If you hadn't guessed by now, you probably guessed I like to read a lot. Since I take the subway wherever I go, it actually frees up a lot of time for me to read, which I'm grateful for. Over the past few months, I've gone to a lot of readings--including AWP--where I was able to get a lot of new books.

Read MoreWriters Real-Talk About Getting an MFA: Diversity, Debt & Community Support

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

The MFA debate can get pretty silly, no? Is it pointless? Is it overpriced? Does it regurgitate the dreaded borg-hearted MFA voice? Maybe, maybe, and maybe. There are just too many variables to consider.

I used to daydream about perfectly articulating my disdain for the MFA. It’s been four years since graduating, and the reason I disliked my program has become clearer and clearer to me. It took me four years of separation to see it, and I'm glad I didn't commit opinion to paper before now. Where I used to solely blame the program I can see my own flaws. I wasn’t ready. I didn’t take enough time to learn about myself before MFA. I was in a relationship that affected my concentration. But it was also not what I expected, save for a class or two. I didn't feel challenged, and I felt like the stronger writers suffered at the hands of people who weren't sure what they were doing there (paying money to kill time, essentially). I’m also in debt – tons of debt, debt that no one talked to me about, and debt I imagined I would magically – or easily – pay off.)

Getting an MFA is a personal decision, one that is dependent on internal goals. Some people want community, while others want to be able to teach. Some people want to put off working. Some people work 9-5 through their MFA. Some people breath writing. Some people think of poetry as a hobby. There are so many things pre-MFA candidates should think closely about – how the program will serve them, how the program may harm them, and how others in the program play a part in the whole.

I asked a group of 39 people on Facebook what they wished someone would have told them before they went into MFA, and it started the conversation you see here.

Is it worth it?

“Stay true to yourself, be prepared to have your heart ripped out, and find people whom you can emulate and who will encourage you. Take what you want and leave the rest.”

“Follow your guts. In my case, my MFA was one of the best, most genuine things I've ever done for myself, and it's worth all the crazy debt.”

“Don't expect to be taught how to write. That's not how it works.”

““It doesn't usually lead to a job, a book deal, teaching or anything realistic.”

“Don’t do it.”

“With the MFA, you get what YOU put into it. The degree itself doesn't mean very much, but if you take your work seriously, write like a madwoman, give it your all, it DOES pay off. You have to give yourself permission to do this and to do it with your gut, heart, and head. You'll work long hours, yes, spend them writing and reading and networking and falling in love with the craft and the process. I started my MFA in 2007 and graduated 2011. I needed time to "steep" and mature, so don't beat yourself up if you need more time, too. I grew immensely as a writer in those years, but it wasn't just because I had inspirational mentors or fantastic feedback or a wonderful environment or even time and space (I worked full time throughout to avoid debt). I grew as a writer because I put in the long hours and hard work. It takes gumption and this crazy idea of believing in yourself.”

“Other people don't always take it seriously, and sometimes that can feel discouraging. I think for myself, I had to realize that this was my work and my experience, and it took me time to come to that conclusion as a writer. Sometimes, other students wouldn't give decent feedback. And honestly, sometimes I was guilty of that too. Ultimately, it's about making the best of your environment you're in, and figuring out how to thrive and get the most out of it as possible. It's a personal thing. And once I figured that out, I was much better off.”

Should I focus on publishing during my MFA?

“I think my MFA mostly paid off in me learning how to write, how to take myself and my craft seriously. You can certainly publish without an MFA, but I was in an environment that encouraged and celebrating submitting and publishing. So there was that motivation. It felt awesome to tell my advisor each time a piece got picked up! My mentors would often suggest places to send my work, too, so that helped. But it really wasn't about publishing. It was about being a part of a writing community that was supportive (for the most part), encouraging (for the most part), and to have a group of readers to challenge me and my work to develop and get better.”

"I won't lie. It fucking bugged me that very few people in my class knew how to submit to literary journals. By the time you get to Masters level you should have a clue, I think. You're coming in to hone your work, not learn to read a submissions page."

“People get obsessed with ‘having a book.’ Publish when it’s right. Not because you’re in or post-MFA.”

“As far as getting published/sending work out, that was not something that was stressed or even talked about much in my program.”

How important are having mentors and support?

“You aren't necessarily going to meet your mentor because many of the professors are juggling multiple classes/jobs/writing. Which isn't personal, of course, but because many universities and colleges don't hire these professors/writers full time, everyone's priorities and energies are stretched too thin. And that was highly disappointing for me because that's primarily why I went.”

"As I was finishing the program, sometimes I felt like another mentor in the classroom, which helped me develop my own teaching abilities. I think this helped me become a more understanding teacher, too. I also learned a lot from my peers who were more advanced than me. I was able to see the difference between my peers who were thriving and those who were floundering. I wanted to thrive, so I did what they did and made friendships with them.

“[The mentorship element] is especially an issue nowadays, with many writers teaching in multiple programs. And with it being a 2-3 year thing, even one sabbatical can mean not connecting.”

“That it's okay to disagree with (and ignore) a mentor's critique/edits if they don't know what's best for your work. To know that sometimes your mentor DOESN'T know what's best for your work, and to trust your instincts (and peer review ) in those cases. Especially peer review...at the end of the program, you're all going to be MFAs, which is often the same degree held by....yep, your mentor.”

“My conversations about my poems during the semester were all one-on-one with my mentor. So much better than the round table discussions during undergrad. We had workshops for a few poems during residency, but the bulk of my poems were discussed only with my mentor.”

