An interview with S. Elizabeth

by Lisa Marie Basile

This interview is part of our new Creator Series, a series of Q&Aa designed to help you get to know people who are writing, making, and doing beautiful things.

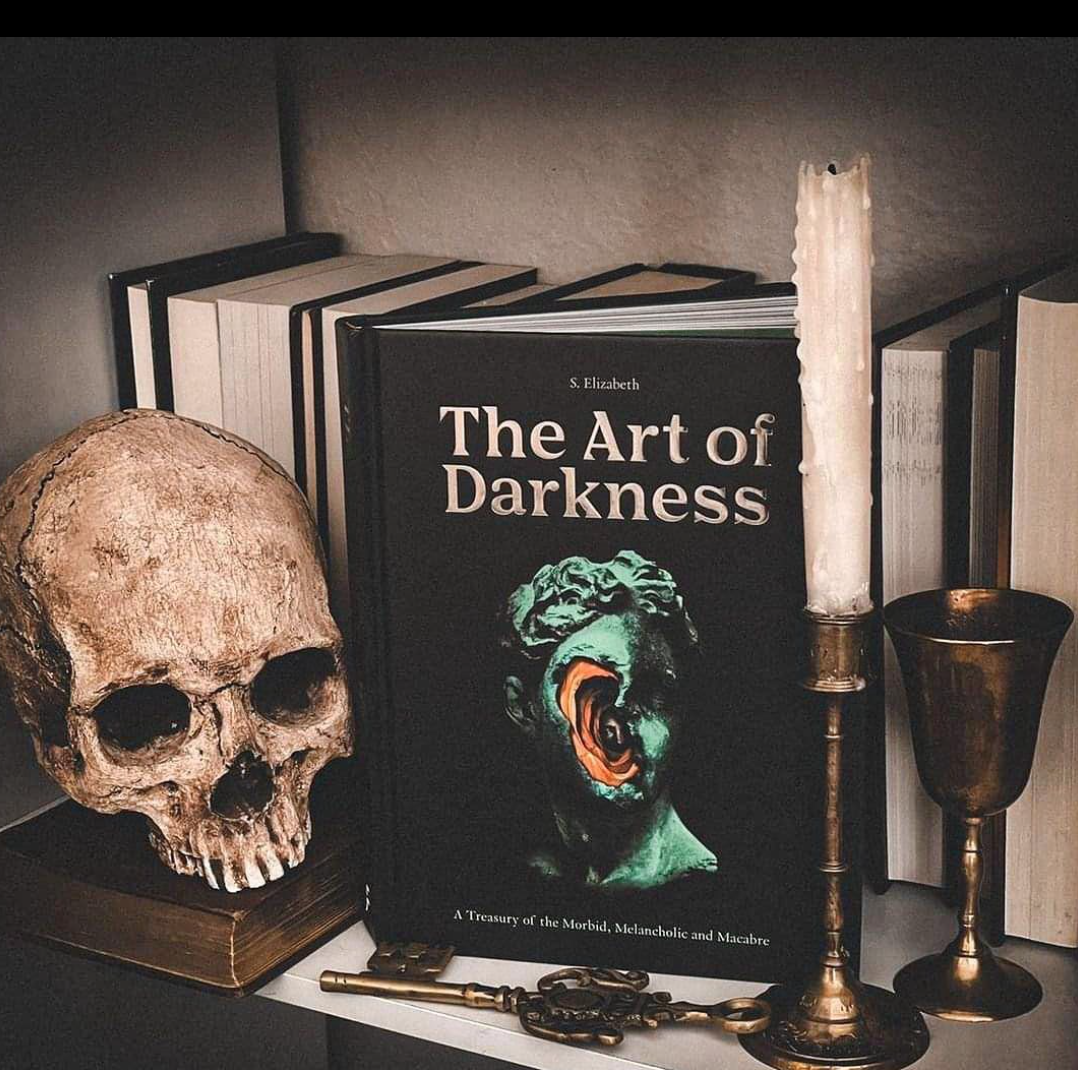

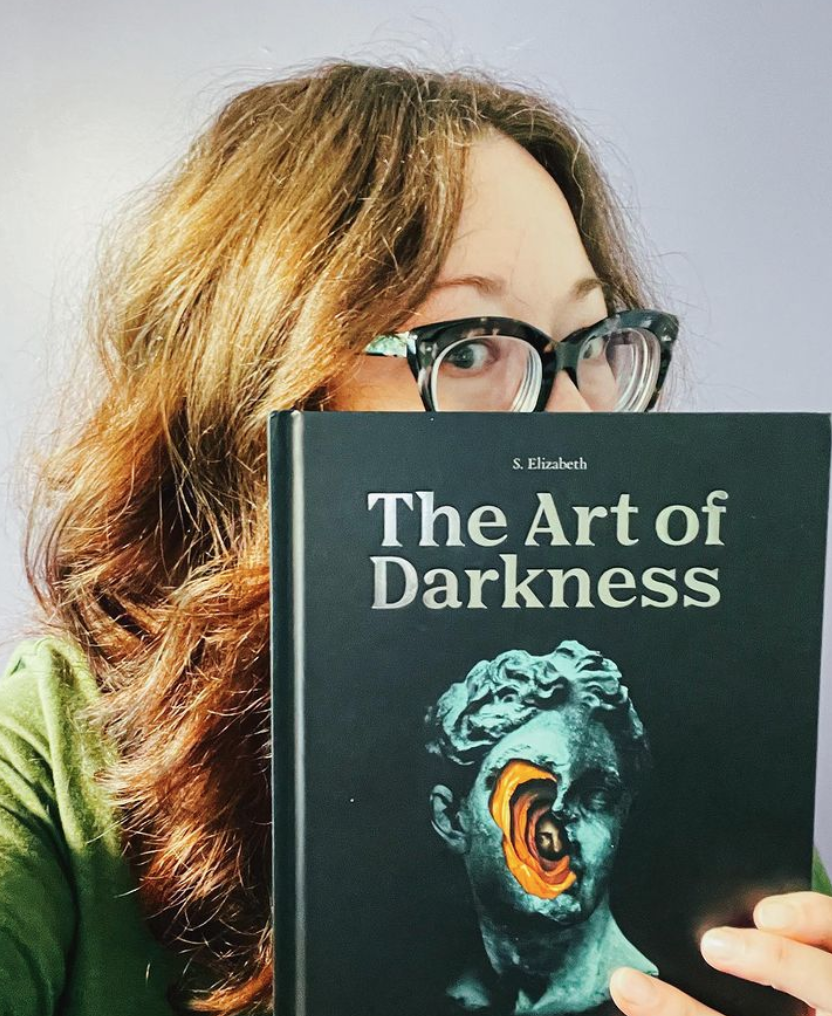

I first discovered S. Elizabeth’s brilliance years ago, when stumbling onto their radiantly macabre, meticulously curated blog, Unquiet Things — a space that I consider a sort of post-graduate education in darkness. The author of two books, The Art of Darkness: A Treasury of the Morbid, Melancholic and Macabre and The Art of the Occult: A Visual Sourcebook for the Modern Mystic, I wanted to ask S. Elizabeth about their influences and inspirations. I hope you’ll enjoy this delightfully detailed, magical, and delicious conversation. I have to say, this is one of my favorite interviews ever done.

Sit by the window, grab a cup of berry-flavored tea or an elderberry spritz and dive in.

Lisa Marie Basile: I’d love to hear more about your book, The Art of Darkness: A Treasury of the Morbid, Melancholic and Macabre. I adored your first book, The Art of the Occult: A Visual Sourcebook for the Modern Mystic (and it’s a cool bonus that we’re press siblings!). What inspired this one? As a self-professed darkling, I want to hear every luscious detail — and I think our Luna Luna readers do, too. I can’t think of a better person to have created this compendium for us.

