Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, Sexting Ghosts, Xenos, No(body), #Survivor: A Photo Series (forthcoming), and A Love Story (Vegetarian Alcoholic Press, 2021). They are the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault and the illustrator of Dead Tongue (Yes Poetry, 2020). They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College, and Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine.

Read MoreDolls and Meadows: An Interview with Poet Kristin Garth

BY MONIQUE QUINTANA, IN INTERVIEW WITH KRISTIN GARTH

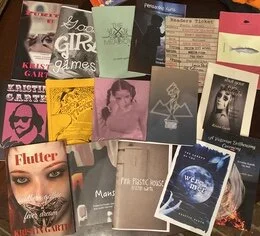

Poet and editor Kristin Garth has created a career that plays with technology, new school pastels, and old Hollywood glamour. All of her literary endeavors are empathetically experimental, provocative, and nurture sex-positivity. I reviewed Garth's chapbook, Shut Your Eyes, Succubi last winter, and wanted to inquire more about her lyrical inclinations and what's coming for her next.

Kristin Garth

Monique Quintana: I love how you advocate for sex-positivity in literature. What was your journey towards sex positivity, and how is that reflected in the Pink Plastic House's architecture?

Kristin Garth: Thank you so much for this compliment. Sex positivity and sexual honesty are two qualities I find essential in a healthy psychology. I came from an abusive, extremely religious home, a home where people feared the body and sexuality — but also were obsessed with these things. As a young girl, I developed physically early, and I was also sexually abused early in my life.

In this way, sexuality has been a part of my life as long as I can remember. It wasn't a choice to learn about it, but you can't unknow it.

I have spoken to many other survivors of childhood sexual assault over the years in group therapy settings and just through friendships. I know for many survivors, sexuality becomes, post the trauma of childhood sexual abuse, a dark and intolerable, of barely tolerable, event.

Others, including me, comfort themselves with sexuality or attempt to — I certainly did. I would lock myself in the bathroom in elementary school, and touch myself, feel a sense of triumph and autonomy in these moments that my body was still mine. Fantasized about a future where I wouldn't have to hide or lie — where I wouldn't rage with my sex like my abuser. I would just be who I was and speak what I needed.

Pink Plastic House a tiny journal, represents this kind of complex, whole person I wanted to be. A house, when I was young, felt simply unsafe. It was people by adults who took what they wanted and deprived you of privacy/dignity and expected you to present a lie of purity to the world — a "purity" of which they deprived you.

The Pink Plastic House is safe and also complex in the way that honest worlds are — they have basements where people's darker urges manifest in consensual, communicative ways with adults. They have tea parties and slumber parties, too, because the Pink Plastic House's architecture is designed by a womanchild who is kinky and innocent, adult and emotionally still a little stunted and forever a child in the way that some survivors of sexual abuse are.

I place poems in Pink Plastic House a tiny journal into the rooms I feel they belong. It grows all the time with new elements emerging just like the honest and open human soul does. It's also developed a neighborhood of associated journals that deal with erotica and kink (Poke) and horror (The Haunted Dollhouse). These two journals both emerged out of a lack, I felt, of space for horror and sex writing in the post-pandemic world. Many journals began restricting their submissions to prohibit these categories.

I felt an urgent need to keep the lit world complex and give people like me a chance to voice their kink and horror because I know that doing that brings me peace. To feel restricted in my voice, I feel like I'm back with the Puritans again. I never want anyone to feel like that.

It t's ironic that Pink Plastic House a tiny journal came from the title of my first chapbook Pink Plastic House. The title poem of that chapbook is about me as a stripper playing with and populating a Barbie dreamhouse after work.

I stripped in pigtails and braids and schoolgirl uniforms for five years to establish my financial autonomy from my abusers. At that time, I think the house represented my loneliness and the normalcy that I craved so much. Writing about that lonely Barbie house and creating a journal in its name has connected me to countless people decades after that lonely schoolgirl stripper took off her clothes to be free. The Pink Plastic House represents community and wholeness to me now, and that's the power of writing — how it can transform your life.

MQ: Not only are you prolific in your writing ventures, but you have edited numerous projects. Anthologies are especially challenging to put together. What are a few pieces of advice you could give writers who want to pursue publishing an anthology?

KG: I have edited four anthologies, three with a partner and one alone. Justin Karcher was my first editorial partner. We worked together on Mansion, a Slenderman anthology, and These Poems Are Not What They Seem, a Twin Peaks anthology (in which you had a fantastic poem!). I had the idea for Mansion and shared it with Justin long before I had the Pink Plastic House journal or any editorial experience. He said we should do this and I felt empowered because he had the editorial experience I lacked.

I definitely think that is a great way to gain editorial experience is to work with a more experienced editor. If you have an idea for an anthology and feel lacking in the skills to execute, find yourself a more experienced partner. I'm a very hard-working human, and I love learning. I just needed someone who knew more than me about tech and editing.

Even on my newest anthology that it is my first solo project and the first publication of Pink Plastic Press, Pinkprint (the first of many. I hope, anthologies of work from Pink Plastic House journals), I hired Jeremy Gaulke of APEP, who has published me (and published the Twin Peaks anthology) before to print and design a cover. It was another way to ask for and receive a second pair of experienced eyes on this manuscript. Collaboration with people who know more than you is always good, I feel.

MQ: You often use video to share and promote your work on Instagram and Twitter. What do you specifically appreciate about each platform? If a writer could only use one of those platforms, which would you recommend and why?

KG: Wow. This is such a hard question, which is ironic because, for years, I said I'd never join Instagram. It was a statement completely informed by my ignorance of the platform.

People were always telling me I was a natural to be on Instagram because I make so many videos and post my selfies and socks.

I have been in the Twitter literary scene since 2017, and I am beyond grateful to Twitter to give me the space to finally be myself. I write a lot and publish a lot, and it was marvelous to have a place to share that.