“If you get paired with a mentor with whom you don't work well, the semester might end up being a bust. I saw that happen to a couple of folks. I was fortunate that it didn't happen to me, though some of my semesters were more productive than others.”

“I had lazy professors sometimes. I remember one poem I wrote and submitted for a class that I never got any feedback on and numerous that got tons of feedback. It sucked sometimes. Other times, I'd get feedback that was clearly the professor wanting my work to be something else than I intended. You have to deal with a lot of imperfections because no program is going to be perfect. You have to seek out good feedback from writers you trust. Again, that's sometimes going to fall on your shoulders. It took me 5 years to realize that. It ultimately comes down to being responsible for your own learning and growth. There are no mentors who are going to come in and do the hard work for you, no program or environment that's going to magically make it all come together. To be a writer, that's in your lap and your lap alone. On that note, we all need different things to thrive, so it's a matter of knowing yourself and knowing your own personal needs as a writer and human being.”

“Other writers can be mean and aren't often supportive. You have to find your own support and remember that in the end you are competing, so some people are just going to be mean. Don't take it personally. Literary bullying exists but can be shut down.”

“We also had a very new professor who tested her class out on us and we were all unhappy to have wasted a semester on that – though the learning was strong – the class itself was all disjointed. The class after us got the benefit of our comments and ideas - we never got anything (even thanks)."

What's the talent pool like?

“MFA programs admit students based on potential, not based on current level of talent. I had this expectation that I would see strong writing and receive excellent feedback from my peers and it was initially frustrating for me. I had to learn on focusing on the quality of my own work rather than worrying about the quality of others.”

"A lot of copycats."

"In an MFA program, you might not be with a group of writers at the same "level" as yourself, but I think there's something to learn from that experience as well. "

“I think a lot of people end up doing the MFA right out of undergrad, or almost right out of undergrad. For a lot of them, it ends up being a really expensive way of "finding yourself."

“In my experience, in terms of the larger gestalt of the whole thing, it created a sort of giddy, youthful culture of self-exploration. That ended up being both really positive, and sometimes really negative. But in terms of the workshop culture, I often felt as if our discussions were just total anarchist free-for-all. Like anyone could say, "I feel like…" or "This doesn't work for me," and not actually offer a craft-based explanation. I'd often walk away from workshop discussions more confused than I went in. On the other hand, in retrospect, that made me a stronger writer, because I had to learn to really trust my gut.”

“Impostor syndrome is normal. Learn from the writers you're jealous of, borrow their techniques and see if they work for you or not, don't waste time being jealous of them."

[Editors note: Experiment with voice. DO NOT PUBLISH WORK THAT MIMICS PEOPLE'S WORK.]

“I was 20 when I started my MFA. I was too young. My work was undisciplined and really unfocused. I didn't understand what it meant to be a writer. I actually started the program in hopes of earning a masters degree so I could teach the "good" high school English classes, but my goals changed and matured as I worked my way through the program. I began to see writing as a part of my identity rather than a means to an end. Again, I grew immensely, and I think it was mostly personal.”

How important is the critique element?

“I have an MFA from Hollins University. It's very difficult to find people who know how to critique. A good critique requires the reader to understand what the author is trying to accomplish and then offer suggestions to help, placing it within the larger framework of similar pieces. Many workshop readers focus on what they want the piece to be, rather than what the author is trying to accomplish.”

“Many others admitted may have never been in a workshop before. There is a lot of variety in level in terms of writing and critique ability. Form your own writing circle and get out in the community with non-academic writers to keep yourself humble!”

“I think a good MFA program will help hone those skills – how to critique and how to be a better reader. Writing reviews, I learned, was one really fantastic way to go about doing that.”

“Don’t freak out if someone in your class always gets fantastic feedback while the rest of you are confronting your demons. That has a lot to do with the aspirations of everyone else being pinned on one style, and obviously, the harsh critique is better for you, like kale or broccoli. Doesn't mean you enjoy it.”

“Pick your friends and thesis group carefully and as early as possible. Keep the critiques as honest as possible and try not to fall for the star writer and fawn with the rest of the class and professors. That helps no one.”

Did diversity and class issues affect you?

“I often felt alienated coming from a poorer background, and class issues definitely played a role in the program.”

“There were very few non-white students during my three years, but we were pretty evenly split between men and women (the poetry students were mostly women). The majority were way under 50. At 29, I wasn't considered one of the "kids."

“The majority of students were under 25 and it was a big dating game in the first year.”

“I only had white men as poet mentors (profs and visiting writers). I got to work with a woman with nonfiction briefly. In workshop, it was overwhelmingly white. The few POC students expressed feelings of isolation – and often, these students had horrible experiences in workshop with people not understanding the work or what the author was attempting.”

"I felt like I was alone. The majority of people were rich white kids."

What about low-residency programs and finding time to write?

“Do plenty of research about full vs. low-residency programs. When I was applying (around 2010) there seemed to be a stigma attached to low-residency in that you could never get the same attention and access to faculty help that you could from full residency. Looking back, I don't think that's true–you're going to be doing 99% of your writing and revising on your own in any case.”

“It used to feel like a low-residency program added an asterisk to your degree. But now, low-residencies can be an excellent option, in some cases offering access to faculty that might otherwise be out of reach. The residencies that anchor each term, at least in our program, are an outstanding resource.”

““I'm not sure what the answer is in work vs. writing, because it's really STILL something I'm trying to figure out. I wrote during my lunch hour, after coming home at the end of the day, during the weekends, etc. Almost every ounce of m spare time was spent reading, writing, researching and submitting. I was kind of obsessed.”