So the short answer is that The Art of Darkness: A Treasury of the Morbid, Melancholic and Macabre is a beautiful book densely packed with visual arts of the haunting, harrowing, and horrifying variety, and which asks the question "what comfort can be found in facing these demons?" It is inspired by a lifetime's worth of obsession with the dark and what can be found seething in the shadows when we stop being too frightened to peek. Or when we embrace these fears and anxieties, and we peer into the void, anyway!

When I was a child, I loved things all fairy and "flowerdy" (my 5 year old term for heaps of blossoms and blooms). think I was a cottage core early adopter, hee hee! I was terrified of ugly, scary, angry, wild things: Lou Ferrigno as the Incredible Hulk; the feral alien otherworldly vibe of my cousin's freaky KISS posters, and honestly, as silly as it sounds, George Hamilton as some vampire guy in a film called Love at First Bite scared the shit out of me! And I think that was meant to be a comedy! And Scooby Doo? Man, that gave me nightmares.

But somewhere along the way, that panic and fright regarding the bloodsuckers and monsters from outer space began to give way to fascination, and whereas I would once hide my face behind a pillow when something scary was happening, I now began to feel the itchy urge to peek. As I grew older, the fascination with fearsome things slowly turned into an obsession, and, much like a nerdy vampire creep myself, I began to gobble up and devour every bit of frightening or creepy media that came my way.

From literature and film, to music and art, from that time forward, I was hungry for all things unearthly and strange, ghastly and ghostly, gruesome and grotesque. I also grew up in a household with a mother who was an astrologer, who had tarot cards tucked into every nook and cranny, and mysterious artworks hung on every wall. All of her relationships, whether friends or romantic entanglements, were with bohemian weirdos and heavily tinged with magic and mysticism.

My former stepfather for a long time ran a small rare occult book business; I worked with him for a spell many years ago, and it was an incredible experience. Just me and these beautiful old books full of magic and witchcraft and demonology all day long! For a bookworm introvert with a penchant for the esoteric and obscure, that was as close to paradise that I will ever get! These interests and inclinations festered and blossomed and grew alongside me, inside me, over the years and are now what inform and inspire my writing, most of which can be found at my blog Unquiet Things, where I ramble about art, music, fashion, perfume, anxiety, and grief–particularly as these subjects intersect with horror, the supernatural, and death.

There's A LOT of art there. Art is another longtime fascination of mine. These two obsessions—art and darkness—became so deeply entwined for me over time that to celebrate them in a book seemed like the most obvious thing in the world.

“I’ve always felt like such an invisible nothing...and I know that I give away of myself more than I will ever get back in return...it’s the sharing of these little pieces of myself in all of these different places that somehow, paradoxically, builds me back up.”

Lisa Marie Basile: With such a brilliant mind, your trail of inspiration must run deep. Can you tell us what sets you ablaze?

It's funny—this is a question I love to ask artists and creatives when I am the one doing the interviewing, but it turns out that it's not easy to put into words! Or rather, while I can definitely list some inspirations, I'm hesitant to say as to whether or not they are even apparent in my own writing. Dracula by Bram Stoker and Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca were two books that I read when I was 11 years old or so, and I was thrilled to read the intense gloominess and atmosphere of excessive dread and mystery that each of these stories conjured for me.

By that age, I had also read and re-read Louise Fitzhugh's Harriet the Spy a dozen times and while I knew even then that Harriet was a pretty flawed character, I loved her and wanted to BE her with her notebook and nosiness and creeping into people's houses just to see what sort of boring things that they get up to. In college, I discovered Sei Shōnagon. This Heian-era mean girl and OG blogger sorta felt like an adult, more polished Harriet who moved up in the world. I have long loved the writings of this Japanese author, poet, and a court lady : her elegant lists, her acerbic observations, her beautifully intimate and wonderfully catty diaries–all of her anecdotes and opinions and inner dialogue, from the excruciating minutiae of everyday life, to the exquisite poetry she composed connecting and expanding these trifling, fragmented instances to the broader aspects of lived human experience; these strangely random and tangential stories have informed and inspired my own writings for many, many years now.

