Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York, although originally from the rings of Saturn. Joanna is the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, Xenos, Sexting Ghosts, No(body), and A Love Story (Vegetarian Alcoholic Press, 2021). They are the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing By Survivors of Sexual Assault and the illustrator of Dead Tongue, a poetry collection by Bunkong Tuon as well as Raven King, a poetry collection by Fox Henry Frazier (Yes Poetry, 2021). Joanna received a MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Currently, Joanna is the founder of Yes, Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine.

Read MoreReconstructing History: Lauren Russell’s 'Descent'

Veronica Silva is a Provost Fellow at the University of Central Florida, where she is currently pursuing her MFA in poetry. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in PANK Magazine, The Acentos Review, The Blood Pudding, and Pleiades.

Speaking con su Sombra: The Magic of La Poesia

Adrian Ernesto Cepeda is the author of Speaking con su Sombra published in 2021 by Alegría Publishing, La Belle Ajar, a collection of cento poems inspired by Sylvia Plath's 1963 novel, published in 2020 by CLASH Books, Between the Spine a collection of erotic love poems published with Picture Show Press, the full-length poetry collection Flashes & Verses...Becoming Attractions from Unsolicited Press and the poetry chapbook So Many Flowers, So Little Time from Red Mare Press. And, CLASH Books is publishing the much-anticipated poetry collection, We Are the Ones Possessed, in 2022.

Read MoreMy Nonlinear Pregnancy Journey

Kailey Tedesco is the author of These Ghosts of Mine, Siamese (Dancing Girl Press) and the forthcoming full-length collection, She Used to be on a Milk Carton (April Gloaming Publications). She is the co-founding editor-in-chief of Rag Queen Periodical and a member of the Poetry Brothel. She received her MFA in creative writing from Arcadia University, and she now teaches literature at several local colleges. Her poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. You can find her work in Prelude, Bellevue Literary Review, Sugar House Review, Poetry Quarterly, Hello Giggles, UltraCulture, and more. For more information, please visit kaileytedesco.com.

Read MoreJoanna C. Valente

Illustrations by Joanna C. Valente for Fox Henry Frazier's 'Raven King'

Below are three illustrations (with one above as well) created by our editor Joanna C. Valente for Fox Henry Frazier’s forthcoming book, Raven King (out from Yes Poetry in November 2021). You can preorder the book bundle here (which includes music, the book, and more).

Joanna C. Valente

Joanna C. Valente

Joanna C. Valente

Avian Protectors: Honoring and Celebrating Their Messages

By Christina Rosso

My father, born in the fall of 1951, has always loved the haunting, mind-bending stories found in Alfred Hitchcock’s films and Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone. I remember spending New Years Eve and Day snuggled on the couch watching a marathon of the television sensation. Of spending sick days with Grace Kelly, Cary Grant, and Jimmy Stewart on the French Riveria or in a crowded New York apartment complex. I can’t recall the first time I saw Hitchcock’s 1963 The Birds, a loose adaptation of the 1952 Daphne Du Maurier short story with the same name, however, I remember carrying a sense of avian dread. A feeling in my bones that birds could declare war on the human faction whenever they grew tired of our antics.

Birds fly through mythology and folklore. Some are omens of death, while others have regenerative abilities. Some are half-human, half-bird, often femme-bodied, who lure men to their untimely deaths. In Egyptian mythology, Ra, a falcon-headed deity, is the Sun God. As of May 2021, there are an estimated 50 billion to 430 billion birds on Planet Earth. These avian creatures are an integral part of our ecosystem, yet how often do we pause to acknowledge their chirping or cawing presence? For me, it took a part-time job at a very famous abandoned prison.

For nine months, I worked as a historic tour guide at Eastern State Penitentiary in North Philadelphia. Some posit it to be one of the most haunted places in America, with stories of nefarious and heckling ghouls throughout the eleven-acre grounds. In my experience, the abandoned prison is haunted by a terrible history of racism and mass incarceration. Much lore surrounds Eastern State, as does superstition. One superstition of sorts is this: one employee will find all of the dead and dying birds on site (of which there are a considerable amount). When that person leaves, a new person will begin to discover the birds. In the Spring and Summer of 2016, I was the bird finder at the penitentiary.

Often baby birds would fall from their nests onto the dusty slabs of pavement. The first time I found one, I had to give a ten-minute tour of the punishment cells, an earlier form of solitary confinement that continues to plague our prison system today. When I resurfaced from the underground space, the bird had been trampled by inobservant tourists. I promised that bird I wouldn’t let that happen again. After that, each time I found a dying bird on-site, I made sure these animals died with dignity. Sometimes that meant sitting with them, shielding them from being stepped on by visitors, or taking leaves and moving them off the path to a more peaceful place.

I learned quickly that it was worse when they were still alive, their tiny lungs laboring for breath. Long red gashes quivering across their pink, featherless bodies until the wheezing stopped, silence and death ringing in my ears. That year, it seemed that dead and dying birds surrounded me. Everywhere I looked, they were splattered on the sidewalk of my South Philadelphia neighborhood or in the grass at the nearby park. I always stopped to tell them how sorry I was, and if I was able, I collected their bodies, putting them to rest.

Around this time I started drafting a short story collection about magic, identity, and power. Set in New Orleans, I took inspiration from my favorite city and my favorite stories, real and imagined, about witches and goddesses and monsters in the shadows. I shaped a character in part after the Greek Goddess Demeter and in part after myself. A woman whose purpose was to travel to the plane in-between life and death and help the recently departed find peace. I had this character find dead and dying creatures as a child—cats, alligators, and birds. I told myself even if it weren’t possible for me to become this character, perhaps I could still help the animals that sought me out find peace.

I often tell my husband that to some I must appear unhinged the way I walk around Philadelphia and now its suburbs talking to birds as though I’m Snow White. I wish them good morning. I ask how they slept. I thank them for their saccharine chirping and the pleasant joy of watching them fly from one tree to the next. I always feel a swell of gratitude when these birds come to me alive, with the possibility of flying anywhere and seeing anything. And when I find them at the end of their journey, I hope they had a wonderful life.

Since that summer at Eastern State Penitentiary, I have considered birds to be one of my familiars. In European and American folklore, familiars were believed to be supernatural entities that assisted witches with their magical practices. I choose to use this term instead of spirit animal or power animal, as I do not want to further appropriate or cause harm to Indigenous cultures and their language. For me, a familiar is any animal I feel a deep connection with. One in which I feel a mutual understanding and respect. I believe these animals have found me and chosen me. This is especially true with birds.

When we came back to tour our home a second time, my husband and I were allowed to roam the property by ourselves. Alex went through the house, registering every detail of it while I explored outside. In the front yard, a robin landed before me. At that moment, I knew this was our house. I have always been someone who gets “feelings” about a place and takes messages from the universe seriously. This was my message. A robin means new beginnings, hope, and good things to come. We submitted an offer on the house the following day.

Since moving into this home, I have worked on becoming acquainted with all of my bird friends, or avian protectors, as I like to call them. The robin returns daily, as does a crow, several catbirds and mourning doves. On the morning I cleansed our home of negative energy, I found a catbird feather on the side porch. Catbirds, as particularly vocal birds, offer lessons in communication, by asking us to both practice listening and singing our own songs. Their energy is rejuvenating, optimistic, and inspiring. Perhaps this catbird is reminding me that my voice matters and that this new home is the perfect space to manifest the projects I’ve long been putting off. I brought this feather inside and have now collected several more offerings from my various avian protectors. I plan to meditate on these creatures’ symbolism and messages.