“Be careful of "free ride" rhetoric if it really means underpaid teaching job that prevents time for outside employment. I worked full time through my MFA at a nonprofit, but that ended up being a better professional set-up than if I'd gone with a program that offered full funding in return for teaching undergrads”

“Kids, job, husband – full time wasn't an option for me. Though if I'd known about fully funded programs (never heard of grad school without debt, until after my MFA), I might have found a way to make it work”

How awful is the debt?

“Unless you have parents paying, you are fucked. People don't tell you that. And then you wonder why some MFA kids breeze through while those of us work jobs and pay debt and have little time to write."

"You will be in debt for decades afterward. That's a high price to pay for what essentially comes down to confidence, perspective, craft, and community. In retrospect, for me, it was worth it. I would not have been able to build those things on my own. But I don't think it is worth it for everyone.”

“Don't pay for it. Get a free ride, or as close as you can. Do your research! I had an almost-free ride—but I still didn't have nearly enough to live on. It was the loans I took out for living expenses that ended up fucking me over.”

“I thought taking out the max amount of government student loans to live off of was probably a bad idea…but it turns out it was a completely idiotic idea.”

“Yeah I was told that adjunct live was rough but I had no idea that it is completely unsustainable.”

“Find out if they offer teaching grants or editing grants, also? Some might offer a handful, but those might be really hard to snag.”

“I'm faculty at a BFA program and give a talk on this each Fall. My first bit advice is not to do an MFA because you want a teaching job. I speak frankly about the job market and over-saturation. For those still interested, I urge them to look for well-funded programs and consider both the size of the program, TA/RA opportunities, and how the faculty/coursework line up with their writing goals. Ultimately, I tell them applying is a part-time job, and it's worth it to really do the research. I also suggest they consider geography in terms of cost of living. I do my best to help them navigate the field and suggest some programs that people I know have had terrifically nurturing experiences with.”

“You will be in debt until you are old and grey and may not even get any teaching experience - make sure you ask about that (if you want to teach) and always look for a program that offers a full or partial ride with teaching opportunities.”

How do you stay true to your voice?

“The MFA Voice is a myth; it’s not all-permeating, but there are trends, and they are obvious.”

“My worst and best experience happened in a workshop -- I am a feminist poet, and my early work interrogated sexuality as a means to talk about gender inequality and sexism. Well, one day, I read my poem aloud in workshop as we oft do, and a male student blurted -- "Katie, why do you only write about sex? I mean, there are other things to write about, or is that all you think about?" And everyone laughed, including the professor, who agreed with him. I felt so embarrassed -- they were missing the entire "point" of my writing about sexuality. We were then in the same class studying a poem that had sexual themes, the same student blurted out -- "I bet Katie wrote this poem." So embarrassing. I could have stopped writing sexy poems. I wanted to. I wanted to curl up under my desk and hide, but in the end, I learned from that shitty experience to toughen up. I learned that people aren't always going to "get" your work. I learned that it's ok to have obsessions and to write about them obsessively. I kept writing about sex! That day in class I learned so ridiculously much about the way the world works -- about shame and about gender roles and about being strong regardless of it all.”

Do you get burned out?

"You may get burned out and not write a line for two years afterwards, and if you do, it doesn't mean you'll stop writing. Seriously I wish someone had told me this. I felt like a complete and utter failure when I just did not want to write - actively had an aversion to it. I'm back in the saddle, and all the happier for it, but knowing that was a possibility would've made a huge difference!

“I was totally burned out for a couple of years, and really resentful about the whole experience. I did not realize how much I had learned in my MFA, or how rich and nuanced my education had actually been, or how ultimately positive it ended up being for my career, until like three years later.”

“I worked the entire time during MFA (9-5) and it felt like I was just exhausted afterward. Ironically, having space gave me my voice back and revived my love of writing. The MFA took something from me, something that prevented me from really writing well. It was the focus on popularity and fitting in that prevented me from blossoming. This is an issue. But after getting away from all those too-cool-for-school kids I really found my way as a writer. But I did learn how to talk about poetry.”

Lisa Marie Basile is a NYC-based poet, editor, and writer. She’s the founding editor-in-chief of Luna Luna Magazine, and her work has or will appear in PANK, Thrush, Ampersand Review, The Atlas Review and others. She's also written for Hello Giggles, Bustle, Bust, The Establishment, The Gloss, xoJane, Good Housekeeping, Redbook, and The Huffington Post, and other sites. She is the author of Apocryphal (Noctuary Press, Uni of Buffalo) and a few chapbooks. Her work as a poet and editor have been featured in Amy Poehler’s Smart Girls, The New York Daily News, Best American Poetry, and The Rumpus, among others. She currently works for Hearst Digital Media, where she edits for The Mix, their contributor network.

Witchy World Roundup: May 2016

These are interviews, articles, and pieces of literature that I've read in the past month.

Read MoreInterview with Performer Eliza Gibson: 'Lesbian Divorce Happens'

Eliza Gibson knows how to write--and perform. She is currently performing in her newest performance piece "And Now, No Flip Flips?!", which draws from her personal life in a poignant and funny way. She uses humor to tell her story--which is one that is both common and hardly written about--divorce. In Gibson's case, she is portraying what divorce looks like for two women, which has been routinely ignored by mainstream media and culture. This is a huge step for the LGBTQIA community, and it's an amazing performance.

Read MoreAn Apology Letter to the 8-Year-Old Girl at the Salon

I don’t know your name, little girl, but I do know that I owe you an apology. I would have given you one in person, but I was feeling too ashamed. Do you know this word, shame? I hope you don’t. I hope you never do.

