Etel Adnan, Tizio Fratus, Nicelle Davis, Leah Silvieus

Read MoreA Look Back at AWP 2016 Through Caramel-Colored Glasses

BY MIGUEL PICHARDO

Outrage is exhausting. Three-day conferences in a different time zone are just as taxing. With plenty of collective outrage leading up to the 2016 AWP (Association of Writers and Writing Programs) Conference in Los Angeles, I had to conserve my energy.

I understand that there was plenty to rail against—culturally-deficient committees, poor accessibility, the tactless exploitation by Vanessa Place made worse by Kate Gale’s ranting—but I didn’t travel across the country to be swept up in polemics. When holding a conference in such melting pot of a city whose history has been marred by racial tumult, the Association could no longer afford to ignore the groups they’ve alienated in past years. And I couldn’t bring myself to knock the Association for trying. So, I loosened my brown fist into an open hand, tucked my soapbox under the table at my lit mag’s exhibit, and prepared to make the most of a conference where, for once, I felt welcome.

If you’ve ever been to an AWP Conference, you know that there are so many panels and events going on at the same time that you might wonder how far human cloning technology has come in recent years. Had I a team of extra Miguels, I would’ve attended everything on the schedule that spoke to me as Latino writer of poetry and fiction—maybe. Here’s some of what one Miguel managed to catch at the 2016 AWP Conference:

Panel Discussion: “Creating Opportunities for Writers of Color: A Continued Urgency”

Seated at the head of a hotel conference room were Reginald Flood, Diem Jones, Elmaz Abinader, Angie Chuang, and Angela Narciso. All of these authors have in one way or another dedicated their writing lives to circumvent “the perils of publishing in white institutions.” Abinader and Jones are two of the four founders behind VONA Voices, the only writing conference/workshop in the US that focuses on multi-genre work produced by writers of color. As of last summer, VONA left San Francisco and has made Miami its new home. Flood, Chuang, and Narciso have been involved with Willow Books, an independent press that strives to promote diversity in publishing by recognizing outstanding writers of color.

The panelists asserted that, as a community, writers of color can work towards creating an “alternate canon” worthy of inclusion in national and literary discourse. The aim then is not “diversity”—a word the panelists agreed is white, politically correct code for racism—but “equity,” as put forth by Narciso. Chuang then spoke on how writers of color should avoid becoming monoliths, self-absorbed loners who have forgotten that art can build bridges between communities.

When Jones pointed out that traditional pedagogy sometimes doesn’t work for writers of color, I realized that instead of writing for just anyone who will read our work, we should be writing for readers of color instead. Before I penned my first poem, I was an English major who couldn’t stomach the Bard and whose aspirations were forever changed after reading Junot Diaz’s Drown. I didn’t find this collection in any classroom; it switched hands between me and some of my Dominican friends at St. John’s University. I then passed it on to a group of high school students I was mentoring at the time. Re-education is not only possible; it’s necessary if we wish to turn the status quo on its head.

Before fielding questions from the audience, Abinader urged the writers of color in the room to fill in the “hollowness of diversity’’ by nurturing their individual voices and to always “make them [white people] uncomfortable.”

Will do, Elmaz. After all, change is hardly change unless it’s uncomfortable.

Reading: “Throwback Thursday: Four Forms of Performance from the Early 90s Nuyorican Poets Café”

Four years ago, when I still lived in New York, I’d often check out a reading or a slam contest at the hallowed literary hub that is the Nuyorican Poets Café. I’d sometimes take my high school students along as a field trip. More than once, they left the café so inspired that they’d recite their own poems on the R train back to Queens. The panel at this year’s AWP showed me that the Nuyorican still has that same impact on young poets.

An institution of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, the Nuyorican has been home to a community of poets since 1975. The AWP readers—Xavier Cavazos, Ava Chin, Crystal Williams, and Regie Cabico—represented a living snapshot of the Nuyorican’s 90s heyday. Since then, they’ve earned fellowships and PhDs, won national slam competitions, appeared on HBO’s Def Poetry Slam and NPR’s Snap Judgment, and of course, published multiple books. However, they all agreed that none of their achievements would’ve been possible without the Nuyorican, their “first MFA.”

Each poet recited a piece and followed it with some recollection of what the Nuyorican did for them as budding artists. Cabico, a queer Filipino American slam poet, said that without the Nuyorican he would have been a massage therapist or a lawyer. Chin credited the Nuyorican with giving her the space to explore language as a first generation Chinese American. Williams broke down the three lessons she learned about slam at the Nuyorican:

1. If you’re going to read a poem, then read a poem. Make sure that it has all the craft and technical considerations that go into creating poetry that is meant to be read aloud.

2. Slam with the intention to connect with your audience.

3. Come original. Be your full-throated self.

Last, and most memorable, was Cavazo’s reading. Taking a cue from Williams’ lessons, he launched into a hilarious poem titled “Motherfuckers” without the delay of unnecessary preamble. The piece was a tirade against Miami Marlins’ former manager, Ozzie Guillen. No matter where I go, the 305 follows. But his poem is not what stuck with me. Recalling his days as an addict, Cavazo said he owes his life and his sobriety to the friends he made within the Nuyorican’s brick walls, his fellow panelists. Teary-eyed, he reminded us that, “Slam is not an aesthetic; it’s a community. Keep it whole. Keep it beautiful.”