Now that I’m settling into life at the new house, I want to continue to deepen my relationship with the birds that frequent the trees and plant life in my yard. I plan to build a birdfeeder for my familiars to offer them nourishment. I plan to decorate my altar with their feathers and to call their messages and energy before spellwork. Now that I have a yard, I plan to collect and bury any dead birds I find in the neighborhood. I plan to incorporate them into the stories I write. And I plan to talk and listen and sing alongside these incredibly delightful creatures.

In The Birds, Mrs. Bundy, an elderly ornithologist, says to our heroine, Melanie Daniels, “Birds are not aggressive creatures, Miss. They bring beauty into the world. It is mankind, rather... It is mankind, rather, who insists upon making it difficult for life to exist on this planet.” I’ve been thinking about this quote a lot lately, and how I feared birds for so long without ever really knowing them. About how humans bring suffering and destruction to the earth and its creatures. How our culture allows fear to drive us to ignorance. My eyes and ears are open, ready to learn and relearn, to accept any messages offered to me, and for that I am grateful.

Christina Rosso (she/her) is a writer and bookstore owner living outside of Philadelphia with her bearded husband and rescue pup. She is the author of CREOLE CONJURE (Maudlin House, 2021) and SHE IS A BEAST (APEP Publications, 2020). Her writing has been nominated for Best of the Net, Best Small Fictions, and the Pushcart Prize. For more information, visit http://christina-rosso.com or find her on Twitter @Rosso_Christina.

Poetry by Fox Henry Frazier

The Fox-Haired Seer Makes A Pilgrimage to Devil’s Elbow, NY, Where in 1932 A Steam-Shovel Operator Discovered the Skull of an Axe-Murdered Young Woman; and Listens

Not unlike the Vestals in their forced

walks across Rome to prove their bodies

unviolated by men, I conduct my promenade

these nights: my body both water and sieve,

both returned to the earth and ignited

by rage. I pause, lift my skirt to avoid

stepping on it, extend my hand to passing cars. The luckiest

among them will keep driving. Those less fortunate

will deliver me, hot tongue spreading

to all-consuming inferno, the offering of their

human hearts still beating, skulls spiderwebbed

apart by force of impact. Smiling, I’ll thumb

their eyes shut as they rest like unborn

calves against the steering wheel: milky, still.

A precious few will stop for me in rain, open

the door as though to a carriage, their exposed

hearts pure as a distilled spirit, as violent white powder.

I can’t take them. They’ll blink & find my voice

was merely certain tones of wind, curves and visage

a mistake in the brain—hallucinatory

patterns made by wind in a blizzard, or their own

rich somnambulant vision. They’ll scurry

home to their dark houses, light a room, wrap themselves

in blankets, and dream of a paper doll transforming

into smoke, set alight by a brutal boy after he’d made her

scraps with his blade. My last moments illuminate like Leda’s

smothered convulsions against downy breast

and the cleaved immortality that comes

After. And so I take you, beloved, the men used

to say to the young girls they chose to serve Vesta.

Sometimes, I change my clothes, as bored

girls are wont to do: sequins and tulle, late for prom; car

trouble in a taffeta ball gown; or wandering in my own

true Victorian garb, corseted, each breath controlled, abject

in all but my appetites. I stare

into myself—this fury I ignite, what

gift to my daughters who walk

home alone at night: gibbous

reds and yellows eradicating

each other within let tongues

consume the lamb

flickering ravenous silent

save the sporadic, inveterate

ferocious susserate I am

Fox Henry Frazier is a poet and essayist whose first book, The Hydromantic Histories, was selected by Vermont Poet Laureate Chard deNiord as recipient of the 2014 Bright Hill Poetry Award. Her second, Like Ash in the Air After Something Has Burned (2017), was nominated for an Elgin Award. She edited the anthologies Among Margins: Critical and Lyrical Writing on Aesthetics and Political Punch: Contemporary Poems on the Politics of Identity.

Fox was graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Binghamton University, and was honored with fellowships at Columbia University, where she received her MFA. She was Provost’s Fellow at the University of Southern California, where she earned a PhD in Literature and Creative Writing, and served as Poetry Editor of Gold Line Press and a Founding & Managing Editor of Ricochet Editions.

Fox created the small literary press Agape Editions, which she currently manages with the poet Jasmine An. She lives in upstate New York with her daughter, her dogs, her gardens, and her ghosts.

Florian Lidin via Unsplash

Homespun Haints Is Your New Fave Ghost Story Podcast

BY ALEXANDRA COHL & BECKY KILIMNIK

Becky Kilimnik is the co-host and producer of the podcast Homespun Haints, an interview-style and storytelling podcast that celebrates the oral tradition of storytelling as an art form—with ghosts. Throughout its inception, Becky has also pulled from her other expertise as an artist and musician; she composes and plays all of the original music on the podcast and creates original artwork to accompany each episode. Now in their third season and with over 25,000 downloads, Becky and her co-host Diana Doty have cultivated a space where people can feel comfortable sharing and processing the paranormal experiences they have had.

Listen to: Korean Folklore, Death Days, and the Haunted Queens Apartment, or Quarantined With A Ghost

And, as someone who grew up in an Appalachian town and who has deep ties to the art of storytelling, Becky applies both her personal history and her Anthropology degree from Northwestern University to these interviews and in the pre- and post-production stages to really capture just how personal and unique these ghost stories can be. The podcast delights listeners in both expected and unexpected ways: fulfilling the desire for a creepy tale while also inviting laughter, self-reflection—and sometimes tears—with the stories that are told.

You’ve said before on your podcast (specifically the episode with professional storyteller Dr. Hannah Harvey) that “The tradition of storytelling as a celebrated art form is so uniquely Appalachian” and that “It doesn’t seem to have the same weight given to it culturally in other parts of the country.” I’d love to start there: What was the moment (or moments) where you really began to realize this and what were those major differences?

Becky Kilimnik

I spent the first part of my life in northeast Tennessee with only limited exposure to other parts of the world. When I turned seventeen, however, I moved to Chicago to go to college. My first year there, I slowly began to realize there were no storytelling festivals to attend, and no one talked about “storytelling” as a fun pastime. Of course, people there tell stories, just like people all over the world tell stories. And Chicago itself is an amazing hub for two very unique types of storytelling: improv comedy and jazz music. But, the cultural emphasis (which evolved from the combined traditions of Scottish, Irish, and African immigrants and Cherokee residents of the area) on non-scripted orality, practiced in front of a mirror, performed on stage or in front of peers, fluid and changing with every performance, for both the purposes of entertainment and sharing of knowledge, didn’t exist in the same form. And I found the same to be true in other places in America that I’ve lived as well.

Do you remember the first time you heard a ghost story? If so, what was it, and how do you feel like it started to shape who you are today?

I don’t think I could tell you the first ghost story I heard! Honestly, I think my mother was telling me ghost stories before I could even talk. I do remember the first time I heard a professional storyteller tell a ghost story, though. It was at a music workshop I was attending in Jonesborough, TN (I’ve been playing violin since I was four years old so I did a lot of these such workshops), and they hired a storyteller to entertain us during our first night there. I remember her handmade, brightly colored costume that hung off of her arms in twisted strips and how pieces of her costume would whip around her as she gestured.