I'm an introvert, stay-at-home girl in a small southern town. I don't have a local poetry scene I'm affiliated with — Twitter became that. By doing the videos, I felt like I was reading for my friends and people got to experience that as if we are in the same hometown.

It's sort of amazing that I'm known for my poetry readings being a poet who has never read in public "in real life." I had an engagement to teach a Delta State workshop at the Southern Literary Festival that was cancelled by the pandemic. After the pandemic, I began to feel that maybe I'd only be an online poetry reader, and maybe that's okay.

Poetry Twitter gave me a voice, and I spent so much time there that I did not believe I had time for another platform. To be honest, the only reason I joined Instagram is that in the middle of doing editing on The Meadow, a very vulnerable book I wrote about my experiences in BDSM as a young woman, my publisher at APEP left Twitter to focus on one social media platform. Since we communicated a lot during the writing of this book, a lot in messages, he told me I could talk to him there. So I got myself together and did what people had encouraged me to do — have an Instagram to archive my socks and sonnets and videos.

Twitter is very fulfilling to me for the friendships I've made and the opportunities present in the literary community. All my books came to pass through Twitter conversations and my would-be speaking engagement. I have a weekly sonnet podcast with Gadget G Radio called Kristin Whispers Sonnets that I was invited to do because of Twitter. Though I have come to love Instagram better in its actual layout and the archiving of video, for example, I could never betray Twitter, which has given me so much.

Though Pink Plastic House has a vacation Instagram house that has become a much a part of the journal as my website, so if you asked the house, she might have a different answer.

MQ: I love the film aesthetics of Anna Biller, Dario Argento, and Alejandro Jodorowsky and literary aesthetics as different as Edgar Allan Poe and Marguerite Duras and Guillermo Gomez-Peña. Your aesthetic is literary and cinematic. What are some artistic aesthetics that resonate with you that people would be surprised to hear? Whose aesthetic dollhouse would you like to spend a day?

KG: Thank you so much for calling my poetry cinematic. That means a lot as I primarily write Shakespearean sonnets, and it's always been important to me to try to create a world in 14 lines. I love films and how they engage all your senses and transport you places.

Obviously, I am a huge David Lynch fan, with my favorites by him being Mulholland Drive and the Twin Peaks film and series. That really wouldn't surprise many, though, as I've written many poems about Twin Peaks, and I've published the anthology about it.

I am so influenced by many other filmmakers, though from Whit Stillman, whose movies like Metropolitan taught me about dialogue and it's importance to the bravery of a filmmaker like Catherine Hardwicke in making the film Thirteen with its honest portrayals of troubled adolescence — to which I very much relate.

It's hard to speak about the raw truths of an abused child in a public way. I feel such a debt to films I watched, and books like We Were The Mulvaneys and Beasts by Joyce Carol Oates, as an example, that deal with sexual trauma, societal dynamics, and power imbalances. Reading books like these made it feel doable in an engaging, artistic way and my voice worthy of being heard.

I would love to be invited into anyone's dollhouse. I have three myself — an old wooden one that has been through a lot and became the logo of the literary journal. I also have a Barbie dreamhouse and a Disney Cinderella castle replica. I have an ongoing feature of poets who have dollhouses that has featured Kolleen Carney and Kailey Tedesco so far. I feel like it's my chance to virtually commune with other poet dollhouse lovers. That's a subset of people I just adore, so if you are one of them, feel free to reach out because I'd love to know you and for you to be in The Real Dollhouse Poets of The Pink Plastic Plasticity.

MQ: In your APEP Publications chapbook, The Meadow, the speaker takes a journey through hurt while at the same time recognizing intricate beauty and the body politics of BDSM. The speaker has autonomy through a memoir. What is a future "meadow" you envision walking down?

KG: That's such a lovely description of The Meadow, thank you. The Meadow is a book I've been wanting to write for twenty years. In fact, there is a poem inside of it called "Homecoming," which was my first and only publication until I was 43 and became who I was supposed to be.

The story of the publication of the sonnet "Homecoming" in No Other Tribute: Erotic Tales of Women in Submission, edited by Laura Antoniou, tells a lot about me at this time of my life. I wrote this sonnet and gave it to my first dom when I was just discovering the BDSM scene in my early 20's. I received a partial scholarship to graduate school in creative writing because of my sonnets, many of which were sexual and kinky as characterize many of my sonnets, but I would end up dropping out of graduate school to strip to have the financial autonomy to live my life away from abuse.

Even though I was in school studying writing, I didn't submit my poetry anywhere. Didn't have the strength yet to even contemplate that kind of rejection after the tortures of my childhood. I submitted, though sexually, and I gave this poem to my much older dom, who was also a writer. He didn't tell me, but he submitted it to Laura Antoniou's anthology, where it was accepted. At that point, of course, he told me to gain my consent to move forward with the publication, and I was shocked but delighted.

It was published under my scene name as pseudonym (Scarlet), and it was the only poem accepted in a collection of prose. The editor wrote the kindest introduction about me, how she couldn't help but publish this poem. It was that magical kind of publication experience that can change your life.

Of course, for me, it would take almost twenty years before I worked up the courage to submit myself in writing. But I always knew I eventually would because of the way this experience had made me feel seen in a world in which I was still invisible.

I had published it under a pseudonym, which made me very sad at the time because I feared my parents would find out. I still lived at home. I hated not being able to own my experiences due to abuse and the threat of more. I swore one day I would write whatever I felt with my name and be known for that name. Almost 700 publications later, I know my younger self would be so proud of the Kristin Garth I have become.