A Q&A followed, unlike any I’d ever seen. A Japanese American teen from Orange County raised his hand not to ask a question, but to make a request. He had a slam competition coming up, and was wondering if he could practice his piece for the audience. The panelists could not have been happier to oblige and invited him on-stage. As he read, I was reminded of my students back in New York. It was a relief to see, to hear that the oral tradition of slam poetry is alive and well from coast to coast, as relevant today as it was in the 90s.

The Latino Caucus

This year, the Association’s efforts to be more inclusive were apparent without coming off as pandering. Special accommodations were made for disabled attendees and panel titles were rife with acronyms like WOC and LGBTQ. The most apparent reforms could be seen in this year’s caucuses. At the end of the conference’s first two days, caucuses were held where groups of writers communed to discuss the challenges and opportunities their demographics face in the current publishing landscape. Caucus groups included writers in low residency MFA programs, Indigenous American writers, Asian American writers, and writers in recovery. One caveat about these caucuses was that many were held simultaneously. So someone who identified as say, a queer woman who teaches high school, would’ve had to prioritize one of these identities as her way into a larger community of writers.

I attended the Latino caucus where each panelist represented a different facet of the literary world. Emma Trelles, an alumna of FIU’s MFA program, spoke for the journalistic obligations a community of Latinx writers has in order to foster an atmosphere of good literary citizenship. She urged us to query editors for reviews on books by Latinx authors, and to cover each other’s events. Francisco Aragon, director of Letras Latinas at Notre Dame, suggested ways we can foster relationships with existing institutions in order to create literary programming and events focused on works by Latinx authors. Co-founder of the poetry workshop CantoMundo, Deborah Paredez invited us to “self-interrogate” in our work as a means of surveying the isolation we experience inside and outside of institutions. Moreover, she reminded us that “we are not exceptional Latinos; we’re representative of them.”

Lorenzo Herrera y Lozano, editor of several Latinx anthologies, posed the important question: “What would it take to publish ourselves into being?” The answer was provided by the following panelist, Ruben Quesada. Representing the literary magazine world, Quezada has held decision-making positions for publications like Codex Journal and the Cossack Review. Whenever he noticed a lack of Latinx representation in literary magazines, he either started his own or changed a predominately white one from the inside through what he called “deliberate editing.”

Quezada’s talk resonated with me especially. As the Latino editor of a literary magazine, I’d love to edit deliberately, but we simply don’t receive too many submissions from Latinx writers. During the Q&A, I made this known to a room full of strangers who looked like me, who spoke my first language. Before the Latino Caucus was over, my magazine’s Facebook page saw a surge in likes and the inbox was hit with questions about submission guidelines and book review queries.

If that’s not community, I don’t know what is.

Despite the overwhelming kinship and empowerment I felt in that room, I knew this could be the first and last Latino Caucus to ever be held at an AWP Conference. Sure, Latinx authors are as visible as ever, but being visible and being sustainable are two different feats. Before this caucus becomes an annual event, the Association asks that we jump through a series of hoops. For one, there must be panelists to preside over future Caucuses, each of whom have to have attended the last three consecutive AWP conferences as paying members. Also, the Association wasn’t concerned with how many people attended the Caucus; they just wanted the minutes when it was over. Only after the third Latino Caucus, to be held in 2018, does it become a permanent panel on the conference schedule.

Regardless of the shaky foundation the Latino Caucus stood upon, I still felt that I’d found my literary tribe, one I never knew could be available to me.

Off-site Event: The Bash hosted by The Conversation

This event could not be found on any official AWP listing. Invite only. I came as a dear colleague’s plus one. After enduring a lame, ill-planned reading, we called an Uber to take us to Ladera Heights, AKA the Black Beverly Hills. Live drums and saxophones could be heard as we pulled into the driveway of one of the nicest houses I’d ever been invited to. We were greeted at the door by our co-host’s father, Mr. Barnes. Inside, the rooms were adorned with paintings and wall-to-wall bookshelves brimming with knowledge. I imagined that this must’ve been such a nurturing environment for a poet like Aziza Barnes to call home.

I leaned over to my colleague and whispered, “I wish Mr. Barnes was my dad.”

Mr. Barnes gave us the lay of the land: where to find the booze, the coffee, the snacks, and the pièce de résistance, the taco bar. The hospitality was on one hundred thousand; I was exactly where I needed to be.

The band played Motown classics as I made trip after trip to the taco bar. I spoke with young black, white, and Latinx poets from all over the country. I even reunited with a poet from Mississippi I met during the 2015 conference. We agreed that the Association had taken the hint since last year in Minneapolis, where the melanin-deficient panels and attendees made us seriously question what we were doing there in the first place.

