A note on the submission: Word count: 600-2000. Essays and features preferred. Open to the right poetry. We can't wait to read your work. We're looking for the beautiful and haunted. Essays around the women who inspired you, the deaths that will never make sense, and the poisonous world of glamour and fame. To submit, see here.

Anagnorisis: Rebirth in Recognizing Your Truth

My arms yearned for these strangers, these men and women who walked in the shadows of their minds, feeling alone, feeling as though they did not share a thread with any part of society.

BY S.K. CLARKE

I am a firm believer that humankind requires food, water, shelter, and intimacy. After our stomachs are full and our bodies are kept warm, we desire the ability to be seen by another human being, to be heard and understood.

The pivotal moments in my life have centered on someone acknowledging my self, the oft-guarded soul that is tucked away from casual observers. Often the other’s ability to see me results in an enlightenment; a move from shaded reality to exposed self-truth. It is important to note that this truth is not always beautiful. We may not always be ready to accept the knowledge when it is thrust upon us by the seeing few, but it is honest and bears the weight of import, all the same.

Aristotle called this moment of self-reveal or recognition, anagnorisis. Often in Greek tragedies, the protagonist is in the dark about some aspect of their being. InOedipus Rex, Oedipus was ignorant to his truth: he had killed his biological father, married his biological mother, and gave her children.

In the case of Oedipus, his understanding of self, both what he stood for and who he was in society, came with the reveal of his paternity. But what’s interesting to note, is that the audience was fully aware of who Oedipus was long before the big reveal. The Greek people were a learned audience who had seen these stories play out several times before. The Oedipal legend was old and the men who had gathered to see the play performed would have known the ending before the characters on stage would live it. The reason they went was in order to see which playwright wrote the best version; which Oedipus would spark something new within the audience.

In this I find a unique formof anagnorisis that can only be found in art: a recognition of ourselves within the creative minds of the artist.

This movement of self-knowing from the external to the internal can often be found in the paintings, the music, the poems and stories that traverse time and space to enter our psyche through the crackle of a record player or the luminescence of a Kindle screen. Lyrics and verses and compositions and brushstrokes that navigate time, space, and language to knock at the cement fortresses within our souls and say, “Hey, I know you. You are not alone.”

For me, there has been a therapy in the words of Neil Young, Billy Joel, Damien Rice, and Ray LaMontagne. Their lyrics call to me, assuring me that someone somewhere has been a miner for a heart of gold and they, too, see me in all of my vulnerability, in the darkest places where my self lies hidden from the daily world. Their careful placing of syllables and emotions finally, exuberantly, pitifully give voice to all that I’ve been wanting to say, whether I knew it before or not.

I’ve found it in the carefully constructed words of authors Sherwood Anderson, Edgar Lee Masters, and Colum McCann, the dark despair of poetess Christina Rossetti, the inspirational instruction of Brené Brown. Within the isolated activity of reading, within their solitude of writing, I found a piece of myself. A communication between myself and an unknowable stranger who, reaching across distance, reaching beyond death, declares that they see me as I am and have shared in what I have felt.

As an educator, theatre artist, and writer, I often strive for this feeling of communion with my students, aiming for them to experience the power to be known. I hope that in the pages of dramatic literature, my students and actors can say, “In this, I see me.” I hope that they can find the human in all and through that magic of recognition, they will see themselves in Stella, Ophelia, and Everyman. And, perhaps, that Stella, Ophelia, and Everyman will cause them to see humanity within themselves.

Through this seeing, this knowing, a beauteous progress is made. Stagnation is held at bay and something entirely cosmic enters into our lives, whether we expected it or not.

As an instructor, I often do not anticipate this progress to be made in my own life. I have read Hamlet no less than thirty times. For me, the recognition has already been made and now I get to enjoy those steps in my students.

However, when I began directing a play this past semester, I was shocked to find that art still had more to show me.

The play centered on the cycle of abuse within relationships, both romantic and familial. A young wife is beaten within an inch of her life and through a series of increasingly absurd circumstances, is all but forgotten by the end of the play. Both she and the brain damage she possesses are erased from the family’s consciousness. The end of the play leaves the audience with the impression that the mental and physical abuse done to her is doomed to be repeated because it has never been fully addressed.

The artist in me latched on to the uncomfortability of this, the unfinished, unpolished ending that would remind us all that abuse knows no happy conclusion. I wanted the audience to feel embarrassed and uneasy, hoping that through some self-reflection they would see abusive behaviors in their own lives and after much thought, seek to eradicate them.