I am my meadow now. I feel I had to undergo the catharsis of hurt to discover myself — and sometimes I find myself in its thorns again. But I also ache for the petals and the dew of the meadow. I am learning to nourish and cultivate myself better and make roots, and value rest and replenishment. I don't leave myself open to predators and the elements the way I did in the desperation of my wandering youth. There is an architect in the meadow now. I am building a cottage. I am learning to shelter.

Kristin Garth is a Pushcart, Best of the Net & Rhysling nominated sonnet stalker. Her sonnets have stalked journals like Glass, Yes, Five:2: One, Luna Luna, and more. She is the author of seventeen books of poetry including Pink Plastic House (Maverick Duck Press), Crow Carriage (The Hedgehog Poetry Press), Flutter: Southern Gothic Fever Dream (TwistiT Press), The Meadow (APEP Publications), and Golden Ticket from Roaring Junior Press. She is the founder of Pink Plastic House a tiny journal and co-founder of Performance Anxiety, an online poetry reading series. Follow her on Twitter and her website.

Monique Quintana is a Xicana from Fresno, CA, and the author of the novella Cenote City (Clash Books, 2019). Her short works have been nominated for Best of the Net, Best Microfiction, and the Pushcart Prize. She has also been awarded artist residencies to Yaddo, The Mineral School, and Sundress Academy of the Arts. She has also received fellowships to the Community of Writers, the Open Mouth Poetry Retreat, and she was the inaugural winner of Amplify’s Megaphone Fellowship for a Writer of Color. You can find her @quintanagothic and moniquequintana.com.

A Playlist for The Empress

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, Sexting Ghosts, Xenos, No(body), #Survivor: A Photo Series (forthcoming), and A Love Story (Vegetarian Alcoholic Press, 2021). They are the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault and the illustrator of Dead Tongue (Yes Poetry, 2020). They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College, and Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine.

Read MorePhoto by Brighton Galvan

An Interview with 'Bareback Nightfall' Author Joshua Escobar

…like learning how to drink water after the world has turned upside-down…

Read MorePhoto courtesy of Lucé Tomlin-Brenner

Lucé Tomlin-Brenner Talks Witchcraft, Practical Magic & Staying Spooky All Year

So, if you find yourself asking questions such as, where did Halloween come from? How did it get to America? Why do we do the things we do—bob for apples, pull pranks, go to haunted houses, etc.—to celebrate this strange, shadowy time of year?

Then It’s Always Halloween is just for you.

Read MoreA Playlist for The High Priestess

BY JOANNA C. VALENTE

Because I love playlists and Tarot, I decided to merge the two. For each Major Arcana card, I’m making a playlist. Here is the one for The High Priestess. In a similar vein, I had made playlists for each zodiac sign, which you can check out here. All Tarot playlists can be found here.

From Lucidvox to The Cure, this playlist aspires to let you dig into your intuition and spiritual self. Link here and below.

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, Sexting Ghosts, Xenos, No(body), #Survivor: A Photo Series (forthcoming), and A Love Story (Vegetarian Alcoholic Press, 2021). They are the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault and the illustrator of Dead Tongue (Yes Poetry, 2020). They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College, and Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine.

Photos by LISA MARIE BASILE

A holy little thing: writing and ancestral magic

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

Editor’s Note: This was first published in Ritual Poetica

LISA MARIE BASILE

My grandmother — or nonna — was born Concetta Maria Lipari. She went by the name Mary, at least in the United States. She emigrated with her sisters, by sea, from Palermo, Sicily.

“I saw Mussolini’s men under the lemon trees,” she told me once when I was in my mid-twenties. It would be one of the last times I saw her, her wrinkled hands held in my father’s palms. I was too young, too distracted, and too naive, to ask her for more memories.

The idea of her living under that regime becomes more real to me as I grow older, wiser, and more interested in how identities and places change due to oppression and ideology. How Sicily was ruled and conquered more than anywhere else, how all that change, fear, culture, and belief exists in my blood today. How it shows up in America, too. The salt and all the tides of time. And how we reckon with it.

I also think of the lemons. Those beautiful bright gifts from heaven; how, years after her death, I’d step foot onto Italian soil to taste their sweetness, to wander limoncello-drunk down Duomo steps and through piazzas and little streets. I started in the North on Lago Maggiore and made my way down through Naples to the Amalfi Coast. I still haven’t tasted Palermo, drank of my own blood.

There is magic in nature. In salt and lemon and water. And I think my grandmother knew this, although she wouldn’t refer to it as such. She was a devout Catholic — she’d go to church every day, maybe twice per day. She and my grandfather attended the Saint Gianna Beretta Molla Parish down in South Jersey, and when I attended both of their funerals, with the same funereal rites — the songs and smoke and procession — I felt that same intoxication I did as a child. I was again reminded of the power of ritual. The institution and its rites are overwhelming, luminous, frightening, and not a bit complicated. That tendency toward ritual, toward the magic and mysticism of action and intent, is etched into me. The primordial Paganism that was rewritten with fear and shadow — and yet I found some comfort in it.

I recall my grandmother doing a few things that bewildered me as a younger person. First, she pulled out a box of her own long, thick black hair — darker than my own — and waved it over our cake as we sat eating. My aunt promptly said, “Mom — we can put that away?!” But it was something about preserving her youth, reclaiming her power, keeping memories, staying safe. It was, I suppose, a spell of sorts. She lived well into her 90s.

LISA MARIE BASILE

My other memories are of altars and shrines — over the television, on shelves, in corners covered in embroidered cloth, candles, sacred images, tiny statuettes (one of which I took for myself, or was given; I can’t remember), crucifixion triptychs, figurines, vials, relics, holy water collected in old Cola bottles, taped with pictures of Jesus or the saints. I can almost evoke the scent of their home. Perfume, something dry and old, incense, the smell of the air in South Jersey—a specific mix of something and trees. It has all become mythology to me.