I also remember the gasps of my little sister as the storyteller moved about the stage, telling us about the woman who ate her own body as she nearly died of hunger one cold winter night. In the story, the woman’s husband finally came back to their log cabin with a deer for dinner, but the woman, now nothing but an animated skeleton, leaped out from behind the cabin’s door and consumed him, too. And that was the end of the story.

At first, I hated the story because I wanted more. I wanted to know if the skeleton woman still wandered the mountains in search of food (of course she did!). I wanted to know what happened next and if the storyteller made the story up herself or pulled it from folklore. But then I realized that none of those things really mattered in a good oral story. The story often ends at the climax; there is no resolution. And the art of the story itself is not in the following of a traditional short story structure—the art is in how the story is told. The drama behind the storyteller’s movements and the inflections in her voice.

At that moment I was instantly in love with storytelling. The ability to entertain and enrapture large groups of people merely with words and gestures seemed like pure magic, and I knew it had to be something I incorporated into my life.

Tell me a little bit about the origin story of Homespun Haints; what prompted the idea for it, why you chose the format for the podcast that you did, and how you see it differing from other paranormal-based podcasts.

Homespun Haints

One of the first things I’ve always asked people when I meet them is “do you have a ghost story?” I’ve always been intrigued by the way people interpret events in their lives that they can’t quite explain. It makes us vulnerable and human, and no matter how people carry themselves, when they start to talk about a ghost encounter they’ve had, they reveal their soul to the world. As far back as I can remember, I’ve had an insatiable hunger for those stories and those moments.

I wanted to find a way to capture those points in time where the person telling their story bears their deepest fears to an audience and connects with their listeners in a profound way. I initially considered starting this project as a written blog, but then I remembered the storytelling traditions from my hometown, and I realized I had to do something that was linear (and oral), experienced moment by moment by the listener as the story unfolded. Podcasting presented itself as the perfect solution. Because of my musical background, I already had experience with recording and editing audio. The rest just took some planning and research.

I feel this podcast is different from other traditional paranormal podcasts because our primary focus is storytelling. Even though all of our stories must be ghost stories to fit with our brand, their magic comes not just from the events within the stories but also from how the story is told and how we react to those stories emotionally. We consider what we’re doing to be more of an art form than anything else.

Oftentimes, your episodes can be a mix of serious, spooky stories, along with dark (and sometimes light!) humor. Why is that approach so important to you and your co-host, Diana Doty? Why not go the “uber spooky” route?

Initially, we did think of going down the “uber spooky” route, but our personalities got in the way. We started throwing humor in because we couldn’t help ourselves! And I think that’s fine. It wasn’t a planned approach or branding initiative; it’s just who we are. Our listeners have told us that a lot of what they like about our show is how genuine we are behind the mics, and we enjoy just being ourselves—weird, spooky women who love to laugh.

By Becky Kilimnik

Plus, a good story is always better if you access more than one emotion while listening to it. A scary story is just a scary story. But a story that makes you laugh, cry, and cover your head with a blanket is going to stay with you for a long time. We want to provide warmth, humor, and fear, and create a well-rounded experience for all of our listeners, no matter what their comfort level with the paranormal is.

You’ve also expressed that in mainstream American culture, the paranormal community (such as who is invited on these types of podcasts) can often times be very whitewashed. Why do you think that is, and what have been the ways that you’ve worked to change that on your own podcast?

If you go on a ghost tour or look up the famous ghosts at a historic site, the stories you’ll hear are disproportionately about rich white people. If you hear about a person of color, especially about an enslaved person, the story may be completely made up or altered to make it more palatable to a white audience. Though plenty of stories have been told in all communities throughout the ages, these sanitized, white-centric stories are the ones that have more often had the advantage of being written down and shared across different types of media.

As storytellers and story-preservers, Diana and I want to do whatever we can to preserve stories from all communities, especially communities that have had their stories lost in the past.

It’s been a little bit of a struggle, I’ll be honest. When we started the podcast, we turned to our friends and family to serve as guests for the show. And many of those people are in very professional jobs and were uncomfortable talking about their ghost stories in a public setting. Many of our guests from the start chose to come on only with our assurances that their anonymity would be protected. When we did start reaching outside of our own circle for guests, we wanted to be sensitive to the fact that, when we have a guest on our show, we know they are doing us a favor. We needed to have a large enough listener audience to provide significant value to our guests in exchange for their time. We promote whatever projects our guests are involved with on our show and in our show notes, so the larger our audience, the larger the value of that exposure is.

Now that we are large enough that we can provide that value, we’ve really set an initiative for this season to seek out more people of color to come onto our show and share stories with us. Part of that work is ensuring that we are creating a space where people of color and their voices will feel safe and respected, so we’re also very upfront with our guests about this initiative; that we want to share diverse viewpoints that much of our audience may not even have considered or know about.

Ghost stories are both entertainment and history, both of which are, unfortunately, very whitewashed in mainstream media and literature. If you’d like to learn a little more about this, I suggest watching the documentary Horror Noire on Shudder, which discusses the evolution of Black actors and characters in the horror fiction genre. Also, there is a great episode of A History of Ghosts called “The Whitewashed Ghost” that discusses the psychology behind the white-centric ghost tour.

LISTEN TO: Filipino Folklore: Manananggal, Engkanto, and Duwende, Oh My! or Sometimes There’s Just Ghosts, on Appalachian Storytelling

I know that you and your co-host really encourage people to share their truths on your podcast—that it isn’t a place to question people’s ghost stories but rather a place to affirm their experience of the world. In the many interviews you’ve conducted and the stories you’ve heard up to this point, what have you learned about the history of supernatural stories and their cultural significance? Has anything surprised you or contradicted what you believed when you first started this podcast?

Our biggest surprise has been how cathartic the storytelling experience can be for our guests! After telling us stories that they’ve kept pent up inside of themselves for years, many of our guests will burst into tears, thank us, tell us that talking to us is akin to therapy. We were not expecting that at all when we started out. We thought we were just going to be sharing some ghost stories; we didn’t realize how many people would benefit from having a place to dig deep into their own pasts, and share stories they didn’t realize they were hiding from. Our commitment to having a non-judgmental, safe space has really paid off in that regard!

Obviously, this isn’t the case for all of our guests. Some of them have told these same stories dozens of times before. But for those that haven’t, it speaks volumes about our culture’s attitude toward true supernatural experiences. Many guests tell us how they’ve experienced ostracization from society, ridicule from family members, even fear of losing their jobs, when they’ve revealed these stories to others. Which is sad when you consider how profound and life-changing some of these experiences have been for some of these people.

Again, this was something that really surprised me, as someone who grew up in an area where sharing ghost stories was just a way of life. I believe everyone should have the opportunity to share their story and should not be punished for seeing the world a little differently than their peers.

So, you do even more than co-host and produce the podcast. You also create original artwork, stop motion YouTube mini-stories, and the original music for each episode. Talk to me about the art first: for the episode artwork, what is the style, and how do you decide which piece out of the whole episode to express visually?

By Becky Kilimnik

I would define my style as “quirky surrealism.” It’s not something I specifically developed; it’s just kind of what comes out of my hands. I began creating a piece of art for each episode because it seemed easier than hunting through stock photography sites for something that fit. I can’t tell you where inspiration for these things comes from—things just pop into my head and I try to replicate it. That’s how the initial pen and ink drawings started. I also began doing a few watercolor paintings as well because they were quick and easy and I could do them in color.