Read MoreFlickr

I’m Not Your Inspiration Porn: On Being a Disabled, Queer Survivor

I'm a queer, disabled survivor, but I'm not your "inspiration porn."

BY ALAINA LEARY

I remember the first time I heard it: “You should be so proud, after all that you’ve been through!” I was 11 years old. It was within a year of my mom’s sudden, unexpected death, and I’d been given several awards and switched into the Honors programs halfway through sixth grade.

When I first heard it, there were so many thoughts running through my head. I was only a kid, and I really didn’t know how to react to compliments yet. I heard that I should be proud of my accomplishments, but I also heard that pride was based on the struggles I’d survived. Would I have been showered with these accolades if I were just a normal 11-year-old?

I guess I’ll never know. Since day one, I’ve been part of the other—marginalized groups that are frequently discriminated against. I have several interconnected sensory and developmental disabilities—autism, with comorbid dyspraxia and sensory processing disorder—that can be hard to explain to other people. I have no sense of balance, so I can’t ride a bike, walk in a straight line one foot at a time, or walk the balance beam. My brain shuts down if I experience sensory overload, and it’s very difficult for me to learn faces, geographical directions, and, for whatever reason, the parts of a sentence.

Because I’m disabled, from the beginning, I was always going to be subject to inspiration porn—either that or its direct counterpart, people feeling sorry for me or my caregivers because of the things I can’t do.

But I never made it to the point where I was somebody’s disability-specific inspiration porn, because my story became so much more than that. My story became one of survival, perseverance, and following your dreams. And people loved it.

When I was 11, my mom died unexpectedly, and my world was thrown into chaos. At the same time, I was exploring my sexuality, and came out as gay to friends and family. I was bullied relentlessly by my peers for years as a result. In early high school, I was the victim of sexual assault three times. In college, one of my best friends died in a car accident, and I was raped at a college party. Along the way, I’ve also lost aunts, uncles, grandparents, family pets, and have dealt with my dad’s worsening physical and cognitive health.

“Inspiration porn” was a word coined by the disabled community, and it’s a word that I sometimes use to describe myself. The people who are tokenizing me don’t always know that I’m disabled, but they might, or they see the symptoms but don’t recognize that they make up a disability. I've taken the word to mean, in my personal experience, that people use my story to be inspired because of what I've accomplished in spite of hardship. In spite of disability, in spite of being marginalized, in spite of so much loss at a young age.

Being inspiration porn does a funny thing to your psyche: in equal parts, you’re so proud to be such an advocate for the communities you’re a part of, and you’re happy to inspire others who may be struggling; but you’re also thrown off, because you’re so much more than an “inspiration because of your circumstances.”

When I first started receiving these compliments, I was only a kid. After years of one-on-one tutoring, special education classes, and physical, speech, and occupational therapy, I made the Honor roll. I got into Honors classes. I got the top awards for best grades in English and Science. I read more books in a year than anyone in my class. I was on TV. I was in the newspaper. I wrote a book, met the mayor of my town, and got an award for it.

And what did people see? They saw the story. They saw me as a headline. Here I was, seemingly “formerly disabled” girl who failed English class, who barely passed the second grade, who couldn’t ride a bike or walk up the stairs one foot at a time, getting straight A’s.

Somewhere along the way, being everyone’s inspiration porn became a part of my identity. I heard it so often that I went along with it—and that was easy. All I had to do was keep up a string of constant accomplishments, each one slightly more impressive than the last, and make sure they were publicly known. In more ways than one, I became almost addicted to the rush that came with the slew of compliments.

But giving in to the inspiration porn doesn’t allow me to fully be myself. I am disabled. I am queer. I am a rape survivor. But there is so much more to those parts of me than my ability to accomplish “in spite of.”

I am disabled. I am queer. I am a rape survivor. But there is so much more to those parts of me than my ability to accomplish “in spite of.”

People mean well, and they sometimes get it right. My cousin and I have a special relationship, in that the first thing she always says to me when we hang out is, "I'm really proud of you. But I would be proud of you no matter what." She congratulates me on my work and my education, but says that her love and pride are not contingent on those markers of success. They're unconditional.

It's something we don't talk about often. Not in the space of marginalized groups, but not in majority spaces either: the radical idea that you can be proud of someone and love them beyond the way they're meeting societal standards of success, like education, work, and professional achievements.

It's probably why I'm so bad at taking compliments. Just last week, I was distinguished as an alumni speaker at my alma mater, and it involved being showered with compliments both before and after my speech from faculty and students alike. Part of it is because I've adopted a lifelong growth mindset; the idea that my work and I can always be improved. But part of it is also because, in the back of my mind, I'm wondering: "Would people be proud of me if I were a queer, disabled survivor who wasn't published in Cosmopolitan, earning a master's degree, and working full-time?"

That's not because the people in my life make me feel that way. It's because I've internalized the idea that being disabled and a survivor are bad, and they're things to overcome and leave behind. It's only in recent years that I stopped feeling the same way about being queer, and a lot of that has to do with shifting the way we talk about LGBTQIA people: not solely classified as burdens or inspiration, but as fully-actualized people. I'm starting to see the same mindset shift with disability and mental health, but there's so much work to be done and conversations that need to happen in a public space. A huge step is adding well-rounded representation in the media, so people have a window to look through; to see that a disabled person or a survivor is so much more than just a label.

Being a disabled, queer survivor isn’t something I overcame to succeed. Part of the reason I’m doing so well—living my life, loving it every day—is because I’m disabled. I may not be able to diagram a sentence, but I can spot copyediting mistakes just because they don’t fit the patterns I’ve seen across hundreds of thousands of words I’ve read. Because of my disability, I have the intense ability to hyper-focus on something I’m doing for several hours at a time without interruption. I’m also very adept at picking up new tasks and creating, and it’s because of my disability that I was able to teach myself Photoshop, InDesign, HTML/CSS, and JavaScript.