I struck up another conversation with a black poet and PhD candidate from Flint, Michigan. Maybe it was the festivities, but like me, he was overjoyed to see so many writers of color sharing such a memorable night. He told me about Claudia Rankine’s moving keynote address, which I’d missed the night before. We exchanged email addresses and poems. The band played their last notes and then we heard the announcement, “They’re going to read.”

An unveiling was upon was, the reason why we’d all come together. Nabila Lovelace and Aziza Barnes had organized The Bash as the joyful inauguration of a new literary institution they’d founded and dubbed “The Conversation.” The organization’s mission is to “carve out a space for Black Americans to contend with their Blackness and its infinite permutations in the South.” Lovelace and Barnes wanted to turn the literary conference model on its head, and by throwing The Bash, they had done so beautifully, in a manner no POC I know could resist: the house party.

Our hosts stood silently in front of their mic stands, commanding us with their presence before either of them spoke. Lovelace’s head was wrapped in a soft cloth and Barnes wore a plaid blazer, dreads draped over her shoulder. Barnes thanked all of us for attending and stressed the importance of coming together outside of the Association’s confines. She went on to read a poignant piece about being harassed by LAPD outside of the very house we were gathered in—the house she grew up in.

After the reading, the band packed up their equipment. Yet, the party was far from over. A DJ set up his gear and turned the Barnes living room into one of those basement parties from my high school days. The lights were low, the floor was shaking, and bodies moved to anthems like Montell Jordan’s “This Is How We Do It” and Juvenile’s “Back That Azz Up.” When Dark Noise Collective poets Danez Smith and Nate Marshall busted out a flawless “Kid ‘n Play” in the middle of the dance floor, the crowd lost it.

I swayed to the music, getting by on my two left feet and reveling in the ruckus we were busy making. Amid a conference that was anything but silent, the noise of change had been a low hum since I arrived in Los Angeles. Here, at The Bash, it reached its crescendo.

The DJ threw on Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright,” and played it loud. All of us chanted the chorus together, “We gon’ be alright/ Do you hear me, do you feel me? We gon’ be alright.”

I couldn’t agree more.

Like this article? You should try: Breaking the Cultural Ties That Bind Us

Miguel Pichardo is a Dominican/Ecuadorian writer out of Miami. His poetry has appeared in Duende and Literary Orphans. He is currently an MFA candidate at Florida International University and the editor of Fjords Review.