Toward the end of the second season, I started following some pop surrealism artists on Instagram (especially the paintings of Jesús Aguado @jm.aguado), and I became inspired by their work and wanted to try my hand at something similar. My first few works were a combination of oil pastel painting and drawing; pastel has always been my go-to medium for color, and I really enjoyed getting back into it. But, they’re messy and time-consuming, and my husband began grousing about the condition of our dining room as I was working. So, I thought I’d give acrylics a try. I’ve never used them before but I do remember watching my mother paint when I was a young girl, and I took to the medium right away. I’m really enjoying them and will probably stick with them for a while until I become bored and move onto something else.

As for what to express visually for each episode? I try to think of what piece of someone’s story would be the most visually impactful. When I picture the story, what do I see in my mind? And is it something I think I can pull off with a paintbrush? There’s not much more to it than that. The great thing about working with acrylics is that if I don’t like something that I started, I can always paint over it!

What about the YouTube channel? Why stop motion and how does this function as an extension of the podcast?

Our stories are home-grown (hence the “Homespun” in Homespun Haints) but they’re also on the bizarre side. Therefore, I’ve steered away from doing anything too polished visually for the aesthetic of the podcast—I want it to retain a little of that slapped-together feel.

I grew up in the eighties, when stop-motion animation was everywhere, from Claymation shows to special effects. For me, this technique always existed between the realistic and the strange. Plus, I do digital art all the time for my day job and it’s really relaxing to just stop and create with my hands.

Stop motion animation is also quirky, funny, and old-fashioned, just like many of the ghosts we talk about on the show. This style of animation also gives me a chance to create videos from hand-drawn components, just as the art that illustrates the episodes is hand-drawn. Every once in a while, I’ll accidentally get my thumb in a frame as I move pieces around and I just leave it. Those little mistakes just augment that homespun feel.

Now tell me about the music. What is the process behind creating the music for each episode and how does it impact the storytelling aspects of your podcast?

I have several pieces of music that I’ve composed, performed, and produced that I use and re-use throughout the episodes. I generally change it a little from season to season (the first season was piano, the second was digital music, the third is the organ and violin). I came up with the theme song when we first started the show by messing around on the keys; everything since then has been some sort of variation on that theme.

Now for the more detailed answer. I’m a classically trained violinist with strong ties to the bluegrass fiddling of my home area. After I moved to Chicago, I became bored with classical violin and fiddling and started performing with progressive rock and glam rock bands. For eight years, I played in every bar throughout the Hyde Park, Rogers Park and Wicker Park neighborhoods. One stipulation for me being able to play with these groups was I had to learn how to improvise. When you’re hungry, you’ll learn how to do anything. So, I spent nearly a decade refining my improvisation chops.

When I started the podcast, I had barely touched my violin for ten years. Hence, the piano. But quarantine altered everyone’s fate. I accidentally formed a band with some neighbors one drunken night, and before I knew what was happening, I was shredding on the old fiddle again. A few months later, I seem to have acquired a great deal of equipment, pedals, cables, and other strange musical items that just keep appearing in the living room. At one point, a Theremin even showed up.

Now, whenever we need new music for the podcast, I pull on those violin improvisation skills of yore. I’ll pull out my fiddle, go up to a mic, and mess around until something I like comes out. Then I create variations on that, and use editing software to mix, loop, overlap, and combine the tracks until it sounds like something that works with our show.

As for how it impacts the storytelling? I am committed to never using music to enhance or detract from our guests’ stories. Therefore, we only use it at the beginning, end, and interludes in the podcast. Music never flows over our guests’ words. I believe the story itself is enough and adding anything to it would be a disservice to the speaker’s words.

In the production, how do you manage to enhance the oral storytelling (with guests who may not always be natural storytellers) without stripping them of their individual voice?

This is a tough one, but something I’m quite proud of. In a heavy edit, I may move pieces of someone’s story around so that it flows a little better—for instance, if someone accidentally tells the end first, and then says “Oh I forgot to mention….” I may even add extra spaces in between sentences to build suspense if a guest is nervous and speaking quickly. I will often remove excessive filler words (uh, um, like, you know). But I never touch colloquial language. I would never alter an accent. And, we always give the guest the opportunity to listen to their episode before it airs.

Most guests, however, do not require heavy editing. We’ve found that most people, whether they realize it or not, are natural storytellers. Most of our job is just to help them be comfortable, help them figure out a good starting point, and then sit back as the story flows out of them.

What do you feel like folks outside of the paranormal community get wrong about it?

Oh, that’s a tough question. I think there may be the assumption that people who enjoy paranormal stories or who are involved with paranormal events, are a bunch of “scary devil-worshipping creeps.” But in actuality, every single person we have met has been an amazing human being. I think people who love this stuff are used to being on the outside; they have a lot of empathy for anyone else who is used to not fitting in. And they’re just the nicest people ever.

I think there’s also a belief that anyone who believes in ghosts is either completely ungrounded in reality or is trying to take advantage of gullible people (think common beliefs about fortune-tellers and palm-readers). My co-host, Diana, is a former physician with some pretty hefty scientific training under her belt, and our guests are down-to-earth people that just happen to have had some unexplainable experiences. When we’ve interviewed spiritual mediums (and we’ve had quite a few on the show), they are also very truthful about their abilities and their beliefs and have no intention of taking advantage of anyone. In general, we’ve found a great group of people, we’ve formed some strong friendships, and we’re so excited to be a part of such a warm and inviting community.

