistence of my husband, I sat outside wrapped in a blanket and feeling shorn. I watched my children play in the front yard while the light flickered through the leaves of the tree on the lawn. Underneath the world—or was it beside it, along it, between it? (There was no relative space to pin it)—I saw the pulsing of blue, an under-color to the kaleidoscope of reality’s rough imagery—my son’s kid sneakers of black and red and white, flashing lights when he jumped, my eight year old’s plastic sandals, both of them dangling off the edge of a spider swing, their small hands flayed out and waving. The laughter, her sigh. Underneath it all was this color, not an earthly blue, blue of ocean, precious stone or gem cut into rock, a sky flanking a horizon. No. This blue which was not blue was the color of sacred, deep, with a center to it, blood of childbirth, the whitened lips of the dead, the infant’s purple wail—all of it mixed together, long and unraveling, a cruel silence with a terrifying bell inside.

I rested my head back on the chair and stared at the sky that was no longer the sky. I blinked and felt close to that color—this underwater, the blue eggs, blue veins on an infant’s foot, the black feather of a blue jay that feigned blue, the blue mouth of a glacier. Was this what ran parallel and twinned to our lives, a universe linked with a battered rope to this one, where I had died, and hanging by a thread to the universe where I lived. The giant bell in its cruel silence behind the blue, and my rollercoaster heartbeat readying me for the terrifying drop to the ground. I longed to hear the bell. I would not share it, only save it inside my body, and never, even to my worst enemies, tell anyone the sound it made that killed small parts all at once with a blow. I opened my eyes, feeling heavy. I had already heard the bell. I had already imagined my children without me. I sat feeling the holes of it, growing cold. Light overhead grew brighter until wind threw the branches together, a dark shadow enveloping our family. Spin faster, I said to my children. Do it again.

SUPPORT LESLIE CONTRERAS SCHWARTZ BY DONATING VIA VENMO: @Leslie-ContrerasSchwartz

Leslie Contreras Schwartz is the author of Who Speaks for Us Here (Skull + Wind Press, 2020), and the collections Nightbloom & Cenote and Fuego (St. Julian Press, 2016, 2014). Her work has appeared in Gulf Coast, Missouri Review, Iowa Review, Pleiades, among other publications. She is the Houston Poet Laureate.

Poetry by Elizabeth Theriot

BY ELIZABETH THERIOT

The Fates ask where the Underworld went with its lake of ghosts

Summer left a grave of black cherry pits and twisted stems. Autumn waits on the sidewalk, down the stairs, to burn leaves and smudge the city in its smoke. We’ve sat in this between blinking sleep from our eye, collecting all the seasons’ fraying ends.

Banishment: when the soul wants to dig itself up.

Someone said not to write soul in a poem. Someone told us catastrophizing was the right verb but catastrophe is grey funk beneath our nails, a catastrophe on the scalp, caking pores, a layer of grit. We drink Windex until our eye sees clean.

Exile: where the body chooses to bury itself.

Circling the Dog-Moon Heroine

(a story in fortunes)

Throned in leather Hierophant waits

two fingers double-

pillared. Speaks

binaric code like,

this is what my centuries have created. It is good.

It’s real good.

Hierophant wipes BBQ

palms on the couch

waits for someone else

to clean it up.

Someone always does, who likes the couch,

cares if it looks pretty.

Hierophant waves

fish-spine gold

and cleanpicked

(fondant crown a-dripping)

His eyes Abrahamic, like

not my fault

sad shrug. Keys crossed on the carpet.

All the while ma folds

laundry, and your ma too.

//

So here goes the fat

yellow moon shedding skin at the crossroads :

dogs shocked by

sharp girly moon,

tails bristle like

terrified of dew, plush ears

underfed and curling. Ma curls

your hair with a hot wand.

Sunflowers fat-bubble

along the wall. Whose blood

on the rocks? Ma straightens

your hair

with an oiled spatula

and the cinderblock towers

go sizzle in-

between.

After all the hullabaloo

you’re a baby again, Age of Aquarius baby

crying, little Bacchus baby

the deferential horse

in globs of playdough sun,

baby body WHEE between horse-blades,

jazz-hands like

a birthday gift, red feather

in your jelly ringlets

and Ma

with a quick wrist-snap

folds laundry, unfolds laundry to make the beds.

Muse Epistle

Scars below my skin are proof

you were gestated—raised, fed—

divinatory cradle—grown in minutes,

warm between my painted toes.

And the petals opened:

Water empty like bitten

skin around nails, my palms

stretched into pollen and flame—

candle pyre altar spelled the same.