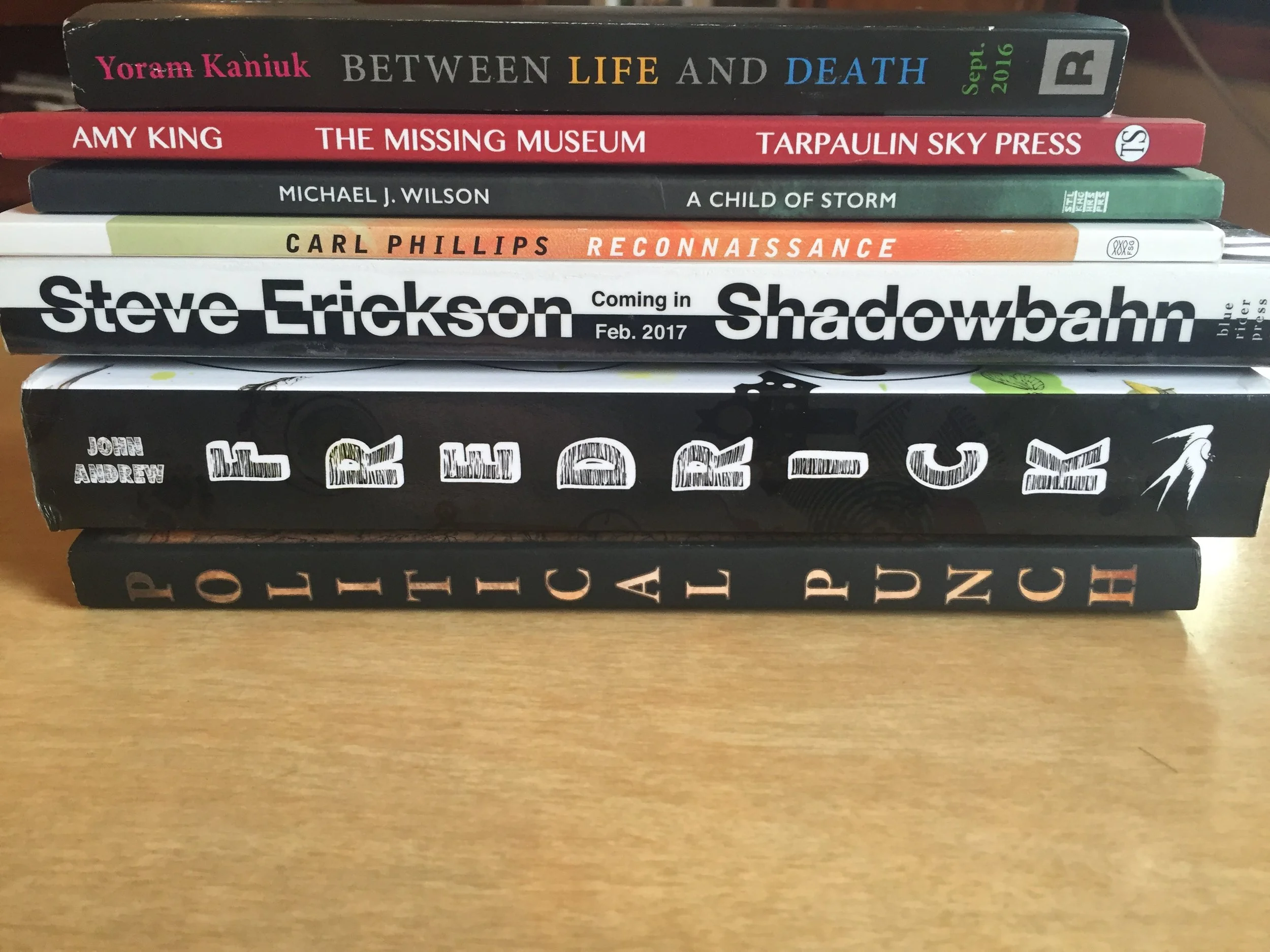

7 Books You Should Read If You Want to Be Human

BY JOANNA C. VALENTE

1. Between Life and Death - Yoram Kaniuk (Restless Books, 2007/2016)

Excerpt from Lit Hub:

"Near the house, right across from the calm hidden beauty where I searched for a gutter to play me the lullabies of my childhood, a little bit of sea is still open. Moshe my father would swim in it every day at exactly five in the afternoon, after most of the swimmers had already gone home, because he loved having the sea all to himself. In the spring and fall, the sea was sparkling and smooth and soft, and sometimes in the morning, on the way to school, we’d walk barefoot in the sand along the shore, and under the hewn-limestone wall, we’d take off our shoes, hang them by the laces on our shoulder, put our schoolbags on our heads like the Arab women who carry ewers of water and bundles of wood to the ovens, and we’d walk in the shallows lined with seashells, some were broken and cut our little feet, until we came to the sand dune across from the Model School."

2. The Missing Museum - Amy King (Tarpaulin Sky Press, 2016)

From TS' site:

"AND THEN WE SAW THE DAUGHTER OF THE MINOTAUR

Poet, comma. It is thus the delay,

which is also a beginning. That we can link eyes

across her time-space continuum is another hyena.

The female elongates, bares fangs, and a trash

compactor recycles. Hyena gives

in the recycling fashion. Phoenix, no more false

flight from holes; now balloons eating decay.

Hunger denuded us, too. But will you give

up your death for me? With surgery, I outright hollow

the monster to breathe across windows. I don her hollow

whole. She writes back in the pauses of haze.

Her and her tragic magic. We are all cross-dressing

in tiny wings with the machines of bones to go on."

3. A Child of Storm - Michael J. Wilson (Stalking Horse Press, 2016)

Sensitive Skin Magazine published four poems from the collection:

"Edwin Davis & The Electric Chair

Brown came with a crate.

The kind milk bottles condense in.

He sat it down. In the center of the room.

I had spent the day clearing cobwebs, a rug.

I used parts of the crate to make the chair.

Stringing the wires, using the Edison diagram

The Brown instructions.

I shot 1000 volts through Kemmler

then again until he burst to flame.

The skin around the metal became leather.

They would have done better using an axe.

I shot volts into a woman. Into the man who shot McKinley.

I got to meet J.P. Morgan. Twice.

Every time –

The smell –"

4. Reconnaisance - Carl Phillips (FSG, 2015)

ead an interview with Phillips at NPR:

"I have, from the start, been writing about the body and power. And maybe more specifically, the gay male body, and power in intimate relationships, but I feel as if there's a lot of overlap with society's views of how different bodies are treated. So to that extent, I think there's always a kind of political resonance to the personal, and then vice versa."

5. Shadowbahn - Steve Erickson (Blue Rider Press/Penguin, 2017)

It's exactly what we need right now - a book set in a tragic political landscape along to a playlist to give song to the time we live in now - one of strange turmoil and uncertainty. All of the characters are on a journey of self-discovery, and the reimagined Twin Towers represent this. It's definitely a book to pick up once it's released this February.

6. The King of Good Intentions II - John Andrew Fredrick (Rare Bird Books, 2015)

Read an interview with Fredrick at LARB:

"I think the books are failures too. Brilliant failures, of course. And again I don’t mean brilliant in the look-at-me sort of way, but brilliant in the sense that parts of them (and I hope the preponderance of them) truly shine. As comedy. And very very human and humanist. Isn’t that enough? Yes, I revised the first King five times. The hardest work I have ever done. Much harder than writing a dissertation on Ford Madox Ford and Virginia Woolf. I just got sick of looking at The King II, I revised it so much. I’m a Jamesian and a Joycean. I could revise all day — trying to lift the prose into poetry, trying to make the jokes zanier and tighter. There’s nothing wrong with failing. Failing is an energy. And in a way, paradoxically, the books are not failures and I am being very disingenuous about the records. You shouldn’t trust me; I’m an unreliable narrator in real life, too."