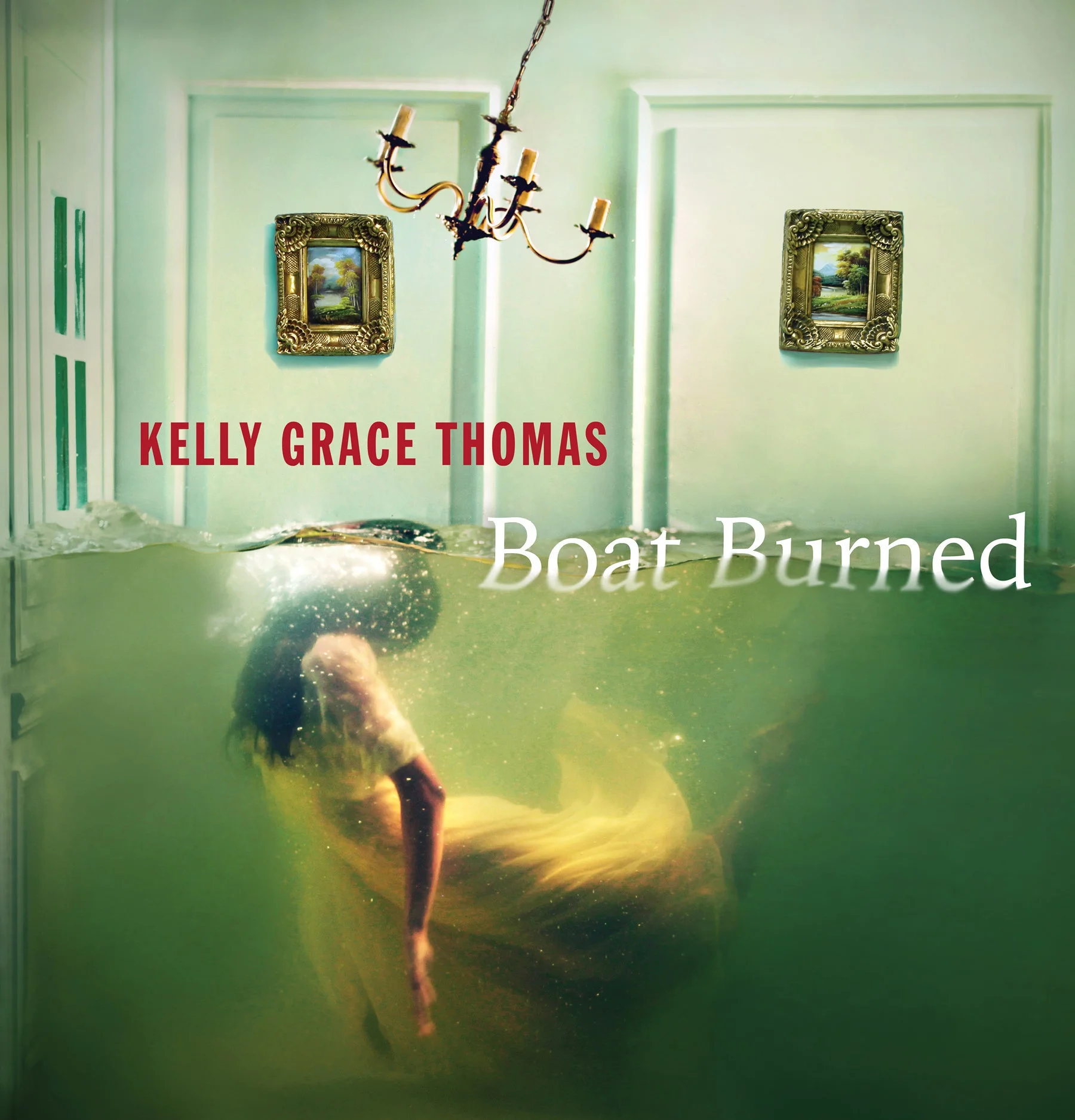

Burning the Boats that Brought Us Here: Madeleine Barnes Interviews Kelly Grace Thomas

BY MADELEINE BARNES & KELLY GRACE THOMAS

Boat Burned by Kelly Grace Thomas

YesYes Books, 2020

110 pages, $16.20

In Boat Burned, Kelly Grace Thomas’ debut poetry collection (YesYes Books, 2020), we join a perceptive, vulnerable, authentic speaker in confronting and untangling the effects of generational and collective trauma on the body. In “Vesseled,” the first poem in the book, she writes: “He boarded me. I burned.” This truth is one she “can’t throw overboard,” and the ocean is her witness as she observes what remains of her.

Thomas’ poetry invites us back to the sea, and its stillness invites us to reflect on tensions that cast shadows over our lives: chaos and order, self-punishment and worth, violence and liberation, trauma and recovery. The speaker desires “to divorce the earth,” and studies leaving “like a chart.” For Thomas, family is a synonym for “horizon.” In the speaker’s family, three women privately struggle with eating disorders but never talk about it—she longs to leave, but struggles to find the exit ramp. It is critical for her to go beyond the horizon, and through interrogations and deconstructions, she attempts to recover. She endures the mangling effects of self-surveillance; secrecy is a lack of oxygen.

Drowning remains a possibility, but the third and final section of the book reveals the beginning of the speaker’s journey toward a reconciliation with her body: “Body, why can’t I remember you / right? I know you’re no life / boat.” Here, the narrative transforms into one of triumph, asking us a critical question—when we are at sea, how do we want to drift? What structures and pressures make this choice ours and not ours?

In writing this book, Thomas endeavored to “recover from womanhood,” and in this interview, she reveals more about what this means to her. She also offers words of encouragement and gives thanks to poets who write about similar themes. She reminds us of all the ways that capitalism profits from our inability to love ourselves; self-love is a life-sustaining skill that no one teaches us. Reading her book, I was reminded of Alice Walker’s assertion that “telling and honoring the truth carries the possibility of transformation and delight.” Thomas uses both metaphor and direct language to deliver her truth. Her candid poetry strikes back against the layers of stigma, silence, and misinformation that compound trauma. “They can’t sink us,” she writes, “if we name ourselves / sea.”

MB: Boat Burned (YesYes Books) openly examines private struggles with trauma and the body. You write with incisive clarity and strength about conditions that thrive in secrecy and are still stigmatized, even in literature. In “Where No One Says Eating Disorder,” you write about a family in which everyone is struggling privately: “When I was young, I pretended / we weren’t sick. Three women. / Three rooms.” We watch the woman in this family struggle in silence and isolation. The poem concludes, “We were so hungry / for anything / to love us back.” Why was it important to you to include your family members’ experiences of trauma and disordered eating in this book, real or imagined?

KGT: Plain and simple: I had to. This story, this struggle, is so much bigger than me. That was important for me to recognize share with readers. So many elements of disordered eating are shrouded in isolation and shame, and that’s what the disorder feeds on, how it survives. Eating disorders are sustained by silence. The less we talk or write about it, the sicker we remain. It took me years to admit that I was punishing myself and trying to control the world around me with food.

Carolina Public Health Magazine states, “A shocking sixty-five percent of American women between the ages of 25 and 45 have disordered eating behaviors, according to the results of a new survey sponsored by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and SELF Magazine.” That means roughly every two out of three women struggle with this. There is so little education and prevention, let alone conversation. I wrote this poem to show readers that this disorder is one that affects many. Growing up, every woman in my household had an eating disorder. We did not admit this to anyone, not even to each other, until almost twenty years later. We spent two decades suffering in isolation. The important question is: Why?

I’d always wanted to write openly about body image issues and eating disorders. This plagued me, but I worried that writing about my body made me a cliché. Women have been programmed to equate their appearance with their intrinsic worth. Industries thrive on women’s insecurity. The less we love ourselves, the more companies profit. This narrative is changing, but progress is slow because these conversations are often had in private. It’s time to start figuring out how we can help—it’s time to heal. It felt irresponsible not to contextualize my own eating disorder within my family—all of us were suffering, yet felt so isolated.

MB: You’ve spoken in the past about metaphor, and this book does a wonderful job of using metaphor to describe a struggle with the body. You write, “I thirst for shelter / I have no faith in. My body: a church / where no one prays.” We watch the speaker “confuse body / for boat.” A mother “unzips the body. / Passes it down. You also show us that there are no metaphors for some aspects of living with an eating disorder. In “No Metaphor For My Mouth,” you write, “I have no more lines memorized. // Nothing dainty // to make you // weep.” Did you make conscious decisions about balancing metaphor with direct description in this book? Recovery-wise, what is the benefit of setting metaphor aside and facing the reality of an illness, however stark?

KGT: What a great question. I don’t think this balancing was conscious, but as I wrote, my writing became more direct. In “Where No One Says Eating Disorder,” it was important to me to depict silence before the first line. In my view, metaphor makes hurt accessible. Metaphor gave me the key to enter the house; it also gave me the hammer. Once inside the house, I could stare at the walls and try understand why I built them before tearing them down.

When I first started to write poetry, I questioned lines that spoke directly. I thought that perhaps they lacked the musicality or depth necessary to capture pain. I have come to realize that there is nothing more vulnerable than letting a simple, direct statement hang in the air, unadorned. It lets readers look pain in the eyes.

MB: In the incisive poem “In An Attempt to Solve For X: Femininity As Word Problem,” you write, “The difference / between shame and guilt is showing / your work.” Shame and guilt continually provoke the speaker, who fights to “turn this shame to sanctuary.” In “At The Bar My Friend Talked of Bodies,” shame is a toxin: “No stomach can digest / shame: a congregation // of rocks. Patient in a / poisoned well.” Does writing play a role in mitigating or coming to terms with shame?