The future mother in me, however, felt that I personally needed to create a positive change in the community. I needed those who I worked in and around to know that this did not have to be the answer: that cycles can end and progress can be made to heal, to repair.

Encouraged by projects such as Humans of New York and PostSecret, the drama club and I worked together to place boxes throughout the college campus, asking for students, faculty, and staff to submit their “secrets,” their moments of abuse, harassment, or discrimination in hopes that, through the sharing, they would gain back a voice they did not feel they had.

Over the course of three weeks, we received over 150 responses. A few of the posts were drawings of a penis ranging in anatomical accuracy, but the majority of the submissions were heart-wrenching confessions of disease, abuse, insecurity, and desire.

“I feel like I have no true useful purpose and no true direction,” one submission said.

One confessed: “I forgot my little sister’s birthday.”

“I suffer from claustrophobia because my father used to lay on top of me,” exposed another.

Many revealed a long-harbored affection toward their best friends while others admitted to instances of infidelity. A large majority dealt with mental illness and some confessed the wish to end their own lives. One revealed that they were HIV-positive.

My arms yearned for these strangers, these men and women who walked in the shadows of their minds, feeling alone, feeling as though they did not share a thread with any part of society. Perhaps feeling that no one could empathize. No one could understand.

But I am writing this today to tell you I do understand. I do see you. I get it.

As I paged through secret after secret, I felt an unexpected click of recognition, a cracking of my defenses, a revealing of my truth. Many of the secrets dealt with rape. Many of those same confessions were also partnered with the statement that they had not told anybody, some for many years. Some had not mentioned their abuse until they had put it down on the slip of paper I now held in my hand.

I did not submit a secret to the project, but if I did it would read: I was raped and for three-and-a-half years I believed that it had been my fault.

I was staying at a friend’s family home in Italy. My friends and their family were all tucked away in their beds. I was downstairs being raped.

The guy was placed in my path deliberately. He was supposed to be a good flirt. A morale booster. He was not supposed to sit on my chest and force himself in my mouth. He was supposed to hear me when I said no. He was supposed to stop. He was not supposed to tell me that I deserved it, that I had led him on, that I had to finish what I had started.

I was not supposed to believe him.

But I did.

For years I believed that it had not been rape. It should have been more violent. I should have had scars. If it had been rape, I would have fought harder. The only rape that counted was the violent kind, not the kind that left me asking him quietly to stop, lest I wake anyone.

And so, I remained silent. I did not speak up about what had happened, did not utter the “R” word. I did not tell my friend who had slept upstairs. She had seen me flirt with him earlier in the night and I assumed she would think I was a tease. I didn’t tell my grandmother, though I called her the minute I got back to my apartment. I wanted her to hear my voice. I wanted her to fix what had broken inside of me. She had sounded tired when she had asked me if something was wrong and I chose not to burden her. She was going through chemo after all, and I felt that I was just another whore. I did not tell my mother who holds the key to most of my secrets. I was her good girl, not a sexual being who would be found in those types of situations. In my journals, I remained dumb. In therapy, I skirted the issue.

But as I sat there, holding the secrets of strangers in my hands, I felt the crack of anagnorisis, an understanding of my truth, of what I am and what I stand for.

“I see you,” I said to the anonymous submissions. “And you see me. You never deserved this. You are not wrong. You are not dirty. You are a victim.”

I am not talking about rape culture in America, extremely prevalent though it is. I’m not going to talk about how politics and the media make it difficult for victims to come forward, as was the case in Oklahoma and Brigham Young University. I won’t mention how rape is normalized in television shows such as Game of Thrones or how the porn industry seems to capitalize on male sexual aggression against often unwilling women. Nor will I mention that out of every 100 rapes, only two rapists will go to jail.

This is about finding those men and women who are afraid to view themselves as victims, those who feel alone in their stories of abuse or harassment. You may never hold 150 secrets in your hand, but you now hold mine. What I ask is that you see that unlike the me of three years ago, I now know that I never deserved what was done to me. I also never deserved to hold it within me in silence. I’ve acknowledged that no matter what I was wearing, no matter how I had been conducting myself prior to the incident, I had not given consent. I did not say yes and something that was precious within me was taken and tarnished. I was raped.

You, too, do not need to hold yourself in the shadows.

Whether you suffer from debilitating depression, whether you have experienced rape, sexual harassment, physical or mental abuse, or dependency of any kind, you are not alone. Your secret does not make you any less deserving of love, nor does voicing it admit any weakness. Through using your voice, by putting the words on paper, or sharing your story, you can begin the healing process.