After my mom died, I threw myself into being busy. I’d always been a creator—someone who wanted to make the things that didn’t already exist, and who was very hands on in her approach to creating. Being busy distracted me from being sad. During the nights when I was home after school and mourning, I threw myself into writing a book about losing my mom, and then producing it: creating the layout, setting the typography, designing the cover, and printing and binding it.

Being busy provided reassurance for me when I went through tough times. I lost my mom, so I learned how to code web layouts and design graphics for them. I was sexually assaulted, so I threw myself into photo editing and professional photography. I was bullied for being queer, so I moderated online social spaces for LGBTQIA youth. These were all skills I continued developing, and I owe a lot of my success to living through these experiences.

When people reduce me to inspiration porn, what they’re often missing is how integral my disability, my queerness, and the things I’ve survived are to the person I am today. My success and my struggles are all wrapped up together, and my identity can’t be reduced to “moving past” or “overcoming,” when the very reason I’m so passionate and driven is because I’m there, in the trenches, living life as a disabled, queer survivor.

It’s not in spite of what I’ve gone through that I succeed. It’s because of.

Alaina Leary is a native Boston studying for her MA in Publishing and Writing at Emerson College. She's also working as an editor and a social media designer for several magazines and small businesses. Her work has been published inCosmopolitan, Marie Claire, Seventeen, BUST, AfterEllen, Ravishly, BlogHer, The Mighty, and more. When she's not busy playing around with words, she spends her time surrounded by her two cats, Blue and Gansey, or at the beach. She can often be found re-reading her favorite books and covering everything in glitter. You can find her on Twitter and Instagram @alainaskeys.

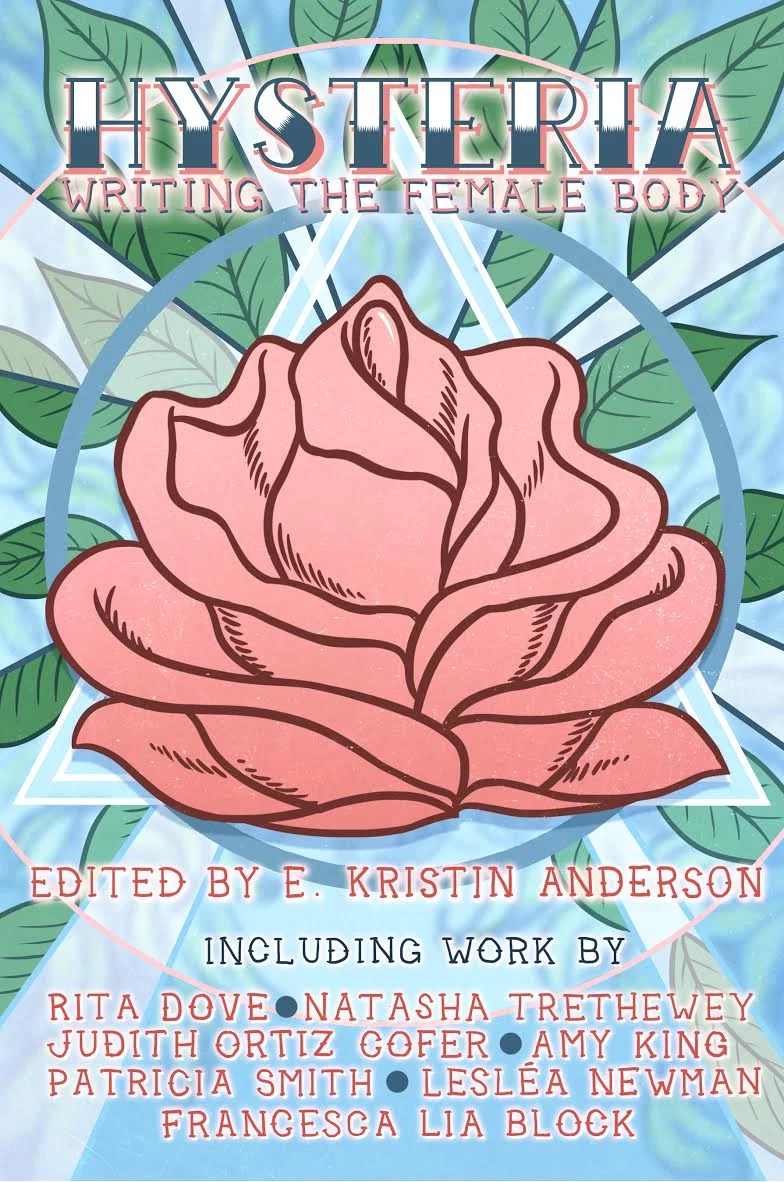

The Cover Reveal for Lucky Bastard Press' Hysteria Anthology

Check out the exclusive cover reveal of Lucky Bastard Press' HYSTERIA anthology + enter to win a copy & bonus swag.

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

As both editor of Luna Luna and a contributor to Hysteria (an anthology of writing by female and nonbinary writers about their biology and anatomy and experiences with the body) I thought doing a reveal of their cover would be a great way to create a dialogue about this amazing collection of works. When E. Kristen Anderson presented the idea, I thought Luna Luna would be the perfect home for this.

Want your own free copy? Here's how!