KGT: Yes, writing is an investigative path out of shame. We can’t conquer what we don’t understand. Just like fixing a crack in a foundation, I needed to find the first fracture. When compiling the collection, I noticed that many of my poems speak directly or indirectly about the shame I felt about womanhood, which in turn was linked to my body and perpetual guilt. I have listened closely to the world while taking notes on why shame can sometimes feel like an appropriate response to what the world tells women.

So often I am quick to swallow blame, and the lines you referenced are an attempt to show the reader I know what it is like to live as an apology. It was a chance to call myself out on the page, publicly, directly; it was a promise to write myself stronger. Boat Burned let me identify the guilt and find a path out of the shame. By the time I finished the book, I was no longer ashamed of who I am.

MB: In a recent interview published in [PANK], you spoke about water: “Water will always be stronger than boat. Stronger than gender. It is the hands that hold us, the mother that covers us, the power and grace, that allows us.” What is the relationship between water, control, fertility, and recovery in your work?

My relationship with water is one of the most important relationships in my life. There is a quote by Isak Dinesen: “The cure for anything is saltwater — sweat, tears, or the sea.” This is one of my core beliefs—we came from the sea, and my body and soul are always trying to return.

Growing up, there was a lot of adventure and uncertainty in my life. There was bankruptcy, divorce, eviction, addiction, and of course, eating disorders. The water felt like the only thing that could hold me without making me feel like a burden. I spent a lot of time on boats, sometimes in the middle of nowhere with nothing to do but stare at the sea. Its steady quiet always returned my gaze, pulled me into the peace of a blue horizon, and challenged me to sit with what I was running from. I couldn’t have accessed this stillness without water.

I use water to think about the ebb and flow of life. The ocean holds an understated power. It breaks and breaks, yet still survives. Its breaking is inevitable. We cannot change or influence the ocean; we cannot prevent low tide. The ocean is not concerned with us, and I love that. I reach for water for strength, and to heal whatever is breaking within me. There is so much healing to be done, and water reminds me that healing and recovery are possible.

MB: Eating disorders are still deeply misunderstood and stigmatized. In what ways did you choose to push back against stereotypes or tropes surrounding eating disorders in your writing?

KGT: It is counterproductive to talk about shame and without mapping the origin. Women especially have been programmed to hate their bodies. In The Self Love Experiment by Shannon Kaiser, I read that a whopping 90% of women hate their appearances. This breaks my heart daily. Eating disorders are not only stigmatized but glamourized. In the media, eating disorders are portrayed as a phase. There are so many after-school-special-like tropes I wanted to avoid in my writing: the teenager working out until she passes out, the bathroom scale with its cold steely gaze. These tropes aren’t inaccurate—but so often, movies on this subject are made by people who don’t suffer from eating disorders, and they wind up creating caricatures of sufferers’ pain. Plot points can occlude the real story. Sometimes, a character’s eating disorder is “cured” in an episode or a season.

After 20+ years, I still suffer from ED-related thoughts. Some people who have eating disorders think they are fat, which can lead to feelings to worthlessness, because this country and the media has linked body size to worthiness. We have also been told that shame isn’t sexy, so we punish ourselves further for feeling shame, which buries us further in stigma and silence. At 39, I am still struggling with the relationship I have with my body, which will continue unless I do the work of active unlearning and reprogramming. I am learning not shudder at bad lightning or inquiries about my weight. I want to show people that eating disorders are not rooted in vanity. They are rooted in feelings of unworthiness—so many feel unworthy love and so much more.

Like so many people, I felt unlovable in the body I was in. I wanted to feel like I was worth something, and when I developed an eating disorder, I felt like it was making me worthy of the love I sought. When I would lose a lot of weight, I got lots of positive reinforcement. The problem is that this is an illness. It took me forever to admit that.

MB: Are there any writers who deal with the body in their work in ways that influence you? Conversely, is there anything that frustrates you about other people write or talk about eating disorders?

KGT: There are so many poets who write about the body beautifully. One poem that comes to mind is Jennifer Givhan,’s “I Am Fat, & When You Read this Poem, You Will Be Too.” This poem should be required reading. I also think of the book Helen or My Hunger by Gale Marie Thompson, and To Know Crush by Jennifer Jaxson Berry. Courtney LeBlanc also writes about the body, disordered eating, and body dysmorphia. These poets are outstanding. It frustrates me when people view body image issues as temporary, like a haircut. I’m reminded of Lucille Clifton’s poem, “i am running into a new year.” She writes: “it will be hard to let go / of what i said to myself / about myself / when i was sixteen and /twentysix and thirtysix / even thirtysix.” At 39, I am still trying to heal, still trying to let go and forgive. People don’t understand that this is a long road.

MB: Section IV, the final section, has so much momentum—poems like “How to Storm,” “New/Port,” and “The Only Thing I Own” show us a speaker who finally allows herself to rage. She finds motivation to recover: “There is a part of me / worth keeping.” She implores the body: “Let’s hold each other // honest as wind.” In “Boat/Body,” you write, “I will not kneel / for a man’s affection,” and “They can’t sink us / if we name ourselves / sea.” Can you speak to your experience of writing section four, and the role of anger in both writing and recovery?

KGT: The last section of this book, which I view as a nod toward acceptance or forgiveness, was the hardest section for me to write. While in the middle of writing Boat Burned, I told a young woman friend that I was writing a collection of poems “to try and recover from womanhood,” and “to teach myself how to love myself.”

She asked me if it was working. I was honest and told her it wasn’t. At that point, I wasn’t sure it was possible to recover from womanhood through writing. But I knew that I couldn’t finish this collection in the same place I started. I needed to burn the boats that brought me here, and to walk away and never look back. So I kept on writing and revising until something inside me changed. Silence and subordination were no longer compelling.

In every Speilberg movie, you never see the monster until the end. When we can’t see it, the monster remains terrifying. Writing the last section was about confronting the monster to make it less menacing. The more honest I got in these poems and the more I sent them into the world, the less scary these monsters became. When I am too afraid to address something in my life, I need to put it in a poem. A poem is the first step toward confrontation, the first brick in the road to recovery. This book took about 3 years to write. I am no longer the person I was when I started writing it. I had to chase the why, to unpack every lie I swallowed, to take off the sadness that wore me like a dress, before I could heal.

MB: You run a series called Body of Art where you talk to other poets about the body and its role in their work. Are there any takeaways from your conversations with other creators that stand out to you?

KGT: Oh my gosh, there are so many takeaways, the biggest one being that no one teaches us how to love ourselves. I believe that there is a direct correlation between loving oneself and leading a fulfilling, liberating, and conscious life. We learn Algebra and the Periodic Table, but no one teaches us how to love ourselves. Every day I study and practice how to be kinder gentler toward myself. Like so many around me, I need more practice. It shouldn’t be such a struggle, but it is.

MB: Are there any words of encouragement that you might offer to a creative person who is struggling with an eating disorder? What you would tell someone who is on the verge of seeking treatment, but hesitating and doubting the value of their voice?