The Aristotlean definition of anagnorisis is often associated with tragedies: King Lear realizes that Cordelia’s love is the truest only after she has died, Nora’s desire for self-knowledge causes her to abandon her husband and children, Bruce Willis discovers he’s dead in The Sixth Sense.

I would like to argue that there can also be a rebirth in the recognition, a happy ending. Only through the dead of winter can we prepare for the blossoming of spring. Only from the gravel can we build a foundation. Only from the ashes can the phoenix be born again. And only through recognizing your truth can we grow, learn, and heal as a whole.

S.K. Clarke is a writer, adjunct professor, and theatre director in Pennsylvania. She has earned her MA in Text and Performance from London’s Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts and her BFA in Acting at Philadelphia’s University of the Arts. Clarke is a writer of poetry, plays, and short stories focusing on the disintegration of small-town America, social and political injustices of minorities, coming-of-age and end-of-life narratives, and stories featuring complicated and strong female characters. She is currently writing her first novel which, she hopes, will touch on all of the aforementioned topics.

The Voices We Don’t Hear in Poetry Are the Ones We Need To

I was introduced to read a week ago at the Bowery Poetry Club…Cafe? Are they just BOWERY POETRY now? The particulars I’m not very familiar with because, surprisingly, it was my first time there, ever, in my 10 years in New York scribbling down the sideline chatter on the subway in the margins of my books, finding an acute little poem that comes from both the conversation and the words the conversation is transcribed next to. My introduction is prefaced withThis won’t make sense to anyone but me and she goes on to introduce me with two lines of poetry to which I respond at the mic, What do you mean? That totally makes sense. It’s always about me.

Read More

Seeking Submissions – Disability, Chronic Illness & Mental Health

BY ALAINA LEARY

As a disabled woman, these kinds of stories and perspectives are so important to me. I grew up thinking my existence was a burden - literally - and that I'd never be employed, that I had a higher chance of homelessness, that I couldn't make it, especially since I'm not only disabled, but also queer and middle class. I want these stories to be told. My parents were/are both mentally ill and disabled too. My mom couldn't drive, was visually impaired and stopped being able to work around the time I was born. But beyond my own family, I didn't know anyone who was disabled or ill. I didn't know it was a thing you could be and still be okay. That's why representation is so important and why I want to help publish some of those voices.

Editors Joanna C. Valente & Alaina Leary will be editing this special issue, so please submit your stories and artwork to them by August 1.

Poetry By Katie Manning

Back in America,

I read my professor’s poem that was shaped

like a breast on the page. He was edgier

than I thought. To this day, I regret not using

the words that came to me when I needed them.

Instead of Buying Another Cocktail, Shoot VIDA 10 Bucks...TODAY

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

Or just shoot them 10 bucks and get another cocktail.

Luna readers, today is the last day of VIDA's campaign. They're raised $10,000 so far – which will go toward their count, events, fellowships, and publications.

As editor of Luna Luna Magazine, and as a writer / editor for national and indie magazines, I - like many of you - got my start in literary magazines. I won't sugar-coat it: there are a lot of smarmy, egotistical white male dudebros at the top who want to keep brands old and dusty and free from new voices. We need to fight that power. I am glad VIDA was around to pave the way.

In many journals, especially top tier ones, women - women of color, especially - are published at a frighteningly lower rate. I wish I could say "times are changing" with absolute certainty, but we've got a way to go. VIDA is absolutely at the forefront of that by creating a necessary dialogue in order to elevate parity in literary art and create spaces for diverse voice. Obviously this needs to be applauded. And like Luna Luna, they're all volunteer. They're not sitting on mounds of money.

I think back to a time when, in college, a classroom professor suggested that the women in the class were writing in a "typically feminine" sort of way. As if colors and sounds were particularly womanly. Maybe they are? But the inference was that it was too girly, almost silly, like a young girl scribbling into her diary, unlike the apparently (?) more "real" poetry her male counterparts were writing. It wasn't easy to say that his implications were unfair or pandering or reductionist, or – at worst – sexist.

Those amorphous, slightly off-settling situations happen all the time and need to be defended against. The same is true for racial politics. We should be publishing diverse voices, not squandering opportunity or declining rejections or making it so that women and people of color aren't submitting at all. Nope. Support equality.

Review of Peyton Burgess' Fiction Collection 'The Fry Pans Aren't Sufficing'

“The Fry Pans Aren’t Sufficing” is a book I couldn’t put down. It’s a collection of short stories published by Lavender Ink Press, and a triumphant debut, by Peyton Burgess. These stories are gorgeously brought to life in three parts that weave together so naturally, I often felt I was reading about myself, or my friends, or some long lost best friend from my dreams. I believe in these stories.