7. Political Punch: Contemporary Poems on the Politics of Identity - Edited by Fox Frazier Foley & Erin Elizabeth Smith (Sundress Publications, 2016)

Read an interview with both editors over at VIDA about how the anthology came to be. Foley stated:

"My feeling about this are complicated, and kind of conflicted. I think of poetry in the same way that I think of prayer. I’m a religious person, so to me, prayers are actually a significant factor in seeking any type of progress, including political or social progress. Prayer and poetry, to me, are both ways of centering your consciousness, and raising both your focus and your energy. They are both, on some level, ways of howling down the parts of the Universe that we don’t entirely understand (I mean, we might name them, or tell stories about them—but I think all religious apparatus is really just a way of making somewhat intelligible to us the forces that are beyond our rational comprehension) to please come to our aid in helping us fix this situation. Prayer and poetry both bring people together, too—one person’s words can forge connections among many people, so that ultimately both a poem and a prayer can result in focusing the energy and consciousness of larger groups, in a way that creates a feeling of solidarity. To me, all of that is integral to political and social progress. I understand that not everyone sees it that way, but speaking for myself and my own lived experiences, that’s how I understand it."

CA Conrad's poem in the collection is amazing; excerpt from “act like a polka dot on minnie mouse’s skirt:”

"i am not a

family friendly

faggot i tell

your children

about war

about their tedious future careers

all the taxes bankrolling a

racist tyrannical military."

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. She is the author of Sirs & Madams (Aldrich Press, 2014), The Gods Are Dead (Deadly Chaps Press, 2015), Marys of the Sea (forthcoming 2016, ELJ Publications) & Xenos (forthcoming 2017, Agape Editions). She received her MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. She is also the founder of Yes, Poetry, as well as the managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of her writing has appeared in Prelude, The Atlas Review, The Huffington Post, Columbia Journal, and elsewhere. She has lead workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente

via Women of Faith

Poetry by deziree a. brown

deziree a. brown is a black queer woman poet, scholar, activist and self-proclaimed “social justice warrior” from Flint, MI. They are currently a MFA candidate at Northern Michigan University in Marquette, MI, and often claim to have been born with a poem written across their chest. Their work has been recently published in the anthology Best “New” African Poets 2015, Duende, Crab Fat Magazine, and Razor. Twitter: @deziree_a_brown

Read MoreAdrien Coquet

Poetry by Meg E. Griffitts

Meg E. Griffitts' work has appeared or is forthcoming in Hypertrophic, Evening Will Come, The Colorado Independent, andBlazeVOX.

Read More#TrumpTapes Erasure, Poetry by Meghann Plunkett

Meghann Plunkett is a poet, performer, coder and feminist. Her work has appeared in national and international literary journals including Muzzle Magazine, The Paris-American, Simon & Schuster's anthology Chorus, and Southword. She teaches creative workshops at Omega Institute and co-directs a children's summer camp called Writers' Week Aboard the Black Dog Tall Ships in Martha's Vineyard. Currently, Meghann is an MFA candidate at Southern Illinois University.

Read Morevia Shutterstock

This is What it's Like to Come Out Online — in 7th Grade

I didn't know any women who were gay or bisexual. I didn't know who to turn to for advice.

Read MoreInterview with Michael J. Seidlinger on GIFs, Gender & the Apocalypse

Everyone seems to know who Michael J. Seidlinger is, even if just by name. Seidlinger is a ghost — the kind of ghost who messes up you book case and reorders everything so you can't actually find what you're looking for. But then when you actually look back at all of the reordered books, you find something beautiful stuck in there that you hadn't seen before.

Read MoreEl Yas

Portrait of a Fat Girl

Sometimes, I feel sad when I look back through old photo albums. There are so few of me beyond the age of 12 that it is occasionally difficult to even remember what I was like then. What happens, because I am so undocumented, is that all I remember is being sad, fat, unhappy, uncomfortable. I know that’s not how I felt every day. Yet, it’s all I’m left with.

Read MoreWitchy World Roundup - October 2016

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. She is the author of Sirs & Madams (Aldrich Press, 2014), The Gods Are Dead (Deadly Chaps Press, 2015), Marys of the Sea (forthcoming 2016, ELJ Publications) & Xenos (forthcoming 2017, Agape Editions). She received her MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. She is also the founder of Yes, Poetry, as well as the managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of her writing has appeared in Prelude, The Atlas Review, The Feminist Wire, BUST, Pouch, and elsewhere. She also leads workshops at Brooklyn Poets.

Read MoreJohn Silliman

How I'm Navigating 'Being American' as an Immigrant & Mom

The USA vs. Netherlands women’s soccer friendly is about to kick off. We are at the Georgia Dome in Atlanta, seated close enough to discern the revved up expressions of the players on the field. It is the first time my 10-year-old daughter, a soccer player, and I, the quintessential soccer mom, are watching a pro team up close.