KGT: I would tell them that there is another side, but there will be a crossing over within yourself—you will need to decide that recovery is worth it. You will have to unlearn everything the world has told you. I would also shout from the rooftops: Write. About. That. Shit. I remember when “Where No One Says Eating Disorder” was published. I was flooded with messages from so many women saying things like, “You have no idea how much I relate to this.” Or “Thank you, no one ever talks about this.” Women ages 18-65 thank me every time I read a poem about an eating disorder.

Whoever needs to hear this: You are not alone. You are not your reflection. You do not need to be what the world tells you to be. Talk and write about what you are going through. There is freedom in language. If you need someone to listen, find me on social media. I’m here if you ever want to talk about the other side.

Kelly Grace Thomas is an ocean-obsessed Aries from Jersey. She is a self-taught poet, editor, educator and author. Kelly is the winner of the 2020 Jane Underwood Poetry Prize and a 2017 Neil Postman Award for Metaphor from Rattle, 2018 finalist for the Rita Dove Poetry Award and multiple pushcart prize nominee. Her first full-length collection, Boat Burned, was released with YesYes Books in January 2020. Kelly’s poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Best New Poets 2019, Los Angeles Review, Redivider, Muzzle, Sixth Finch, and more. Kelly is the Director of Education for Get Lit and the co-author of Words Ignite. She lives in the Bay Area with her husband Omid. www.kellygracethomas.com.

Madeleine Barnes is a doctoral fellow at The Graduate Center, CUNY. She is the author of You Do Not Have To Be Good, (Trio House Press, 2020) and three chapbooks, most recently Women’s Work (Tolsun Books, 2021). She serves as Poetry Editor at Cordella Magazine, a publication that showcases the work of women and non-binary creators. She is the recipient of a New York State Summer Writers Institute Fellowship, two Academy of American Poets Poetry Prizes, and the Gertrude Gordon Journalism Award. Her criticism has appeared in places like Tinderbox Poetry Review, Split Lip Magazine, and Glass: A Journal Poetry. www.madeleinebarnes.com.

Image via Quintana

On Beaches this Autumn

BY MONIQUE QUINTANA

I keep dreaming of beaches, not night dreams, but daydreams. When I teach from home on Wednesday mornings, my throat hurts because I’m not used to talking for so long anymore. I feel my entire self squirm every time I open a new tab on my computer and a new window opens.

I live in the Central Valley of California, in a town where the heat settles like dust, even on the first day of autumn. It is simultaneously rural and urban.

I daydream about beaches: Santa Cruz and Carmel by the Sea. I think about the last time I saw the sea. I think about how I scooped egg from its shell from my breakfast, packed neatly in a deep brown basket by the sea. I think about my dad buying me blackberry gelato after he and my mom split up. Before I knew what such a thing was and what I should be grateful for, my family setting food in my hands in the cold water breeze made me think of my death and shake.

I document everything I do on looseleaf paper—virtual meetings, missteps, canceled hotel reservations, and daily word count goals. I dream of beaches because they're so close to me. Past vineyards and rusted metal dinosaur statues. Past signs that say, Pray for Rain in large black letters. Two hours in either direction, and I'm there.

Unsplash/Canva

Join Our Witchy Book Challenge!

This autumn, join our witchy Instagram & Twitter book challenge!

WHAT TO DO:

To celebrate autumn, we’re asking you to take a picture of your fave witchy read (any book you love, or that you’ve written) and tag #LLWitchyReads on Instagram and/or Twitter so we can find and see it. Bonus if you share a bit about why you love it and tag the author if possible. Authors love the love.

TAG:

Tag as many pics with #LLWitchyReads as you’d like. Just be sure you drop the hashtag in the caption, not the comment. You can also tag @lunalunamag.

WHAT COUNTS:

Nonfiction, grimoires, magazines, academic works, fiction, poetry - it’s all welcome! And hell, even though we’re focusing on reads, you can tag podcasts too! We’ll share them as well.

You can share books you love, books you’ve written yourself (please do!), and books that are brand new or canonical or basically unknown. Folk magic, trad witchcraft, poems inspired by the archetype of the witch — it all works; this is pretty open!

WHAT IS THIS FOR?

Book love, basically. Community. Crowdsourcing recommendations. We’ll be sharing & reposting these pics of books simply to send them love — *and* we’ll be compiling some of them in an article published in October, which aims to share our community’s fave witchy reads. We’ll be linking to those books on @bookshop_org so you can pick ‘em up.

NOTE: For some reason, tagging hashtags in Instagram comments is not letting us see them, so you’ve got to take a pic and use the hashtag on IG in the caption. You can post to Twitter too!

We’re hoping to see new books, your fave classics, & works by BIPOC & LGBTQIA+ authors, who are underrepresented in the witchy world of books.

Let’s spread some magic. 🤎🍂🙏🏽

By Camille Brodard, via Unsplash

Poetry by Kiki Dombrowski

BY KIKI DOMBROWSKI

An Autumn Ceremony

Split yourself right down the middle:

celebrate academic and spiritual

collision on a Saturday afternoon.

Leave the ritual early

to make it to critique, arrive late.

Distract the class: release unbound

papers into the air, corners ripped

out for gum and phone numbers.

Have dirt on your hands from moving

stones, smell like a bonfire,

do not remove the moss and mulch

caught in the fibers of your sweater.

Let your hair be damp and wild,

weather is unpredictable and so are you.

When they ask where you’ve been

answer “An autumn ceremony.

Persephone gave me inspiration.”

Write a note about the hawk

that flew overhead with a snake

dangling in its talons. Render

metaphors about the snake

as an uncoiled noose rope. Keep chanting

in your mind: you are a circle,

within a circle. Shake a rattle.

Allow mugwort and tobacco to crumble

in the bottom of your book bag,

let it live in the creases of your notebook

which is full of assigned poetry prompts,

Mary Oliver quotes, circled stanzas

and underlined verbs. Keep your mind in ritual:

imagine the professor a magician, evoking

the spirits of stag, salmon, crow, and wolf.

Let the students close the ceremony

with a clap in each direction:

rituals and words are temporary

and so are you.

Vlad Bagacian, via Unsplash

Poetry by Dylan Krieger

BY DYLAN KRIEGER

the median

we couldn’t hold our breaths

the entire tunnel

so you told me your wish:

to be a different person

someone satiable

who knows how best to

scratch the itch of consciousness

well, little wide-eyed perfect puppy

i don’t know either

but i will dig my fingers

with utmost loving attention

into the skin behind your ears

for a million years

feed you bloodthirsty berries

from the lip of my paltry fountain

whatever doesn’t deserve you

i know full well, but i’ve worked hard

flown all over a dying empire

to tell you, to show you

the tragedy isn’t lost on me

i’m enlisting your balled spit

your half-lifted eyelid in orgasm

to write an alternate ending

pass a frantic notebook

back and forth laughing about

the private capacity for violence

in our passing glances over the median

eternally uncrossed between us

steering wheel shaking in both fists

like any moment we might

work up the worst courage

shatter the straight line

and kiss a cursed gear shift

into oncoming headlights

stay shelved

so many comrades in recovery, and here i am still mainlining dreams

as if across a crowded room, an angel might articulate my thought stream worm for worm

face-off too lush to get lost in the figures: ventriloquized incest, tin mood turned to snowmelt

when i hear you use apophatic correctly in a sentence, who you are is hard to miss

at the moment of corruption, the dial tone in your esophagus lasts forever

and all the germ-addled wounds are holy--that’s what the howling never tells you

explicitly, but it’s apparent whole forestfuls of woodpeckers get it, and we’re no different

thank the chaos for deciding to warm itself on our little spinning bonfire of lead