Read MoreNY Theatre Guide

Ivo Van Hove’s 'The Crucible' Blew Me Away

This May Day was completely sans May, and instead a drearily beautiful pastiche of early autumn. The rain-splashed winds in conjunction with the rush of traffic in Times Square made my bell-sleeve floral dress sway gently against my thighs, and I clasped my jacket close to me, smiling through the mist. Sometimes life does imitate art, but I had no idea how fully this chilly Sunday would complement Ivo Van Hove’s rendition of Arthur Miller’s "The Crucible," now on Broadway at the Walter Kerr Theatre.

Read MoreImage via Flickr

I Read That Essay on xoJane After My Father's Suicide Attempt

It's not a blessing when mentally ill people die.

BY ALAINA LEARY

This is in response to xoJane's piece, "My Former Friend's Death Was A Blessing." You can also read about being a mental health ally and advocate as it relates to this piece here.

Earlier this week, my dad—someone with lifelong mental and physical health issues—tried to die by suicide and ended up in the ICU. He intentionally overdosed on his depression and anxiety medication. This was after several months of expressing suicidal thoughts to me and to therapists, and working with medical professionals in inpatient care.

About a month ago, my dad was refused any more inpatient care even though he insisted that he was still dealing with suicidal thoughts. He also received a denial letter for disability benefits, although he is dealing with early Alzheimer's, has had several surgeries for physical health problems, has been diagnosed with several serious mental illnesses, and has had worsening overall health since a car accident in October 2014.

Since then, he's been severely suicidal. Because he has a lifetime of mental health battles, including bipolar disorder and PTSD, this is not the first time I've worried about him attempting suicide. But it is the most upsetting time and it felt the most real. Over the last ten years or so, my dad has done nothing but try; this is his second serious attempt at getting the help he needs, including disability benefits and mental health care. In the last year or so, he's done nothing but try to fight for the resources he needs to survive, only to be failed time and time again.

Last month, doctors discovered a cyst on his breast while he was in the ER. When he later asked about getting it checked out, they repeated to him: "Are you here for your suicidal thoughts or for the cyst?" They refused to prioritize both; his physical health was put on the back burner because he was honest about wanting to die. Several times when he's been in the hospital, I've spoken with staff about his memory issues and cognitive health—all of which was ignored because they were focused on treating his depression. His symptoms of early Alzheimer's shouldn't be ignored, especially because some of his current medications make him even more drowsy and forgetful than he was before. He often forgets conversations we had just earlier in the week, and has had to be reminded about things we discussed. I've never been so angry with the health care system in my entire life.

This morning, I woke up after falling asleep crying about my dad's recent suicide attempt to find out about the now-removed xoJane essay, "My Former Friend's Death was a Blessing." I've never felt so angry at a writer. Yes, we're all entitled to our opinions, but some of those opinions should not be published, as Lisa Marie Basile details in her own piece about editorial integrity. I can only imagine how my dad, who feels useless and unworthy of life, would feel if he were to read that xoJane essay. It would be like a sign saying, "Because you can't take care of yourself right now, you're a burden to your family and friends, just like this writer says about her former friend. Your death would be a blessing, too."

Yes, we're all entitled to our opinions, but some of those opinions should not be published.

Those are thoughts suicidal people are already feeling. I know because my dad has told me. He loves me more than life itself, but he doesn't feel like he can do anything right. He feels like a burden to me and to others, and doesn't see any reason worth living anymore.

It hurts me so much to see that there are people out there who believe that someone like my dad, who can no longer take care of himself after over twenty years of fighting, are "beyond help" and that death is "inevitable." Just because someone deals with serious mental health issues doesn't mean we should give up hope and give them a reason to give up. It's not a blessing when mentally ill people die.

The individual situations are different, obviously. Leah was a young woman and she spoke of schizoaffective disorder. Unfortunately, we don't really know her. We know only of her what the writer chose to tell us through a voyeuristic, cold, empathy-free lens. My dad is middle-aged, physically disabled, and has a history of unhealthy coping mechanisms, like drinking and being a workaholic. But at their core, they're not so different. Neither could take care of themselves completely on their own, and both needed support. And in Leah's case, she failed to get that support, and even after her death, instead of being mourned, she was turned into a sensationalist headline.

Just because someone deals with serious mental health issues doesn't mean we should give up hope and give them a reason to give up.

My dad is mentally, physically, and cognitively ill right now. He needs help taking care of himself. He doesn't need self-care; he needs community support. It's not always an easy task, and for my own health and well being, I can't be all things to him at all times. But the one thing I can always do is reassure him—and any other mentally ill person reading this—that there is hope, and that they're loved. And they deserve to live, even when it may seem impossible.