Read MoreShun Takino

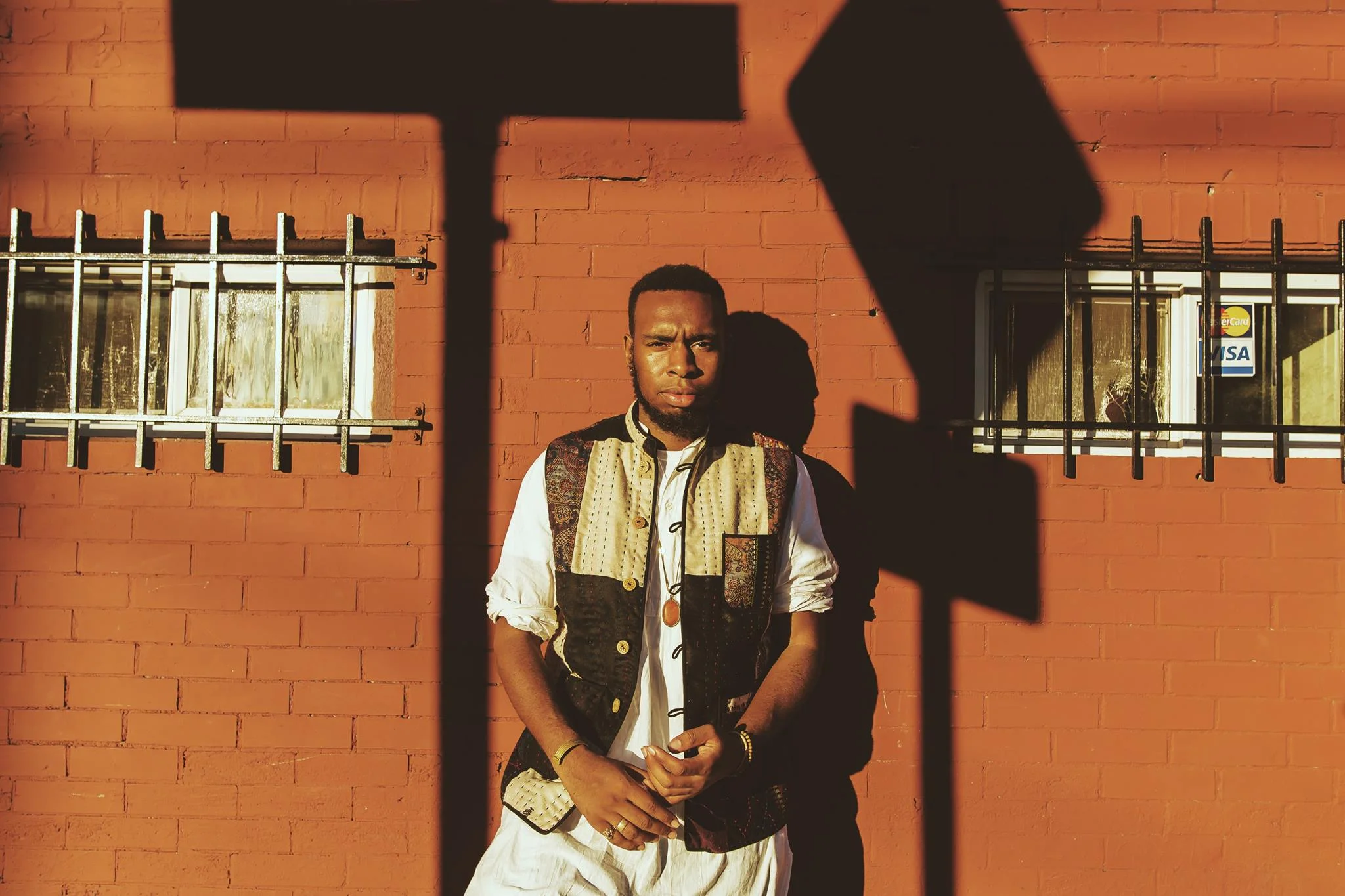

Interview with Musician & Poet Marcus Bowers on 'First Kiss'

Marcus Bowers, also known as Lateef Dameer in music circles, is a force of nature. He blends music and poetry together seamlessly. He collaborates with poets and writers to create music alongside writing (which you can listen to here) with the collective Brooklyn Gypsies. Over the past few years, Bowers has been working on "First Kiss," which is best described as a music, poetry, and documentary album, Bowers wrote lyrics, recorded music, and interviewed people on what they think love is. And that's a question worth asking - and answering.

Read MoreInterview with Sweta Srivastava Vikram

In 2013, Indian poet Sweta Srivastava Vikram published a collection of poems titled No Ocean Here. Published by Modern History Press, No Ocean Here documents the stories of oppressed women living in different parts of Asia, Africa and the Middle East. Following an itinerary made up of narrative poems, the reader travels to countries including Singapore, Bangladesh, and Cameroon, coming face-to-face with patriarchal tyranny. Vikram takes her readers on an emotional and geographical journey. She writes,

I walk humbly through cultures,

documenting stories

for women without a voice.

-"No Ocean Here"

Where Were All The Feminists When Amanda Knox Was On Trial?

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

This was originally published at The Huffington Post.

This was republished here as a sort of accompaniment piece for those of you watching Netflix's new documentary, Amanda Knox, which aims to uncover why the public turned a straight-forward case into a pit of sexism and injustice.