Also, I’d probably be remiss in leaving out that frustrating old H.P. Lovecraft. His stories are dense with florid description and also packed with racism and xenophobia but he is a part of my past self and I can’t pretend I never read his writings or that his concepts of madness-inducing cosmic horrors haven’t inspired some of my favorite contemporary authors–writers who have taken these ideas and improved upon them immeasurably.

Also, I won’t lie. When I am writing a review for a particularly odious perfume, I may employ the use of a internet Lovecraftian adjective generator for my purposes. Cinematically, I love the works of Jean Rollin and Dario Argento–the former, visual poetry of sensual horror, uncanny beauty and perverse, morbid delights, (read: swoony lesbian vampires) and the latter a creator of gorgeously lurid giallo films. All of these movies are equally absurd and nonsensical, but dang are they pretty. If it’s got exquisite humans wearing breathtaking fashion and swanning about castles or stately manors or even glittering discos or murky alleyways–I am all-in.

Conversely, I do love the gentle, heartwarming charm of a beautifully animated Studio Ghibli film. I love both King Diamond and Weird Al. Lana del Rey and Anna von Hausswolff. Golden age illustrations of elegantly levitating fairies in a lush vibrant summer garden and the gothic charcoal rendering of melancholy moth singed by a candle’s flame. My own writing is probably some strange patchwork of all of these things, the sentimental, the spooky, the silly.

Sometimes I can even channel a less-talented, dopier Mary Oliver:

7am garden poem

Burying elderberry seeds

in the fog of last night’s rain,

mosquito bit, caterpillar cursed,

a spider looked at me sideways—

I know my business, bugs!

Tend to your own!

Lisa Marie Basile: How does the muse inhabit you? Give us a peek at your creative process — the good and the challenging.

For a very long time my process involved being too terrified and paralyzed with the thought of failure to begin a project, making myself miserable for a number of days/weeks/months dreading doing anything about it while not doing anything about it, and then zipping it all together at the last minute because the only thing worse than failing is not coming through with a thing you had promised to do.

The ONLY thing that lit a fire under me and made me write the thing was that I didn’t want someone upset with me for not having written it. Nowadays I’ve come to the conclusion that I hate the feeling of that dread—it takes up so much space and energy and it sucks all of the life out of everything else you’re doing in the meantime!—more than I fear the failure.

I do whatever it takes to get myself in front of my computer and work on the thing every single day, even if it’s just a few minutes. It always turns out to be longer than that, but the trick is, I was able to get myself there because I promised myself “you only have to do the bare minimum today.”

Somehow, that makes it not so scary for me, and as cheesy as it sounds, those snippets add up over time and by the time your deadline rears its head you’re like “oh, I only need to make a few tweaks, everything I need is all already here!”

Another trick (yes, I have to trick myself a lot) is something I read in an interview with one of the big deal writers for The Simpsons. He said something along the lines of just sit down and get it all out on paper or the computer monitor or whatever, no matter how bad it is, just write it and come back to it again later. The next day, it’s already there. Like a crappy little elf wrote it for you overnight. It’s turned the process of doing something that feels impossible (beginning a thing from nothing) into something that feels more bearable (re-writing/editing a thing that’s already there.)

Something else I’ve learned is that if I am stuck, just walk away. Banging my head against the wall and agonizing about it never helps? But you know what does? For me, anyway? Going on a walk. There is something deeply meditative about placing one foot in front of the other and carrying yourself forward. You don’t have to think about anything else about making it to the next mailbox or the next block or around the neighborhood or whatever.

The funny thing is…that’s when all of the thoughts sneak in! I’ve read a few articles on how walking engages some sort of cognitive function in your brain that just isn’t activated from sitting at our desks. Our sensory systems work at their best when they’re moving about the world. So for me, taking a walk helps. I end up planing my day, I compose poems and emails and silly tweets for Twitter. I daydream and let my imagination run away with me.