1. Tweet or post a link to their fundraiser (or just write a super cute supportive tweet/post about the book).

2. Leave a comment below (with the link to your social post) + your email (so we can contact you!)

3. We'll pick a comment at random and send you the anthology, along with E. Kristin Anderson's gorgeous Lana Del Rey-inspired poetry collection (I've read it, blurbed it and adore it).

LMB: Who is the team behind Hysteria?

EKA: Allie Marini and Brennan DeFrisco gave me the platform to do this anthology when they green-lighted the project at Lucky Bastard, but it’s basically been me and the contributing authors. Allie and Brennan definitely helped with soliciting some fine voices I hadn’t heard of, and have been a great support, so I don’t want to be like, oh, hey, this was all me. But in a lot of ways it was. And it’s been both intense and rewarding.

I think what Hysteria does so well is take a topic that is hard to write about successfully and inclusively (the body and notions of femininity, in many cases) and make it subversive; it's envelope-pushing. What sort of bodies did you want to include here?

It kind of started with me writing erasure/found poetry from tampon packaging. I’m not even kidding. And Allie and I got to talking about a tampon/period anthology and we expanded the idea out to other body-related themes. We went from there.

I certainly did want to push the envelope. But what I found interesting is that some poets that I thought would submit told me (before later submitting and being selected for the anthology) thought their work wouldn’t be edgy enough. And my answer to everyone asking “would my work be suited for HYSTERIA?” was “there are many ways to experience the female body/being female.”

So I wanted lots of bodies. Including nonbinary and trans bodies, which was a little harder because I know that many of these writers have been excluded from this type of project. We went looking, and we found some amazing work.

Tell me a little bit about what spoke to you when selecting content?

Diversity of topic and voice was really important to me. I wanted—like I mentioned above—lots of experiences to be represented. There was a point at which I think I posted on my original call “no more period poems, we’ve got that covered!” But it wasn’t just about topic. It was also about style. There’s some experimental work in HYSTERIA that I don’t know I would have read or picked up if I were shopping in a bookstore, but that I’m glad showed up in my inbox because it spoke to me within the context of this project.

And diversity of cultural background was important to me, too. And by cultural background I mean race, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation and gender identity. I really wanted pieces about wearing a hijab. About bat mitzvahs. About non-hetero sex. I hope I did a good job with this. I hope I found authors and pieces that people enjoy and relate to and learn from.

What do you think the anthology speaks to in the climate we're in right now – as women, as creatives?

You know, every day it feels like there’s something else going down that I want to throw this book at. Women being told their dreadlocks are unprofessional. Women’s tough questions being written off as the result of PMS. (Looking at you, Trump.) Bills being passed that could undo years of work for women’s rights. People trying to tell me, personally, that “hysterical” is just a colloquialism and not a gendered hate word. Folks thinking that just because we’ve achieved parity in one little bubble of the lit world that sexism is over for all of lit. The VIDA counts for big magazines (hello, the Atlantic) and smaller magazines. Songs on the radio. Things I overhear kids say to each other when I write at the Starbucks that’s next to the middle school.

So often we think, well, it’s just a joke. It’s just one guy. It’s just one magazine. It’s just a handful of nut-jobs. It’s just the radical right, and their minds can’t be changed. But! But. Sexism is so ingrained in us that even you and I do sexist things every day without thinking of it. I think I’ve referred to a woman I didn’t like as a bitch even this week.

I hope HYSTERIA gives us a place to talk about uncomfortable subjects, to start and continue conversations with ourselves, our daughters, our peers—but I also hope it’s a place to find comfort and community. Maybe the patriarchy isn’t listening. But maybe we can rally anyway.

I was particularly thrilled to write for this anthology. I am alongside some amazing writers and also emerging ones. How did you vote for pieces? Was this about making a space for all voices, new and established?

I read and selected the submissions myself. Aside from the solicitation—which I did ahead of time, before sending out the call—I just wanted to make sure we had everything covered. I didn’t care if folks were famous or brand new, just that the work was good. And I’m super fortunate that we did get some big names for the anthology. People who said yes when we reached out and asked. But I’m also super fortunate to have new voices with new things to say. Because that’s what community is about and I think that, in a way, that’s what HYSTERIA is about, too.

What are the plans for the anthology?

I’m hoping to set up a launch party here in Austin, TX when the book is ready. I think it will be a good time, and hopefully, as many contributors as possible can come and read. We’ll definitely be sending out review copies and doing our best to entice booksellers and librarians. We want this book in as many hands as possible. It’s a beautiful book if I don’t say so myself.

How will donations help?

The funds from the Indiegogo campaign are going to help us pay some of the up-front costs (like hiring our cover artist, Jodie Wynne, and the Adobe Cloud account we had to open to manage the many, many contracts for the individual authors) as well as printing. But the biggest reason we wanted to do an Indiegogo was so that we could pay our authors better. So if you can help us out with that, that would be amazing. Should we exceed our goal, any extra funds will go toward a launch and/or future anthology projects at Lucky Bastard Press.

Tell us what it's like to work with Lucky Bastard Press.

Lucky Bastard was founded by Allie Marini and Brennan DeFrisco and somehow I tricked them into letting me do an anthology with them. They really gave me free reign, which was scary but also really thrilling. I’m now on board with LB as a full editor, but at the time it was just, here, EKA, make a book. So I did. And I’m really excited that it’s with a press that is all about the underdogs and the long-shots. Isn’t that how many of us feel, as artists, especially as women? Lucky Bastard is here to champion the weirdos. And, in this case, it’s the hysterical weirdos that we want to show the world.