Amanda Knox is innocent of murder.

As a reader, you may have already chosen a side, since some have made this a battle of culture and evidentiary ping pong. Either you agree with my assertion of innocence or you don’t, but there’s a bigger social issue at play here: People’s lives are being ruined by sexism and lies.

I am making an appeal to all feminists and people of rational thought: We need to speak out, regardless of our beliefs. Beyond the fact that no credible or realistic evidence places Knox or her then-boyfriend Raffaele Sollecito at the scene of Meredith Kercher’s murder, Knox’s very average sexual behavior and our sexualization of her image should not be spearheading the campaign against her.

When I ask people what they think about the case, most of them say, “It’s obvious to me that she is innocent!” yet rarely do people discuss the treatment of Knox or the impact this case will have on others or society in general. Why is it OK to lie to someone about their having HIV only to attain a list of sexual partners which would then be leaked to the media? This is an example of systematic character defamation — the modern equivalent of throwing an accused witch into the lake to see if she drowns. What sort of pain must we put others through in order to forge our own versions of the truth?

Let’s pretend for a moment that Amanda Knox is guilty. Would her sexual partners or attractiveness matter? No. All that would matter is her culpability; you certainly don’t need to be pretty to commit murder. But the fascination and objectification of Knox’s "bad-girl" persona (when purposefully created and pitted against Kercher’s "good-girl" persona) has constructed a sort of cinematic set of lies. Is Italy afraid that a good-looking American girl actually isn’t a threat to the very fabric of modern society? It seems yes.

Knox and Sollecito’s lives will doubtfully be untainted by this miscarriage of justice, but we still can learn from the case. First, though, we should know how not to talk about it.

Just a few days ago, Jezebel — a blog for women — published a piece, "The 12 Ways We Are Amanda Knox." While the author, Tracie Egan Morrissey, believes Knox is innocent, the article is silly, lazy and downplays the significance of the issue. I have hope that feminist journalists will start taking this case more seriously. I have hope that we will consider the repercussions of sexism when we take to social media to discuss the case. I have hope that we can look past pot and sex.

If that seems judgmental, it’s because we as a society — and perhaps we as feminists — have failed Amanda Knox. People ask me why I care about this case. It is because I am a human and a feminist.

In 2007, Knox was being held in — and consequently convicted to — an Italian prison cell until her 2011 acquittal (she is now convicted again). In 2007, I was in college and I’d seen the headlines — things like Satanic Ritual Gone Wrong and Gory Sex Game Leads to Murder. I remember thinking, this just doesn’t add up. There’s no basis for this assumption! They said she was a liar, which reminded me of a time when I was much younger and dealing with a legal case. While my experience had nothing to do with murder, I was, for all intents and purposes, considered a liar, a young girl with a bad M.O. I was slut-shamed for reporting a child-molester. She has to be lying. She wanted the attention, they said. She made the other girls lie, too.

Why are we, as a society, so quick to sexualize and blame victims on the very basis of gender? Why must we live by some imaginary angel/whore binary?

This case jolts me in other ways as well. As an Italian-American, I am ashamed and saddened that this fiasco has painted, for some, a revolting picture of Italian culture. Italians aren’t barbarians without a sense of logic, but this case isn’t helping the image. The trial of Knox and Sollecito has exacerbated the idea that many Italians are operating a witch-hunt run by stubborn, macho and misogynistic character-assassins. I cannot help but agree.

When Italian authorities celebrated the capture of Kercher’s murderer early on in the trial (due to Knox’s forced false confession, which implicated her employer Patrick Lumumba) the Italian "authorities" were revered as heroes. They had "solved" the case! They had brought justice to poor Kercher, whose bloodied, battered body called for peace. More so, and perhaps more importantly, they had caught the attention of the world, who watched as the small, rustic city of Perugia closed the case on something truly awful.

Couple this false "triumph" (it was not Lumumba after all, but Italy was already boasting) with botched forensic analysis, undeniable Italian nationalism and a bad feeling about a pretty American girl, and you have a media circus.

The prosecution’s theories have changed and morphed over the past seven years; they’ve included sexual and Satanic motives (thanks to Mignini, the God-fearing prosecutor who has been known to use psychics as part of investigations), disputes over housework and personality and a spontaneous desire to kill. Just because the newest claims include a murderous "quarrel" involving stolen money doesn’t mean we should forget the storm of sexism that set the tone for the case.

Just last year CNN journalist Chris Cuomo glibly asked Knox on national television if she is a sexual deviant, and a California porn company offered her $20,000 to star in a sex flick.

"As you may have read, and were most likely well aware of, the general consensus is you are absolutely smoking hot," Michael Kulich, the company’s founder, wrote.

This offer made the news, sure, but the sad matter is that it barely shocked anyone. This is a woman whose life has been turned upside down by a wrongful conviction, and all we can think to do is comment on her looks? If Kulich sat in prison for four years for a crime he didn’t commit, would he think his gesture so clever?