Sometimes, in the mindlessness of steps walked becoming miles traveled, the inner paths my ruminations take will lead me to interesting places with new ideas or present solutions to problems I was subconsciously working out. I come up with my best interview questions, my favorite article titles, and my most intriguing lines of inquiry during these strolls. For other people that might mean stepping away from their project to work on a puzzle or do some gardening or make a quiche or whatever. Do anything for an hour or so that is NOT the writing that is stressing you out.

Lisa Marie Basile: Do you have any creative rituals? Do tell.

I always have to have my hair tied back. I have some weird sensory issues and if I get overstimulated from a stray hair tickling my nose, I get to the point where I want to sweep everything off my desk in a fit of melodrama and lay on the floor and sob.

Perfume is a must! If I’m trying to get serious about a piece I am writing, I will wear something with a bit of gravitas, like Serge Lutens Gris Clair, a sort of somber, sedate lavender. Or, for example, right now I am writing a book about fantasy art and I am wearing Celestial Gala from Scent Trunk, all milky gossamer wings stardust’s effervescent chill. I keep close at hand a notebook full of scribblings…words or turns of phrase from the books I’ve been reading, passages that are beautiful or strange or that I want to look into further. This is a precious little book of inspiration that sometimes sparks an idea for a whole new thing or that can maybe just serve to fill in a blank or two.

Lisa Marie Basile: Whenever I read your words, your descriptions (especially in your fragrance series, Midnight Stinks), or even these responses, I think, ‘damn, you are SO Taurean!’ Please indulge me — how does Taurus move through your life?

Taurus sun/Capricorn rising/Libra moon, here. When I was a child, my chief obsessions were flowers, glittering jewelry, pretty dresses, and watching my grandmother cook. Before the age that others begin to make an impression on me; before I learned to read and discovered other interests through the characters inhabiting the worlds of those pages; before I realize my mother is an astrologer who has apparently charted my every move well in advance—before all of those things, I was a kid who liked to be by myself, who was quiet and reserved and slow to warm to others.

I loved to help my grandmother roll pie crusts, and form doughy dumplings to drop into broth from the tip of a spoon; I liked to crawl into my mother's garden and play with the snapdragons and marigolds (although I really hated getting dirty!) and I loved—LOVED—playing "dress up" and planning fancy tea parties.

As an adult, all of those things remain true. Of course, my selective absorption of all of my mother's Linda Goodman books (I really only ever read about my own zodiac sign, ha!) probably solidified much it at an impressionable age. I continue to move through the world in the most Taurean of ways, I think. I love my solitude and I am still quite reticent and aloof when it comes to being in groups of people.

I'm not unfriendly, it's just...I can't handle more than one person at a time! So I'm afraid I retreat into myself on those occasions. And the memes are painfully true—I do have stupidly expensive taste. No matter what it is, I mean I could be walking into Petsmart for cat food or at the hardware store (even though I hate the hardware store!) and somehow zero in on the most expensive cat treats or toilet seat or whatever. It's not a helpful superpower!

I love both luxury and comfort; I have got a cabinet full of probably thousands of dollars worth of perfume, and yet I sleep in a ratty old tee shirt that's got holes in the armpits because it's so beautifully, perfectly worn-in, and cozy. I love to cook and I love to eat, and you can see that in my soft, round body. But you can also see that in the way I enjoy feeding people something delicious, that makes them feel good. I still love flowers and I still hate getting dirty, so while you may see me in my garden, gingerly digging in the dirt to plant something small, or harvest a tomato or two, generally my thumb is not particularly green and you'll never see me camping. I am not "outdoorsy!"

I'm in my head a lot—I am a pro-daydreamer, but it's not especially high-brow or cerebral up in there. I don't have scholarly, academic, or philosophical leanings. Although certainly lots of pre-writing work and fleeting bits of poetry and wordplay swirl around in there. Still, I have to coax all of that out onto a computer screen or a notepad and get it all tangibly in front of me to make sense of it.