The writer list, as provided by

Lucky Bastard Press:

E. Kristin Anderson

Gayle Brandeis

Allison Joseph

Christine Heppermann

Lynn Melnick

Lizi Giliad

Lisa Marie Basile

Kia Groom

Laura Cronk

Alison Townsend

Amy King

Kirsten Smith

Aricka Foreman

Dena Rash Guzman

Kate Litterer

Paula Mendoza

Sara Cooper

Kirsten Irving

Erika T. Wurth

Natasha Trethewey

Kelli Russel Agodon

Kenzie Allen

Rita Dove

Francesca Lia Block

Patricia Smith

Lesléa Newman

Erin Elizabeth Smith

Tatiana Ryckman

Janna Layton

Mary McMyne

Sarah Lilius

Jennifer MacBain-Stephens

Elizabeth Onusko

Katie Manning

Sandra Marchetti

Sarah Ghoshal

Ivy Alvarez

Heather Kirn Lanier

Jane Eaton Hamilton

Jessica Morey-Collins

Sally Rosen Kindred

Laurie Kolp

Gabrielle Montesanti

Sonja Johanson

Meghan Privitello

Deborah Bacharach

Juliet Cook

Sarah Henning

Trish Hopkinson

Alina Borger

Christine Stoddard

Hope Wabuke

Nicole Rollende

Roxanna Bennett

MK Chavez

Catherine Moore

Jesseca Cornelson

Karen Paul Holmes

Lisa Mangini

Shevaun Brannigan

Martha Silano

Jen Karetnick

Emily Rose Cole

Sarah Kobrinsky

Addy McCulloch

Mary Lou Buschi

Sarah Frances Moran

Ellen Kombiyil

Shanna Alden

Julie "Jules" Jacob

Ariana D. Den Bleyker

Sheila Squillante

Jeannine Hall Gailey

Randon Billings Noble

Mary-Alice Daniel

Sarah J. Sloat

Minal Hajratwala

Shikha Malaviya

Elizabeth Harlan-Ferlo

Leila Chatti

Sarah B. Boyle

Jennifer K. Sweene

Nicole Tong

MANDEM

E.D. Conrads

Samantha Duncan

Susan Rich

Kristen Havens

Judith Ortiz Cofer

Hila Ratzabi

Joanna Hoffman

Elizabeth Hoover

Letitia Trent

Camille-Yvette Welsch

Erin Dorney

Shannon Elizabeth Hardwick

Anna Leahy

Majda Gama

Erin Lorandos

Amy Katherine Cannon

Nicci Mechler & Hilda Weaver

Mary Stone

Jessica Rae Bergamino

Jennifer Givhan

Hilary King

Sara Adams

Bri Blue

Vicki Iorio

Natasha Marin

Tanya Muzumdar

Miranda Tsang

Jessica L. Walsh

Lucia Cherciu

Melissa Hassard

Nora Hickey

Dorothea Lasky

Siaara Freeman

Deborah Hauser

Suzanne Langlois

Eman Hassan

Amber Flame

Lisa Eve Cheby

Soniah Kamal

M. Mack

Teresa Dzieglewicz

Geula Geurts

Jennifer Martelli

Carleen Tibbetts

Katelyn L. Radtke

Cleveland Wall

Stacey Balkun

Autism Isn't a Dirty Word, But It Feels Like One

I’m sitting at my computer desk when the email appears in my inbox.

“We’re honored to invite you...” It’s my undergraduate university, asking me to appear as an alumni speaker at the annual Spring Gathering.

I already know what my friends will say when I tell them about it. “Wow, but you’re only a year out of school!” “I told you, you’re the most successful person in our class!”

I stare at the email, blinking several times just to see if it will disappear.

Read More7 Books You'll Actually Enjoy Reading

These are books I've read in the last few months. I loved them, so I want you to love them too.

Read MoreThe Night We Didn’t Fall In Love

A female body in mom jeans looks at a water color of Bianca Stone’s depicting the three fates. Only one faces us and says in her speech bubble, “I’m filled with rooms I’ve never seen before.” It hangs in my living room. I am the female body, a room I see so much of I don’t see it at all. I see it so little that I’m usually digging my nails into my skin in order to get anything practical done without overwhelming anxiety. How do I get this out of the room? I got Netflix binge-streaming House of Cards to distract me from my loneliness and this. I miss something I’ve never had, stupid saudade. How much of the wine bottle has been drunk and will it get me to the end of the night?

Read MoreArt as a Blend of Many Truths: Why We Shouldn't Question Beyoncé's Narrative

To tell a story (even your own), in a way, is to tell someone else’s–if it were only hers, how could we connect? How could we expect her to own every word? Why must it be debunked or defined at all?

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

Lemonade emerged from darkness at a time of political unrest and volatile racism. For many, I’m sure, it also comes about as a Spring story of rebirth and the divine self; Lemonade’s grief is collective and personal–the story she weaves is everyone’s story, an eternal hurt, the story of mothers who broke at the hands of men, the story of a girl who was too naive, the story of women who take back their agency.

Everyone keeps worrying about the truth; what’s the truth? Is the artist being cheated on? Did she forgive him? Why is he seen, on camera, stroking her ankles, kissing her face? What if it’s about her own mother? What if this is a machine? What if the artist is exploiting rumors about her marriage–and feeding the beast that way? What if the beast isn’t her own?

The fact is that the artist doesn’t always need to have experienced everything first-hand. Certainly, Beyoncé is building a world, one that is universally understood enough to be appreciated: the grief of lost love, the grief of being lied-to, the relentless anger, the baptismal, personal resurrection, the lover's possible forgiveness, the healing power of culture.