thank the hospital parking lot for reminding us childhood was canceled

from the start and yet it still feels fresh, mazel tov to our mutual collapse

i’ve been cosmically betrothed to one unmooring or another for so long wishing it were yours

i’ve been nine kinds of anemone, the plastic sixer rings skinning their predators

i’ve been the cliffs where anyone ignoring the weather’s warnings disappeared into the drift

but none of that would impress you, the usual terrors stay shelved

pages fingered to the point of crumble, and go ahead--i am helpless

to whatever feathers you next decide to pluck and spread

Dylan Krieger is writing the apocalypse in real time in south Louisiana. She earned her BA in English and philosophy from the University of Notre Dame and her MFA in creative writing from Louisiana State University, where she won the Robert Penn Warren Award in 2015. Her debut poetry collection, Giving Godhead (Delete Press, 2017), was dubbed "the best collection of poetry to appear in English in 2017" by the New York Times Book Review. She is also the author of Dreamland Trash (Saint Julian, 2018), No Ledge Left to Love (Ping-Pong, 2018), The Mother Wart (Vegetarian Alcoholic, 2019), Metamortuary (Nine Mile, 2020), and Soft-Focus Slaughterhouse (11:11, 2020). Find her at www.dylankrieger.com.

A Playlist for Fall

BY JOANNA C. VALENTE

As we fade into autumn within the next few weeks, I thought I’d round up what I’ve been listening to, with songs that celebrate and reflect on change.

Unsplash

Personal Essay As Bloodsport

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

Last night I happened on writer Deanna Schwartz’s Twitter conversation about selling trauma for a byline. Maybe you’ve seen it by now — it’s elicited all sorts of responses, which means it struck a vein. And it bled.

At first, I found myself feeling — what was it, exactly? — defensive. It’s my choice to sell my trauma if I want to! I don’t need a 21-year-old’s regret to muddy my experience. But I didn’t say that. I retweeted someone else’s eloquent response about the power of writing and then I logged off.

Of course, I kept thinking about it, in the dark, in bed. All those words, all that honesty, all that hunger to be a writer.

I remember those early writer days, swirling in some haze of poverty, confusion, and eagerness. Before MFA, writing was my heart language, and poetry was my truest identity. It alchemized the Me who’d been born of pain into some new Me, a transcendent thing. My work housed all of my secrets: the foster kid secret, the homeless shelter secret, the family addiction secret. It was my underworld, alit by passion. Poetry gave my suffering meaning, even if no one read it — and for a long time, I was alright with that.

Things changed when I was fresh out of MFA. I felt the pull to prove myself as a writer — to show that the $50,000 loan I’d taken out for graduate school was not all for naught. I was writing batches of freelance ehow.com articles for $3 or $5, and I was penning celebrity gossip blog posts about people I’d never heard of, for which I was underpaid. I never asked for more. Then I started this website. Writing became less of a thing that I was compelled by spirit to do and more of a thing I had to do. Or so I thought.

That beautiful byline? It was an illusory well in the desert. It was something other, better writers got to have.

Enter xoJane. Fuuuuuck. It was about 2013 or 2014, and I wanted that publication dopamine. I wanted to say, “I published this” and go about my day knowing the Internet housed a small piece of my soul and that everyone could walk past and glare at it, its maggots festering in publication glory.

I sold my traumas and ideas for, what, $50 a pop? I wrote honestly about not using birth control and got reamed out by family members who were “concerned for my wellbeing.” And then there were the “you’re a slut” emails (which, to be honest, trickle in every so often for no reason at all).

I talked about not having health insurance and being treated poorly at a hospital when I had a ruptured ovarian cyst. Although xoJane’s readership was mainly women, they were not interested in allyship. They had fangs and they were out for blood. Rather than compassion, most commenters fixated on the fact that I’d taken a hospital selfie. You’re not really sick. You’re lying. If you’re that sick, you don’t take a selfie. (I wonder what they’d think of the many chronic illness Instagram accounts today, which specifically document the experience of being ill).

This didn’t deflate me, though. This egged me the hell on. I wanted to drench these bloodsuckers in my pain, feed them the stinking abyss of my most personal wounds. Of course, this was a coping strategy, a way of justifying the fact that I’d put all of myself on the Internet to pay a sixth of my rent. I lived in a shitty apartment, mattress on the floor, three roommates — and every $50 was a $50 that could honestly change my life that month.

Eventually, I got a job at Hearst editing personal essays for The Fix, which solicited and pumped out personal essays to the various Hearst publications — mostly Cosmopolitan, Marie Claire, Good Housekeeping, and Redbook. This was probably the most stable and interesting job I’d had at that point, and I took it very seriously. In a sense, we were part of the personal essay pipeline, and I’d track views and clicks, curious to see what “performed” and what didn’t. We were sorely underpaying these writers to bare their souls — and if I could have paid them more, I would have.

In my heart, I believed that lending my editing skills to this platform was, in a way, helping these writers to bloom and grow through storytelling. I loved our writers. I gave my heart to their stories. I became their friends. But I’d be lying if I didn’t say that The Fix was part of the problem. It normalized bearing your grit and glory for very little pay — which often preys on the most vulnerable among us.

Publishing personal essays should not be a cavalier process; and these stories, in all their painful detail, should not be viewed as low-hanging fruit for clicks. Humans are at the other end of these stories, and we need to treat the process with humanity.

It’s not that I think Schwartz is entirely right, though, when she says, “Don’t sell your trauma and personal experiences at all! I sold mine for $300 and regret it. It's not worth the money and byline to feel like one essay is going to follow you around forever.”

I don’t think I’d say the same, even with my background editing personal essays and being burned at the stake online.

It’s that I hope more publications don’t exploit writers.

I think it’s a good idea to tell stories, to share your pain, and to normalize, through storytelling, the issues that society turns away from. Speaking aloud erases stigma and shame. It brings us together and creates a space of tolerance and support.

Personal essays are a sort of shadow work for the collective; they ask us to look within ourselves and cast the mirror out at society. It may be bloody, but ultimately, we all learn from it.

When I finally wrote my first personal essay about my foster care experience — for The Huffington Post — it was as though my albatross had finally moved on, taking a new form as something beautiful; my wound became my guiding light.

I was proud of this story. It led to a life of foster care advocacy, and even helped secured more bylines in The New York Times and Narratively. I believe that these stories helped me get book deals and create community. It gave me the writing life I always dreamed of (and, it turns out, was always working toward).

The difference between this piece and my work for xoJane was clear to me: I had taken the time to think about if and why I really wanted to publish this particular work. I had done it not under financial pressure. I was more mentally prepared for any backlash.

I can’t say I would have known how, when, or why to write my piece if I didn’t write all that garbage back then. I can’t say I would have become who I am without that.

Regret is a strong word. It’s a word that erases the climb, the journey, the necessity of discomfort.

I don’t regret any of it.

I think each writer gets to decide what feels right for them, and I don’t blame or shame any writer who feels the pull to publish. I know the power of money when you need it badly. And I know the hunger that comes with imposter syndrome and perceived competition and even self-competition. I also don’t think it’s fair to discount someone’s trauma if they had a bad experiencing publishing a personal essay. It’s personal.

The writing life is paved with strangeness, and curiosity and hunger often lead us down roads we might not have taken otherwise. Knowing how to bloodlet and for whom can help. But sometimes, you don’t know if it was worth it until you’re bleeding. And that’s okay.