And upon the altars were scrolls — dozens of tiny scrolls, etched with prayers and blessings, wishes, and words in both Sicilian and in English. She’d slip the scrolls in between statues of saints and figurines, roll them up under hanging rosaries. Once, when I knew it was the end, I stole two of the papers. I felt she would forgive me. I wanted something of hers, something handwritten. Something beautiful. As a writer, it felt only right. Or perhaps that’s me romanticizing everything.

My grandmother wasn’t a warm woman. She had seven children and dozens of grandchildren — and she brutally picked favorites. The fear of God led her to judgment and cruelty in many ways, and we were not close for many reasons. As a child, she didn’t hold me in her lap or stroke my hair or care for me. She visited, we made dishes and dishes of food, she told me I was too skinny, and she sent me scapulars and bottles of holy water. She also warned me about the Devil and told me ghost stories. They were violent and strange and they haunt me today — the man who killed himself in her basement. The child swinging on a chandelier. The old woman dressed in black who came in and out of the house.

These stories were always told or spoken about at family dinners. The consensus was that Grandma Mary had ‘lost her marbles,’ or always been a bit off, that perhaps having seven children had worn her down. Perhaps it was emigration and a loss of her culture, assimilation, her marriage, the wars, or mental health issues. I think it is a mix.

LISA MARIE BASILE

But I am not so sure it wasn’t something else, too. Something divine or ghastly. I don’t know what I think of the afterlife, but I know my grandmother was tuned in to something. Some otherness. Some else-ness. She seemed to have existed in a magical realist realm. It seemed only loosely tethered to here and now. Of course, only in retrospect can you see these truths for what they are.

My mother, who isn’t Sicilian, always says, “You’re just like your grandmother Mary.” I can’t tell if it’s a good thing, but it’s a potent thing. I do have her pale olive skin, her dark hair. We are both water signs.

In this way, intuiting the power of the word was passed down to me. I now use scrolls on my own altars. I have been doing it before I knew I was doing it — before I thought of myself as a word witch or an alchemist of letters or a poet, and before I believed in anything at all.

I have always kept journals and wrote letters and I would throw wishes into rivers at a child. The writing felt Important to me. Performing poems aloud felt like I was achieving something, casting something out. Exorcising, incanting, making, even if I didn’t have the words for it nor the conscious cognisance of intention and belief.

I think of my grandmother’s use of scrolls as a Benedicaria, a (purposefully?) vague and recent term for Southern Italian or Sicilian traditions of blessings. Benedicaria is at its core Catholic, yet it operates without explicit language, without much ado. In Campania, where I traveled alone last year, it’s translated into do a little holy thing (Fa Lu Santuccio).

In my limited understanding, it is an innate, religious understanding of things you just do — in your house or with your family or in your kitchen. It’s intuited, not fancy, and detached from glossaries and definitions. It’s not stregheria, either. It’s something different.

It’s sacramentals and olive oil and warding off the evil eye. Saving hair and writing scrolls. It isn’t magical, and she wouldn’t want to see it that way. It’s just what you do.

Ironically, given this entire post and its emphasis on the Word, what my grandmother was doing — and what I do — doesn’t have a specific name. I may call it magic or witchcraft, and she may have called it prayer (especially writing in her mother tongue, which was, in many ways, taken from her). But it’s just what feels natural.

Writing is part of who I am. It is my sacredness and my profanity. My prayer and my craft. My impact, my wound, and my reclamation. A product of a divinity or a call to it. An ancestral power that I’ve tapped into, but one that feels, somewhat, on loan to me. I am a recipient of a message. I am a vessel. Maybe it comes from a God, or a saint. Maybe it comes from history’s echoes, some sort of ancestral hum. Maybe it’s a gene. Maybe it is a gift. Or maybe not at all.

I will fill my own life, and this world, with a sea of letters, stained by lemon and sunlight, and hope that it washes something beautiful to shore. It’s just a holy little thing, writing. It creates something from nothing. It’s my meaning. It is my thank you to existence.

Lisa Marie Basile is the founding creative director of Luna Luna Magazine, & the author of a few books of poetry and nonfiction, including Light Magic for Dark Times and The Magical Writing Grimoire. She's written for or been featured in The New York Times, Entropy, Grimoire Magazine, Sabat Magazine, Giallo Lit, Catapult, The Atlas Review, Best American Experimental Writing, and more.

Electroluminescence, a poem

BY RENA MEDOW

Electroluminescence

Last night I felt like watching a thriller

taking in someone else’s damages for once.

I collect all your pale thank you’s

more transparent than a moon.

I prefer to think of others’ lives

lived in a series of miniature rooms

in a grand solar in some far away museum.

I am growing so tired of mine. I fall asleep alone and wake up alone,

but always another rustles around in the middle hours.

Their phone light not a lighthouse, no electroluminescent beacon home—

The trees without leaves service only northbound crows.

This is how it always ends, a love stripped bare and planted in

cold soil.

My mouth sings a song of itself, for itself, dying at its own pace.

I pull corpses from their roots and toss them to the curb.

Across the road, donkeys graze the pasture. In the road,

two yellow lines parallel extend towards nowhere, which

is near here, I hear. The tree I’m beneath is the descendant of trees.

That donkey there, the descendant of donkeys.

I forage for kindling with bugs in my hair,

a gymnasium of wet curls. It takes two matches to light the fire, six

in the rain. An illusion of self-sufficiency. Here, I only save

caterpillars from barn cats, not love from

thrown objects and raised voices.

No, even when I enter the orchard

to pick windfalls off the ground, and strain my worn

body, there are four bushels at the end.

Three to give back, one to take home. If only the heart could get a quarter

of what it gives, to munch on later. Worm and all.

The trumpet of day flat-tones against the trees,

and I savor this bland life, forever a matter of too much or too little.