I don't know if that's particularly Taurean, but I imagine my Capricorn rising gives me a weird ambitious/competitive streak that is probably a good and necessary contrast in order to motivate me to do anything with any nonsense that does make it out of my brain.

TLDR; because in typical, plodding, make-a-long-story-longer Taurean fashion, I am taking a long time to get to the point: I love food and beauty and luxury and comfort; I'm reserved and in my head a lot and I didn't mention it above but yes I can absolutely hold a grudge forever but if I love you, I am probably going to love you forever, too.

Oh. And I am absolutely OBSESSED with Scorpios. While I don’t mean to generalize, I can say that in my experience, there are two types of Scorpios: the one that is Very A Lot, they don’t hold back, you always know what they are thinking and they practically flay themselves open for you. They want you to have all of them, even and especially the ugly and scary bits. They wear their shadow side on their sleeve and their shadows aren’t very subtle, either.

The other kind of Scorpio is not exactly the secretive, silent-type, but their shadows are shrewd and sharp and you might not get to see them right away; you always recognize they are there and you are inexplicably drawn to them like a moth to flame.

I am the furthest thing from a Scorpio, but I am also a secret Scorpio.

“Before the age that others begin to make an impression on me; before I learned to read and discovered other interests through the characters inhabiting the worlds of those pages; before I realize my mother is an astrologer who has apparently charted my every move well in advance—before all of those things, I was a kid who liked to be by myself, who was quiet and reserved and slow to warm to others. ”

Lisa Marie Basile: I am always curious as to how someone’s background, culture, identity, or belief system shapes their work. Can you share a bit about this?

I think my work is hugely informed by my identity in terms of invisibility. It’s a strange/scary thing to talk about because I don’t want anyone to ever think I am somehow mocking their experience as being a nonbinary person, for example, but I was having a conversation with a friend a few months ago after they had come out as nonbinary. I admitted to them that I have never felt like a woman/girl, like a she/her — but that he/him and they/them feel wrong too. I had previously said this to my sister, who responded with “so…do we call you IT?” She was only half serious, but I almost started weeping.

This is going to sound weird and probably very wrong because who wants to be referred to as “it”? Me. I do. That felt perfect to me after a lifetime of living as me, as one who doesn’t feel like a “someone.” I don’t even feel like a person, much less a man or a woman.

I don’t feel like this thing or that thing, because most of the time I don’t even feel here, as a thing that exists. I think my writing and what I put of myself out into the world is very reflective of these feelings of impalpability and unreality, even though I’ve never any of this out loud, in these words.

Lisa Marie Basile: Who do you look up to? I’m so curious about contemporary writers and artists who inspire you.

Three writers and friends who continuously inspire me are Sonya Vatomsky (@coolniceghost ) whose poetry is swoony and sharp and sly and whose essays and other writings are so, so fucking smart; Maika (@liquidnight ) whose words are always so compassionate and thoughtful and perceptive–even when writing about their own experiences, you, the reader feel so breathtakingly, heartbreaking seen; and Nuri McBride (@deathandscent ) a perfumer, writer, and curator whose work centers on olfactive cultural education, and anything she creates is going to be an astonishingly researched, illuminating, insightful journey. Sonya, Maika, and Nuri have all bolstered, supported, and encouraged me in the most gentle and relentless of ways, and they are each deeply special, wondrous humans.

Lisa Marie Basile: I am curious about your thoughts on publishing, promoting, and merging the professional with your, well essence — of creativity and beauty and exploration. I have truly struggled with it all.

In fact, I feel changed — perhaps not always positively — by the experience of publishing. It has taken time to rebuild my Artist self, to step back from going and doing and making and simply rest or take stock. I think once you (or I) share with the world, something dies a little (#scorpio) and you have to work to resurrect it. What are your thoughts on it all?