Alaina Leary is a native Bostonian studying for her MA in Publishing at Emerson College, and working as a social content curator at Connelly Partners. Her work has been published in Cosmopolitan, Marie Claire, Seventeen, Redbook, BUST, Her Campus, AfterEllen, Ravishly, and more. When she's not busy playing around with words, she spends her time surrounded by her two cats, Blue and Gansey, or at the beach. She can often be found re-reading her favorite books and covering everything in glitter. You can find her on Twitter and Instagram @alainaskeys.

4 Ways You Can Be a Mental Health Advocate & Ally

What does being a mental health ally and advocate mean? It means having empathy for others, raising awareness around mental illnesses, and breaking down negative stereotyping. When we write about mental health, especially when we write personal narratives about people we know, it is imperative to be empathetic, and to look at all the angles—to approach from a “human first” point of view.

Read MoreEditorial Integrity & xoJane's 'My Former Friend's Death Was A Blessing'

I work in digital media. I read and edit personal essays every single day. The pieces I publish tend to be vulnerable, insightful, and quite nuanced. I am proud of the voices I edit – and I'm proud of the role I play in that process. But let's be honest: I would be quite the liar if I said I wasn't well-versed in clickbait. For many publications – and I happen to edit for a dozen of them – clickbait is synonymous with paycheck. It's a sad state of affairs, but we must give the people what they want.

Poetry: A Calendar, A Cycle by Dylan Smeak

In August, she feeds summer figs to spring rabbits. From a sweating lawn-chair, she watches the waxing moon in the mouth of midnight reflect in the curve of her kitchen knife, shining bold and out of place. She drops the sticky bruised pieces to the rabbits, their shapes sinking into uncut grass as they feed. She watches their bodies turn slow and thick, their stomachs coated violet with shreds of sweet fig. In September, six fledglings fall from her front lawn dogwood. She takes their small bodies into her hands, brushing away the fallen nest while admiring the pieces of cigarette and onion bag weaved between pine needles. In her backyard, she digs six pits in the soil of her herb plot. In the evening, she sits on her porch smoking cigarettes while she waits for the mother's return. The mother never comes. Unable to fall asleep, she walks to the shattered nest and places six cashed cigarette filters at the base of the tree; an offer of trade she hopes the mother will accept. In October, she pours a boy a bourbon soda, stirs the spirit with a spent sage stem. In the oven, a rabbit roasts–its skin soaked in herbed butter and crisping by the second. She watches the boy's hands choke his glass like a neck. She imagines these hands around the suspension threads of her throat– the buds of her eyes blooming wide beneath an understood brutality. Her becoming destroyed for some eager mouth. For now, she waits in the heat of her kitchen. A maven of opportunity constructing unseeable scaffolding, its beams spiraling upward through the roof, rupturing the night and barreling out into lord knows what.

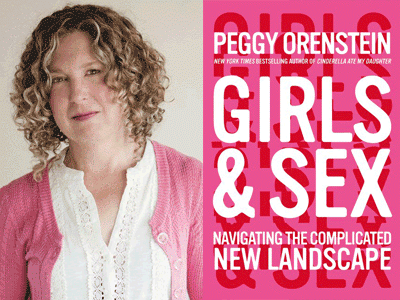

Read MoreInterview with Peggy Orenstein on 'Girls & Sex'

Much has changed between my generation and the time period my mothers generation terms of technology, politics, gender norms, but most notably with dating. In her new book, Girls & Sex, journalist and mother Peggy Orenstein interviews over 70 women and discusses sexuality with experts to reveal some shocking (and often overlooked) truths about the reality of girls and sex.

Read MoreFiction: Small Town Girls by Lacey Jane Henson

She leaned forward a little and it wasn’t until then that I really got scared, imagining her in this new room in my new house, those teeth tearing my guts. I opened my mouth to scream for my mom and dad but right before I could, she vanished, just as if she’d never been there at all. I made a small sound, like the one you make at the doctor’s, when they put the tongue depressor in your mouth. I blinked: nothing. She was still gone. I bit my tongue until I tasted blood—proof I was still awake. I expected something more to happen, and stayed awake a long time, waiting. The girl stayed gone.

Read MoreSea Foam Mag is a Place for Different Mediums & Diverse Voices

Art is so subjective and I really want to provide a platform that offers a diverse look at different mediums and formats of expression, with a focus on traditionally oppressed or under recognized groups.

Read More