Rena Medow attended the New School for poetry, Emily Carr University for painting and the Langara Certificate program for Journalism. Her first poetry chapbook, "I Have been Packing This Suitcase All My Life So Why Is It Empty?" came out in the fall of 2017 from Vegetarian Alcoholic Press. Her poems, essays, articles and illustrations have been featured in a variety of places, including The Vancouver Sun, Langara Voice, VICE, LunaLuna Magazine and The Minetta Review.

First Comes the Egg

Burning just the tip of a newspaper in an ear to relieve pain. Burying tiny sculptures of santos in the front yard to ward off evil spirits. Limpias from a shaman when hope is finite. I no longer live where I grew up—there’s no neighborhood curandera to visit me.

Read MoreBy Adrian Ernesto Cepeda

Sylvia Plath: Madre from Beyond

BY ADRIAN ERNESTO CEPEDA

“I need a mother. I need some older, wiser being to cry to. I talk to God, but the sky is empty.”

― Sylvia Plath

I know many are going to ask how did I get here? Emotionally, physically sick with mental health issues. Some may ask how can you have depression when you have published three acclaimed poetry collections? My life changed on November 11, 2017. Mi Mami died, four months before my first poetry collection Flashes and Verses…Becoming Attractions was published in March 2018 by Unsolicited Press. My mother was my number one supporter of mi poesia, and my drive to be published. When no one else did, she believed and saw the potential of my life’s calling, mi Mami was the one who gave me the gift of la poesía. She has always been my number one champion. When I was working as a retail servant, at every bookstore and record shop, you could imagine, she believed that I was more than a bookseller and I had poetry that needed to expressed, written and shared with the world. I would send her poemas for her cumpleaños and navidad. She called them gifts from my Corazon. Mami was more than my motivational compass, it was her belief in my calling to become a published poeta that focused every volume of my creative light. `

After she passed away, I realize now that I was in denial, for three years. Her death overshadowed all my publication successes. Since 2017, I spent this time promoting my three poetry books, especially my latest La Belle Ajar, a collection of cento poems inspired by Sylvia Plath’s 1963 novel and focusing on my career as a published poet. Instead of facing all the complex emotions of mourning the death of mi Mami, I compartmentalized these feelings, I was not ready to face, and worked on trying to make a name for myself in the publishing world. Foolishly I actually believed that publishing these books would somehow lessen the pain and make me happy. The opposite happened. With every book, positive review and acclaim from my community of poets and writers, something was missing. There was this huge gap of grief in my life that I was trying to fill with my success as a published poet.

So, I went looking for mother figures to try to replace the hole that was left after mi Mami died. But that just caused even more pain and confusion. While I was trying to help mi familia settle mi Mami’s estate, I became sick from not facing any of the issues of my mother’s death. This is when I rediscovered Sylvia Plath. For over a year she became my surrogate Mother. I turned to her words, her poems, her stories, her diaries, her quotes for guidance and for a while, her supernatural support helped me. Then one day, whilst I was reading one of the many biographies, from the plethora of books I bought to learn from mi Madre from beyond, towards the end of this bio I came to the part where Plath dies. And even though in my conscious mind I knew that Plath had taken her life on February 11, 1963, the part of me that was needing a mother figure was devastated. It felt like I had lost another madre and this was the beginning of where my story starts to turn towards my health crisis.

I should’ve known when I was reading Sylvia’s poem, “The Morning Song” when she wrote:

I’m no more your mother

Than the cloud that distills a mirror to reflect its own slow

Effacement at the wind’s hand.

It was obvious. It felt like Plath was speaking to me, especially at the end of the poem:

Whitens and swallows its dull stars. And now you try

Your handful of notes;

The clear vowels rise like balloons.

Towards the end of the summer of the pandemic, the balloon that held the grief for the death of mi Mami popped. Just like Sylvia Plath once wrote: “See, the darkness is leaking from the cracks. I cannot contain it. I cannot contain my life.” Since 2017, I had avoided facing any of the sorrow of her passing and it manifested in ailments, illnesses and sickness that would take over my body. Horrible acid reflux, hay fever, whopping cough, recurring influenzas, crippling back, leg and muscle spasms along with outbreaks of shingles was my body telling me I was hurting emotionally from the inside. It was the loss of mi Mami that I did not want to face. All of this pain was manifesting in all of these symptoms. I was missing her and was afraid to admit it. For years I would call mi Mami on the telephone and if I were stressed out, worried or sick, her words, advice or just hearing my mother’s voice would make me feel better. Since she died, I had no one to connect with, I missed mi Mami and I was desperately trying to find someone or some mother figure to take her place. This is why I turned to Sylvia Plath. But after I finished my book La Belle Ajar, I realize now I was missing mi Mami more. My condition worsened during the shutdown. I was suffering from daily debilitating anxiety attacks and I know I was not the only one. Plath said it best when she wrote in her journal: “I have much to live for, yet unaccountably I am sick and sad.” I talked to and know of so many poets and writers who were dealing with recurring traumas, depression and grief during the pandemic and I was no different. It wasn’t just the emotions of her grief, there were so many reasons for my sicknesses. Sylvia Plath perfectly described my physical symptoms that I was battling on a daily basis when she described:

The sickness rolled through me in great waves. After each wave it would fade away and leave me limp as a wet leaf and shivering all over and then I would feel it rising up in me again, and the glittering white torture chamber tiles under my feet and over my head and all four sides closed in and squeezed me to pieces.

More than rock bottom, physically and emotionally every day worsened, I felt like I was in pieces. My panic attacks worsened my daily medications that I was taking for my health issues stopped working, my anxiety went out of control, I couldn’t swallow food nor eat. And worse, I had insomnia, the worst of my life. I was emotionally and physically sick. But I was in denial believing that my suffering was physical and not mental like Plath once wrote:

I wanted to tell her that if only something were wrong with my body it would be fine, I would rather have anything wrong with my body than something wrong with my head, but the idea seemed so involved and wearisome that I didn’t say anything. I only burrowed down further in the bed.