You should have warned me

when I loved

as fetish-tucked-in-drawer;

your long gone infancy;

eyes dripping

in caverns you devour

songbirds

then crawl into bed, unsocket

my limbs and dab glue

as ointment—

slow burn, elegy, I

have let it happen.

Elizabeth Theriot is a queer southern writer with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. She earned her MFA from The University of Alabama and is writing a memoir about disability and desire. She is a Zoeglossia Fellow, and a teaching fellow with the nonprofit Desert Island Supply Company. You can find her work in Yemassee, Barely South Review, Winter Tangerine, Ghost Proposal, Vagabond City, A VELVET GIANT, Tinderbox, and others. She lives in Birmingham, AL.

Poetry by A. Martine

BY A. MARTINE

grapevine gossip

from time to time i look up a man i almost

dated to test my intuition’s mettle

the addendums i append to my search

varying only in their extremity

firstlast + jail

+ serial killer

+ murder

can’t help but probe, set stiff set stiff

for the soft spot in my duodenum where

my foresight rests, and try to prove

it wrong, and my other senses too

that my bloodhound ears didn’t register

what they think they registered while he

was threading me metal spools of sparkling

ovations, so sharp they gashed when handled

all that talk of redemption, all that

tell me what scares you, for i am scared too

trifectas the two-pronged truth, my beast

recognizes in him a wholly deeper beast

softspot screams the very first song i, newborn

woman, heard offered me: runrunrun for the hills

can’t help but silence it, set stiff set stiff

or maybe it’s admission to that club i’m

rescinding, the one that standardizes

ambidextrous horror — we’ve all dated a creep —

until it, too, internalized, feels like a dinky

pinch, duodenum subdued to ruination

from time to time i google a man i almost dated

and am stunned to learn he hasn’t killed anyone

yet

and though i am momentarily comforted, assurance in

others’ inner workings set stiff set stiff

my softspot-foresight promises, wasn't all in your head, you just wait, you just wait.

Hecate's Wheel

Convinced it tasted of soot and salt,

time and again I tried to bite off

the ink-blot stain on my tongue,

responsible, surely, for tinging

everything I drank with its essence.

That is, until I understood. In Senegal:

we inkblot tongues are soothsayers.

Anything we say comes supposably true,

contrapasso dispelled indiscriminately.

Should a wordsmith like me be thirsting for

that kind of omnipotence? I hope

to be one of the good, really good ones;

but buzzing bees in my elastic throat, I

know I go both way with words, have

only mouthfuls of cursepells to offer.

To blazes with intent: I thought I wanted love

to feel like something belonged to me.

Why did I say: i know when my flaming

lifeblood hits the floor and bursts

outward like ember petals, I’ll be

incandescent, the epicenter of disaster,

too fierce for love, too good for love.

When said love deserted me, I spent a violent

year supine on the coal floor beseeching

Take it back, I take it back I take it back.

I think I am one of the good, really good souls,

but it never occurs to me to say good, and to

wish for good. I cannot plagiarize what I’ve

never known. At the suggestion of pandemonium,

my inkblot tongue comes alive.

I could kill this liar with a prayer.

Even when my malice maimed the cruelest

boy I knew, omnipotence like the

resounding crack of a whip—

Again!

Again!

I was Doubting Thomas, if he were a woman who’d been

taught and taught to disbelieve. A maelstrom

thrashed in my palms, and I still underestimated

how fearsome, how formidable

I could be.

SUPPORT A. MARTINE BY DONATING: paypal.me/martinathiam

A. Martine is a trilingual writer, musician and artist of color who goes where the waves take her. She might have been a kraken in a past life. She's an Assistant Editor at Reckoning Press and a co-Editor-in-Chief and Producer of The Nasiona. Her collection AT SEA was shortlisted for the 2019 Kingdoms in the Wild Poetry Prize. Some words found or forthcoming in: Déraciné, The Rumpus, Moonchild Magazine, Marias at Sampaguitas, Bright Wall/Dark Room, Pussy Magic, South Broadway Ghost Society, Gone Lawn, Boston Accent Lit, Anti-Heroin Chic, Figure 1, Tenderness Lit. @Maelllstrom/www.amartine.com. is a trilingual writer, musician and artist of color who goes where the waves take her. She might have been a kraken in a past life. She's an Assistant Editor at Reckoning Press and a co-Editor-in-Chief and Producer of The Nasiona. Her collection AT SEA was shortlisted for the 2019 Kingdoms in the Wild Poetry Prize. Some words found or forthcoming in: Déraciné, The Rumpus, Moonchild Magazine, Marias at Sampaguitas, Bright Wall/Dark Room, Pussy Magic, South Broadway Ghost Society, Gone Lawn, Boston Accent Lit, Anti-Heroin Chic, Figure 1, Tenderness Lit. @Maelllstrom/www.amartine.com.