I thought I would feel more changed by the process of publishing, to be honest. I thought having a book I had written out in the world, on people's shelves, in their hands, would somehow...I don't know...make me feel less sad about having a complicated relationship with my dead mom? Less traumatized by a past relationship full of abuse and gaslighting and manipulation where my identity and self-esteem were ground into the dirt, into nothing? Less shitty about having a less-than-ideal-looking human body that I've been shamed for ever since I can remember? Less scared of everything, all of it, all the time?

Turns out: nope. Having published a book, having published—two books—by this time next month, just means I am all of those things still, but also with some publications out in the world. I still work the same day job I've had for the past 17 years; I don't love it, but in typical Taurean fashion I like my stability and I don't feel comfortable with the idea of just quitting my job and trying to write full-time.

I don't want to "hustle," I don't want to have to agree to write about things I am not interested in so that I can afford to pay my bills. I am just not into any of that. While I am doing as much promoting of my books as I can, I'm not doing anything that feels disingenuous, that doesn't feel like me: you'll never see me doing book tours or speaking on panels or even live-AMAs or anything like that. I promoted them by interviewing the artists in them. I worked them into perfume reviews or little fashion ensemble collages that I then share on social media, or sharing playlists of music inspired by them. These are all things I enjoy doing, and would do anyway, and it was actually a treat to include my book and writings in them. And along with that, I guess I haven't felt anything inside me die because—except for the writing of the book—I don't think I gave *every* piece of myself to the process.

And that's not me patting myself on the back. It's me being boring and practical. I have a job to fall back on. If this book or that book flops, it's not going to kill me. Maybe my ego. But not financially. I'm not rich, I don't have a lot of money. And the money I have made from these books is negligible (that's another thing people need to know about writing books, I think.

There's just...not a lot of money in it.) I know that's not a very exciting or beautiful answer but I do think it is a genuine, practical, Taurus answer. I did exactly what was required of me for these books, in exactly the way I wanted to do it, and no more. Although...I did at one point say that I was NEVER going to be on a podcast (too scary!) but then over the course of the next six months I was interviewed on four podcasts, so ...so much for that, I guess.

I don't know if I adequately answered that question. I've been burnt out, sure. Since 2019 I have written three books (well, I am working on my third) I continue to blog and write for other platforms when it interests me, I post regularly on social media, I started a Patreon that I try to write for once a week, I started and grew a TikTok account where I share perfume reviews almost every day, I put together a press kit, I am in the midst of developing a newsletter and while all of these things sound like professional tools, to me, it's just a lot of fun.

I love doing stuff like this, it's all a beautiful exploration to me. It's A LOT and I need a break every once in a while but I'd probably be doing all of that even if I never published a book! As crappy as social media makes me feel sometimes, the comparison aspect of it, that is, I LOVE it. I really do.

As shy and squirrely as I am, this is how I share and connect with people. I love all of the like-minded souls and kindred spirits that I have encountered through all of these platforms. I've always felt like such an invisible nothing...and I know that I give away of myself more than I will ever get back in return...it's the sharing of these little pieces of myself in all of these different places that somehow, paradoxically, builds me back up.

S.Elizabeth is a writer, curator, and frill-seeker. Her essays and interviews focusing on esoteric art have appeared in Haute Macabre, Coilhouse, Dirge Magazine, Death & The Maiden, and her occulture blog Unquiet Things, which intersects music, fashion, horror, perfume, and grief. She is the cocreator of The Occult Activity Book Vol. 1 and 2 and the author of The Art of the Occult (2020), The Art of Darkness (2022), and The Art of Fantasy (2023)

Lisa Marie Basile is the founding editor of Luna Luna Magazine. She’s also the author of a few books of poetry and nonfiction, including Light Magic for Dark Times, The Magical Writing Grimoire, Nympholepsy, Andalucia, and more. She’s a health journalist and chronic illness advocate by day. By night, she’s working on an autofictional novella for Clash Books.

Her work has been nominated for several Pushcart Prizes and has appeared in Best Small Fictions, Best American Poetry, and Best American Experimental Writing. Her work can be found in The New York Times, Atlas Review, Spork, Entropy, Narratively, and more. She has an MFA from The New School.