I felt the same way as Plath. It had to be a physical ailment that could be cured by a visit to my primary care physician but as the days rolled on, my condition became critical. Towards the third week of another month fighting this illness when, literally on my hands and knees weeping, I realized that I needed to ask for help for my mental illness.

It’s not an accident that I chose Plath as my surrogate madre. She was a reflection of the issues that I had kept simmering inside for years. When I finally found help, the right medication, and started talking to a therapist, the darkness was slowly starting to subside. The insomnia felt like a curse that was haunting me. The lack of sleep was affecting my creativity, my appetite and I felt lost alone in my exhausted and paranoid thoughts. It wasn’t till I rediscovered my creative light again when I reconnected with mi Mami, writing her letters, that it all started to make sense to me. The therapy, the medication and my daily correspondence with my Mami is what brought me back from the dark and insomnia that had been haunting me during the pandemic. Plath explained it best when she wrote: “I am terrified by this dark thing that sleeps in me.” That sleeps in me; All day I feel its soft, feathery turnings, its malignity.” I was afraid to face any of the emotions of mi Mami’s death. Looking back if I had written these letters during the period when I was struggling with promoting my poetry books, I may have faced some of these issues in a healthier way instead of burying them inside my subconscious.

Alas like my Lazarus lady from beyond, I felt my own rebirth as Plath wrote:

Comeback in broad day

To the same place, the same face, the same brute

Amused shout:

‘A miracle!’

That knocks me out.

There is a charge

This is how it is slowly starting to feel like. Like I am being recharged and resurrected into a new way of seeing life. And although I realize that Sylvia’s charge was electroshock therapy, my charge was more symbolic, of realizing my own inner chemical imbalance was affecting the rest of my living body.

It was no accident that I connected with Plath mi Madre from beyond. Lady Lazarus became a mirror of the pain that I was beginning to feel that I finally unleashed after three years of not being ready to experience the pain of mi Mami’s death.

For the eyeing of my scars, there is a charge

For the hearing of my heart——

It really goes.

There were scars, dark bags under my eyes and I didn’t want to look in the mirror. My heart would beat so fast because of my anxiety and it would go and thunder on causing my insomnia to keep me awake.

Finally, there was a charge. My charge was my medication, the right one that reconnected me to mi Mami and this led to a resurgence in my craft, my writing, my calling that I was put here to share my life through my canvas on the page.

And there is a charge, a very large charge

For a word or a touch […]

I am your opus,

I am your valuable,

I wish I could thank Sylvia. Although she had a very complicated relationship with the legacy of her dead father which she explored in some of her most famous poems like “Daddy,” sadly, Plath never found any closure over the death of her father and I did not want to follow in the painful legacy that she poured into her poetry. Although, we both eventually had different paths to our dead parents, I want to thank her surrogate guidance eventually led me back to mi Mami. Because of this, I would say muchas gracias for her words, poems and guidance helped me reunite with la memoria of my own Mami. For making me see that I am valuable and for helping me to reconnect with mi Mami three years after her death. My opus is the collection of poems, Speaking con su Sombra, that were written for and inspired by Mami. For years, I couldn’t face looking at this manuscript because I was afraid of dealing with the issues of grief and pain from mi Mami’s death. But Sylvia, was the surrogate Madre from beyond that I needed at the time. Plath led me to where I needed to be. Like Sylvia, I crawled back home, “beaten, defeated. But not as long as I can make [poems and prose] beauty out of sorrow,” it will be worth this long full circle journey to reconnect with my own blood and flesh, from the other side. This inner voyage with Sylvia Plath brought me home with Mi Mami. Sylvia guided me by showing me how to treasure the imperfect inspiration masterpiece that is my writing vida like the lines I wrote in the seventh poem of La Belle Ajar:

I lay in bed

My ache

would rouse me, peaceful

fingers, cheerful I came

fumbling the blur of tenderness

breathing exhausted, I stared….

My goal is to go further than the explorations I created with Plath on La Belle Ajar write on. Because I am reconnecting with mi Mami, it feels like she will be by my side as I go through the final stages of revising and editing the collection of poems, Speaking con su Sombra, that she inspired. Thanks to mi Mami’s guidance, I am rediscovering emotions in poems that I will explore on the canvas in each volume of my living breathing page.

Adrian Ernesto Cepeda is the author of the full-length poetry collection Flashes & Verses… Becoming Attractions from Unsolicited Press, and the poetry chapbook So Many Flowers, So Little Time from Red Mare Press. Between the Spine is a collection of erotic love poems published with Picture Show Press and La Belle Ajar, a collection of cento poems inspired by Sylvia Plath’s 1963 novel, to be published in 2020 by CLASH Books.

His poetry has been featured in Cultural Weekly, Frontier Poetry, Yes, Poetry, 24Hr Neon Magazine, Red Wolf Editions, poeticdiversity, The Wild Word, The Fem, Pussy Magic Press, Tiferet Journal, Rigorous, Palette Poetry, Rogue Agent Journal, Tin Lunchbox Review, Rhythm & Bones Lit, Anti-Heroin Chic, Neon Mariposa Magazine, The Yellow Chair Review and Lunch Ticket’s Special Issue: Celebrating 20 Years of Antioch University Los Angeles MFA in Creative Writing.

Adrian is an LA Poet who has a BA from the University of Texas at San Antonio and he is also a graduate of the MFA program at Antioch University in Los Angeles where he lives with his wife and their cat Woody Gold

Poetry by Noeme Grace C. Tabor-Farjani

BY NOEME GRACE C. TABOR-FARJANI

The mountain beckons

The mountain beckons so does this task at hand, the work waiting and waiting. The mountain is not far to behold but it calls, so leave my slippers and staff, and stare at the fire that turns air into tablets. I pray, please turn my breathing into ink.