Summer Poetry: Max Kennedy

Paramount

you’re a folk fiddle

in a hound’s-tooth coat

you stand eaten

in the hot wind

tumbleweeds cling to your

last words

drain as i cut

the melted rope

holding us together

you always read

faster than you wrote

sang like your mother

danced wildly like your father

in the summertime

fell like me

you talked the big talk

as if

walking weren’t a weapon

where you’ll end up next

cross county lines,

scream double-time—

a paramount decision

the water’s too deep in the well

to crawl back up the side

snakes lay in your bed

where i left my good ring—

lucky for you

i have plenty of jewels

sitting around

waiting to be used

Last year in July

It’s almost July now

Somewhere close by,

Windows shift at night

Hot sidewalks pulse

Through my veins

Somewhere close by,

Scraps of fresh fruit lay in empty cardboard boxes

Crystallizing the gutter water beneath them

In sweet rhythms

That have accumulated in my mind for weeks

It’s almost July now

These streets feel of paper

The threads of my t-shirt

Melt to a tile roof

Littered in pomegranate seeds

And scraps of fresh bread

Taken from market on the corner

Across from that bar we met at,

Something about the weather this time of year

Makes my body think of yours

Remember when we met last year, sometime in July?

Max Kennedy is a recent-ish graduate of SFSU’s Creative Writing program, where he studied poetics and playwriting. He has been published in a few print and online magazines, such as Xpress Magazine, As Of Late, Ramblr Magazine and Yes Poetry's ebook The Queer Body. He works in Los Angeles as a content creator and creative copywriter for top beauty brands.

Summer Poetry: Jessica Reidy

BY JESSICA REIDY

Sub Napoli: ode to the skeleton bride of the catacombs

In the search for orange

blossoms I dug my trowel into raw soil,

stirred, and felt an aching in the fort.

The earth at Napoli is the blood

of Vesuvius; the dust of mummified bodies

rubbed with oil of myrrh, smoked

by incense; and ripe tomatoes.

Worship these skulls, nameless as children,

their faces shed for their remainders. Pray

to anonymous rib cages so they do for you

what you do for them. A film

of cinder dust coats the long-gone tongues.

I am you, they chanted

in piles of volcanic mud, in blazing

catacombs. In the orange light

petals tumble and crown the bride taken

after her conjugal rites, her cheekbones

sharp and white, her sockets stuffed

with gentian from well-wishers, from pilgrims.

Young women asked her for blessings, find me

a husband—bring me the luck you lost. Does death

give you the broken pieces to give away?

I am you, she replies.

Blossoms turn up their stamen faces

all ash and oil down these understreets.

Jessica Reidy is a Brooklyn-based writer and professor. She is the winner of the Penelope Nivens award for Creative nonfiction, and her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net. Her poetry, fiction, and nonfiction have appeared in Narrative Magazine as Short Story of the Week, The Los Angeles Review, Prairie Schooner, and other journals. She’s a Kripalu-certified yoga instructor, offering yoga and creative writing workshops. She also works her Romani (“Gypsy”) family trades, fortune telling, energy healing, and dancing. Additionally, she is an artist and art model working with a number of artists and studios in the city. She is currently writing her first book.

Summer Poetry: Emily X.R. Pan

BY EMILY X.R. PAN

Missed Dance

I wander over cobblestones

dreaming idly of lips

brought to life in mirrors

Is it a slash of lipstick

or pomegranate seeds

dripping those underworld promises?

Deep inhale night

leads me across a bridge

they say the Seine has a stink

Exhale exhale all

I got was the smell of stars falling

out of love

But rewind

first we met dancing

our eyes made the greeting

I smiled at the long dark hair

the pair of red lips

over his shoulder

He thought my glittering teeth

were for him

they always do

I love this song he said

twirled me like a doll

until I was dizzy and she was gone

In the morning light

my teeth were not the dagger

I kept on me just in case

Under the sun we kicked

our naked feet

across guitar-string grass

He pressed his mouth to my ear

to drink of me

and all I thought of were her silver shoes

Emily X.R. Pan is the New York Times bestselling author of THE ASTONISHING COLOR OF AFTER, which won the APALA Honor Award and the Walter Honor Award, received six starred reviews, was an L.A. Times Book Prize finalist, and was longlisted for the Carnegie Medal, among other accolades. She lives in Brooklyn, New York. Visit Emily online at exrpan.com, and find her on Twitter and Instagram: @exrpan.

.