One of the ways she builds this world is by featuring the words of poet Warsan Shire. In a New Yorker piece that pre-dated Lemonade by several months, it is clear that even Shire doesn’t claim her work is entirely autobiographical:

“How much of the book is autobiographical is never really made clear, but beside the point. (Though Shire has said, “I either know, or I am every person I have written about, for or as. But I do imagine them in their most intimate settings.”) It’s East African storytelling and coming-of-age memoir fused into one. It’s a first-generation woman always looking backward and forward at the same time, acknowledging that to move through life without being haunted by the past lives of your forebears is impossible.”

This is how art works. As a poet, I play a character and the character plays me–always vacillating between this point in time and that point in time and heart, time owned by me or time owned by someone else, heart owned by me, and heart owned by other. It’s the million ghosts that tell the story, and they’re needed to give it dimension.

We should give artists–and I’m calling Beyoncé an artist, here, and if you don’t like that, bye–the ability to make their art into something alchemical; a little this, a little that. It’s the potion of the collective unconscious, that which is passed down by ancestors, mixed with our consciousness and our memories, our collective experiences of love and sorrow. To tell a story (even your own), in a way, is to tell someone else’s–and if it were only hers, how could we connect? How could we expect her to own every word? Why must it be debunked or defined at all? Why isn't it ok to tell the story of something bigger?

In Lemonade, Beyoncé handles the past–through her grandmother’s voice, Shire’s voice, the history of race in America, the way love has treated her–the present, and the future: a future of hope, a heaven that is a “love without betrayal,” the dissolution of racism, the reclaiming of feminine power, nature as a symbol of forward momentum.

I think we are begging for these many voices, these many moving parts she has woven; I am happy it was a collaboration. It gives me hope for art.

And don’t drink the Haterade: “It’s her producers, it’s the songwriters, it’s the people she hired.” When people reduce any artist to this, they’re reducing art, which I suspect is antithetical to their whole point. Being an artist takes knowing how to harness the power of many, it takes knowing how to build a vision, and it takes knowing how to embody that world. Nothing can be done alone.

The time you spend questioning her writing credits, her veracity, her money – is time you could be devoting to the very moving art created by Beyoncé and her team – poets and directors and the powerful Black women she features. It says something, and if you give it the space, I’m sure it will talk to you.

Lisa Marie Basile is a NYC-based poet, editor, and writer. She’s the founding editor-in-chief of Luna Luna Magazine, and her work has appeared in The Establishment, Bustle, Hello Giggles, The Gloss, xoJane, Good Housekeeping, Redbook, and The Huffington Post, among other sites. She is the author of Apocryphal (Noctuary Press, Uni of Buffalo) and a few chapbooks. Her work as a poet and editor have been featured in Amy Poehler’s Smart Girls, The New York Daily News, Best American Poetry, and The Rumpus, and PANK, among others. She currently works for Hearst Digital Media, where she edits for The Mix, their contributor network. Follow her on Twitter@lisamariebasile.

Finding an Unlikely Home in NYC

The small courtyard is crowded with splintered cafeteria tables cluttered with various items in various states of cleanliness: worn black Reeboks, outgrown children’s clothes, hoards of garish costume jewelry, books that should have been long ago returned to a library, disc-man headphones with slightly gnawed on connection jacks, and, the most archaeological finding of all, teetering pillars of VHS’s stacked haphazardly atop each other like ruins. There does not appear to be any connection amongst the miscellaneous items shoved onto a table save for the fact that they all belong to the flea market vendor’s past. All together they tell the story of a life; a story that is for sale; memories for a dollar fifty. The Immaculate Conception courtyard, home to the flea market on weekends, cramped with used objects and worn people, is hemmed in by buildings of prestige on either side of it.

Read MoreReview of Atoosa Grey's 'Black Hollyhock'

Black Hollyhock, Atoosa Grey’s first poetry collection, faithfully adheres to its title. While voluptuously organic, it also contains a dolorous underside. Grey’s image-driven poems, imbued with symbolism, navigate territories within territories -- those of language, identity, motherhood and the body. She deftly renders a world nuanced with languid musicality and replete with questions. She asks us to consider the currency of words, to find the sublime in the mundane, and to recognize the inevitability of rebirth and resurrection throughout our lives: “The body has its own way of dying / again / and again.”

Read MoreInterview with Roberto Montes on 'I Don’t Know Do You'

Roberto Montes’ "I Don’t Know Do You" was named one of the Best Books of 2014 by NPR and was also a finalist for the Thom Gunn Award for Gay Poetry from the Publishing Triangle. This says a lot for a first book. But there is so much more here. Montes’ poems speak eloquently on the trials and travails of living in our modern society, of growth and change, of politics and poetics, and mostly of love in its many forms and formats. I consider myself lucky to call Roberto a friend and colleague. We graduated together in 2013 from the New School’s MFA program. Lucky ‘13 – I like to call it. Our graduating class of twenty-seven poets has already made great inroads, at least seven of us have books out or forthcoming; and we’re all forging forward in our own ways while learning how to navigate the strange and exciting world of Poetry and Publishing.

Read MoreThe Trials of Writing Haibun About the Salem Witch Trials

Hands down, the best decision of my life was joining a low-residency MFA in Creative Writing program. When I think about my experience, I imagine Mike Teavee from Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. My poems, like Mike, started out normal sized and a bit naive. Then they shrunk. This tiny poem phase didn’t so much reflect the length of the verse, but instead the humbling of my ego. Everywhere I went, I met beautiful poets and read amazing collections. I currently take in every bit I can of anything that might even closely resemble a poem so that my tiny, metaphysical mind-poem can grow. And that’s just what it’s doing.

Read More