I only feel the malty mint, the days gone by are back. The barefoot hours, stage the dance of trees in front of me. And I think: they are still there, the earth’s still here.

There are no memories of wind, but there is one that blows desire, wrapped in fresh silence. Almost a fulfillment of longing of some unknown home, or romance, or power. Vague as the clouds, gray and shapeless, moving into uncertain spaces, telling no stories but whispers the quiet moments.

I no more count the hours for nameless acts. It’s just air blowing cold. It’s just rain that looks like it will fall. It’s just what they call a gloomy day, perfect for a song and maybe more of the wonder of the eternal now.

In stillness, solitude, and surrender, all of earth will sing with my desire.

The road hides from a busy highway

The road hides from a busy highway. Those who look not for magic is lost. Trees lined, bowing to majestic dusty pathway. Those who look not for magic won’t see the silver and gold in the cobblestones. The disappearing grass, playing hide and seek with the skies.

This season, we made fires from branches who ask to make love with earth. Those who seek not magic won’t hear the stories of the clouds. Surrounded by the sea, the sky, the mountains. I sit by the wall and sing my songs until Faith cascades down to the stillness of sand, letting go of waves.

Those who seek no magic won’t ever be still, won’t dance...

See the sun, the sky, the sand, the sea, the breeze, the trees. Only they know our spells, the secret of our days. The roof is a bed the stars shelter many dreams.

Those who look not for magic is lost.

The requiem

I.

Steady the hand as not to drip the soup from that spoon: it has battled long enough in the wild, held a sword, a stone, an arrow, a knife. Now it is time to be a wife.

Soothe the trembling that wants to travel through your skin. To kill is not a sin.

Steady the hands that are unsure. If it wants more of a fill: here’s some meat, roasted well some seconds for some sweets? Does he really want to eat?

Steady the tremors from your hands as they run to your heart. The images of battles on your tables: Kitchen where spices scatter, the meals eaten by whiners, the cluttered desk, the empty screen. Maybe you let an enemy in?

Steady the thoughts and capture them. You do not divide to rule and win. You serve, you love, you write. You feed those with trembling hands. You clean the cluttered tables. You fold the fitted sheets. You fill the blank white sheets.

I tell him, let’s kill this. To kill is not a sin.

II.

When their visit wake you up

at 4, you barely have enough sleep.

They gear you up for a battle

that is not yours

and you try not to engage.

There you are with an armor

that drags you down,

a shield you can barely lift.

And the questions come

like a colony of red ants,

a swarm of wasps in your heart.

What do they call them?

●

The food is ready,

My feet are up on the porch bench

We are waiting for Iftar.

The past 29 nights

are dizzying movements

in the kitchen.

But my body is not tired.

The summer rains

are a miracle tied to the curse

of the season.

I watch the birds play

under the drizzle,

filtered by dusk.

I thought birds hide

for cover when it rains.

Twilight nears.

The earth seem content

with the caress of showers.

I bath myself in the breath

of the sky and trees.

A long time has passed,

Have I been missed

By these creatures of mist.

The Earth quietly blankets

herself, settling

in the bed of night.

The way I embrace a faith

foreign from mine.

Iftar is here.

Noeme Grace C. Tabor-Farjani has authored Letters from Libya, a chapbook of short memoirs about her family's escape from the Second Libyan Civil War in 2014. Her works have recently appeared in Your Dream Journal and Global Poemic and forthcoming in Fahmidan Journal and Rogue Agent. In 2018, she successfully defended her PhD dissertation in creative writing pedagogy. In between gardening and yoga, she teaches literature and humanities at the high school level in the Philippines. She is currently working on a chapbook of poems on spirituality and the body.

Photo: Ingrid M. Calderon-Collins

Poetry & Photography by Ingrid M. Calderon-Collins

demons

—Summer, is in the high winds—

grapes and graves pendulate

hopeless \ drained

swooping men into their elixir,

women / bee-stung / swollen

stolen

glances,

sanative—

venom/

what’s yesterday stays,

an onset

of what the night brings—

sit here, sloppy and free

eat

drink

unfasten

run from your shadow,

a beast of your pastselves bred to breed more of what mauls,

leave it to die.

The point of daffodils 🌼

I’m sorry

I’m sorry

I’m sorry

I yawned love in all the shades of pastel you own/

I want to paint your infinite so spread your legs,

Show the world how deep you go, you said—

There is not enough paint or sky to hold me, I sigh/

He laughs as he begins to sprout his wings

It’s all in numbers

How we end and how we begin

An angel laughs—but he sings

I’m sorry

I’m sorry

I’m sorry

Apologies are endless and unnecessary

if you’ve already learned that forgiveness can be silent

I’ve seen

You’ve seen a chiseled hand sculpt you into something/mouth gaped open

Not to speak

But to hold the plague of his snake

Skid slink into my feet

My brain/

A music box of screams

Tucked neatly where I bled

I carry traces of my poetry in the morning

as I eat

And in the dusk when I’m asleep

I salivate for food as if I’m starving

Full belly tells a different story

I wonder if the lessons that you taught me come in handy

For when I want love to see me in my shadow

For when I’m dressed up like a clown with rainbows of beige and browns

I don’t eat fruit because it feels too good

Sugar is the same as when I cry and smile and taste the

salt lake house you left me in

I am an old one because you the ancient were inside me

You implanted all your heart and now whenever I love

I wonder if you love it too

I’ve regrown all my teeth

I’ve shoveled out the dirt

I’ve planted all new trees

I am a garden in full bruise

Artist’s Statement on the photos: The pictures are from the Full Moon on December 11, 2019. They were taken inside Joshua Tree National Park.