Like all murder cases, the facts should dictate the proceedings. The defendants shouldn’t have to go on trial for their lives, their interests and their sexuality — especially when it doesn’t relate to the crime. But this isn’t a normal murder case. This is an inquisition.

One fact — perhaps the only fact we need to know — is that Rudy Guede murdered Kercher. Another fact is that he partied in Perugia and fled to Germany immediately after the murder. Yet another fact was that his DNA was found on Kercher’s body and in the room, while Knox and Sollecito’s DNA was not. Guede admitted to being at the scene.

The DNA evidence for Guede and lack thereof for Knox and Sollecito isn’t magical or a due to a fantastic bleach-clean-up (you can’t see DNA). These are simply facts that have been ignored, manipulated and lied-about, not only by the court but by lazy reportage.

Asserting that Knox and Sollecito casually, you know, joined a criminal for a night of murder-and oh, yeah, maybe a bloody orgy-defies logic and lacks motive. The “facts” have been manipulated to fit the "theory." In this case, 2+2=5.

Just look at this list of Knox nicknames. How is it that most revolve around her sexuality, when Guede is most certainly the rapist and murderer? Knox has been called everything from "evil temptress" to "Luciferina" to "she-devil with an angel face."

Why have we turned her into a filthy, sex-obsessed slut and why aren’t more journalists, writers, advocates and lawyers speaking up about this? Why should Knox have to explain her sexuality to Diane Sawyer?

This seriously flawed case is teaching us that we can be punished for being sexually active or good looking, and that it’s OK to draw parallels between "sexual deviance" and homicide.

This case hinges on not only ignored and circumstantial evidence but preconceived notions and cultural expectations of "the good girl."

First, there’s the case of Knox’s "offness." Salon.com writer Tom Dibblee wrote,

What’s compelling to me about Amanda Knox is that it was her slight offness that did her in, the everyday offness to be found on every schoolyard and in every workplace. This is the slight sort of offness that rouses muttered suspicion and gossip, the slight sort of offness that courses through our daily lives and governs who we choose to affiliate ourselves with and who we choose to distance ourselves from.

When people talk about Knox’s reaction, they’re placing a gendered expectation on her: Should she have been weeping publicly and often? Should she not have kissed her boyfriend? Would only a horrible she-devil derive pleasure while her roommate is dead in the morgue?

How we experience and move-through trauma is personal. It is not up to anyone to determine how one should behave during difficult times. Knox was 20 years old, an age somewhere between the never-land of youth and the terror of adulthood. Are we, as women, expected to be sensitive, sad and weak? I rarely hear critics discussing Sollecito’s post-murder behavior. So Knox did a split and kissed her boyfriend? I would have done the same.

All other "evidence" is circumstantial or forced.

A grainy CCTV video, "pale eyes," a school-aged nickname and a few sexual partners does not a murderer make. Most women I’ve spoken with have indulged in far more drug use and have had far more sex than Amanda Knox has had, but because this is a modern-day witch-hunt we’re talking about, Knox will continue being one of the most slut-shamed people in major media.

When you search "Amanda Knox" on Twitter, you’ll see just how angry, uninformed and irrational some people are.

And if the public is being fed inaccurate information by the media (because Italy’s judicial system is all about false and circumstantial evidence) they aren’t going to know how to discuss the facts either. Social media has made it easy to report error and exaggerate information, and we should be using it for good. We should be taking a stand against these sexist allegations.

However, sexism isn’t the only problem here. There’s the issue of race — only we’re focusing on the wrong elements.

When people talk about racism and this case, they point to Knox’s naming Patrick Lumumba as murderer. This is understandable without further information. Wrongful convictions based on race are all too common.

We should remember that Knox was interrogated for many hours without food or water. She was slapped and screamed at in Italian — a language she barely understood at the time. When the police found her text message (which said the English equivalent of "goodnight, see you another time") with Lumumba, they psychologically tortured her and coerced her into confessing that he was involved in the murder. If her text message was sent to anyone else of any race, the same would have occurred. She named him because they named him. More so, false confessions aren’t rare. According to the Innocence Project, "In about 25 percent of DNA exoneration cases, innocent defendants made incriminating statements, delivered outright confessions or pled guilty."

The real racial issue is this: Perhaps we wouldn’t even be talking about the Knox case if she wasn’t white and beautiful. This world spins on a white, heteronormative, image-obsessed axis, as does the justice system. In 2011, civil rights attorney Lisa Bloom told Larry King Live that society ought to be outraged by fact that pseudo-confessions and scant evidence would prosecute a young black defendant but slide under the radar of major media. Bloom is right. We need to stop paying media attention to only those cases where white is the central color. We need to be open to our flaws as people and as a system in order to jumpstart any change. We can begin by speaking up.

When we learn how to fairly talk about this trial, we will be able to see clearly — or at least as clearly as possible — through the mire Italy has left in its wake.

Cole Patrick

The Spectator, Nonfiction by Carly Susser

I’m walking with Rob outside a little league field in Hoboken on a Saturday night when a groundskeeper drives up to the curb and disembarks. I trust his red jacket and white hair, his saunter up the grassy hill, and the way he already seems to know what I need.

Read More