Ingrid M. Calderon-Collins is an immigrant from El Salvador. Her work has been featured in Thimble Literary Magazine, Rabid Oak, Moonchild Magazine, and FIVE:2:ONE amid others. She was the hostess of a monthly poetry reading series, “They’re Just Words” featuring poets from all over L.A. County from 2017-2019. Currently, she runs a literary magazine called “RESURRECTION mag,” where she encourages poets, artists and photographers to show the world their joys and their sorrows. She is the author of thirteen books. She lives in Los Angeles, CA with her husband, painter John Collins.

Photo: Joanna C. Valente

Grief Before Grief

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, Sexting Ghosts, Xenos, No(body), #Survivor (The Operating System, 2020), and Killer Bob: A Love Story (Vegetarian Alcoholic Press, 2021). They are the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault and the illustrator of Dead Tongue (Yes Poetry, 2020). They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College, and Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine.

Read MoreA Playlist for The Magician

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of Sirs & Madams, The Gods Are Dead, Marys of the Sea, Sexting Ghosts, Xenos, No(body), #Survivor (The Operating System, 2020), and Killer Bob: A Love Story (Vegetarian Alcoholic Press, 2021). They are the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault and the illustrator of Dead Tongue (Yes Poetry, 2020). They received their MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College, and Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine.

Read MoreImage by Lisa Marie Basile

autumn beloveds: DIY Moon Water Space Cleansing Spray

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

For the entire month of October, I will be posting daily to Luna Luna about all things magical, witchy, spooky, and spoopy. From books and tarot decks to films and random research or rituals I happen upon, I’ll be offering up a little taste of the shadow.

Today, I wanted to share something that I make to cleanse my space of negative or stagnant energies — and to protect it. Since I live in an apartment (and anyone who lives in a city or an apartment knows how many disparate energies and feelings are floating around) it is often easier for me to do this than to use smoke. I also just adore the ritual of it.

Before engaging in ritual or any sort of sacred act (like journaling or visualization) it’s a good idea to cleanse yourself — and the space of any dull or stagnant or harmful energies.

An easy-to-make apartment-friendly space-cleansing elixir

You’ll need:

Large bowl or mason jar of water

Organic herbs (especially those bought locally or those which are embraced by your ancestors or practice; I like to use rosemary — for its cleansing properties — or lavender — for its soothing and healing scent) or organic essential oils. Try to ethically source your goods if possible and be mindful of pets and roommates’ allergies.

A water-safe crystal (optional) that I’ll use is rose quartz —to promote love in your space — or clear quartz (within the water) — to clear negative energies.

A few pinches of salt (any salt will do; many use coarse or sea salt as it’s often on-hand, and some use black salt, which is said to absorb negative energies). Salt is oft-used in protective and cleansing acts across practices.

A spray bottle with an atomizer. I like to use glass, but anything will do. You can also keep the water in a jar (I also do this often) and use your fingers to spray the water; some of us also like to be physical and use our hands.

Let the water sit under the moonlight for a whole evening (if you live in an apartment, a windowsill or hidden area where it won’t be disturbed will do). You may place a crystal within the water to soak up the energy of the crystal. Cover the jar or bowl. When placing it under the moonlight, I always ask that the water be blessed and programmed to cleanse, protect, and purify my space.

You can say this (or, better yet — of course — write your own incantation!):

May this water be blessed by the light of the moon; that it becomes as the moon is — luminous, capable of the tides of change. May this water be used to cleanse, purify, and create harmony in my space.

PS: You can write this out and tape it to the bottle, too, or draw a sigil on the bottom of the bottle.

Oh, and direct moonlight is hard to come by; my window really only faces another building. If you can’t find the moonlight, just having access to the night sky is enough. In the morning (it’s okay if you get up after dawn breaks, though some folks get up before the first light), collect the water and pour it into a cleansed bottle.

You may drop a few drops of essential oils (careful with pets) or stick a few sprigs of herbs into the bottle. If you have a small enough crystal, you can drop it in as well. Use this spray when the energy, air, or ‘traffic’ becomes stuck, stagnant or tiresome. I recommend opening a window and using this spray elixir in each room and space you inhabit — especially before a ritual or journaling. You can even keep a smaller bottle near your door — with which to spray upon your being when coming in from outside.

Of course, any intentional act is only made better with beautiful, intentional words. If you were to recite an incantation every time you used the spray, what would you say?

You might start with: With this sacred water, this space becomes______, free from _______.

Lisa Marie Basile (she/her) is a poet, essayist, editor, and chronic illness awareness advocate living in New York City. She's the founder and creative director of Luna Luna Magazine and its online community, and the creator of Ritual Poetica, a curiosity project dedicated to exploring the intersection of writing, creativity, healing, & sacredness. She regularly creates dialogue and writes about intentionality and ritual, accessibility, creativity, poetry, foster care, mental health, family trauma, healing, and chronic illness. She is the author of THE MAGICAL WRITING GRIMOIRE, LIGHT MAGIC FOR DARK TIMES, and a few poetry collections, including the recent NYMPHOLEPSY, which is excerpted in Best American Experimental Writing 2020.

Her essays and other work can be found in The New York Times, Narratively, Sabat Magazine, We Are Grimoire, Witch Craft Magazine, Refinery 29, Self, Healthline, Entropy, On Loan From The Cosmos, Chakrubs, Catapult, Bust, Bustle, and more. Her work has been nominated for several Pushcart Prizes (most recently for her work in Narratively). Lisa Marie has led poetry, writing, and ritual workshops at HausWitch in Salem, MA, Manhattanville College, and Pace University, and she's led ritual and writing events, like Atlas Obscura's renowned Into The Veil. She is also a chronic illness advocate, keeping columns at several chronic illness patient websites. She earned a Masters's degree in Writing from The New School and studied literature and psychology as an undergraduate at Pace University. You can follow her at @lisamariebasile