INTERVIEW WITH DALLAS ATHENT

LISA MARIE BASILE: Ah, the binary. I am addicted to it and your work explores it so well. It's bikinis versus god and bars versus transcendence and the problematic versus self-empowerment. Except here, the light always seems to win. Was that a conscious choice?

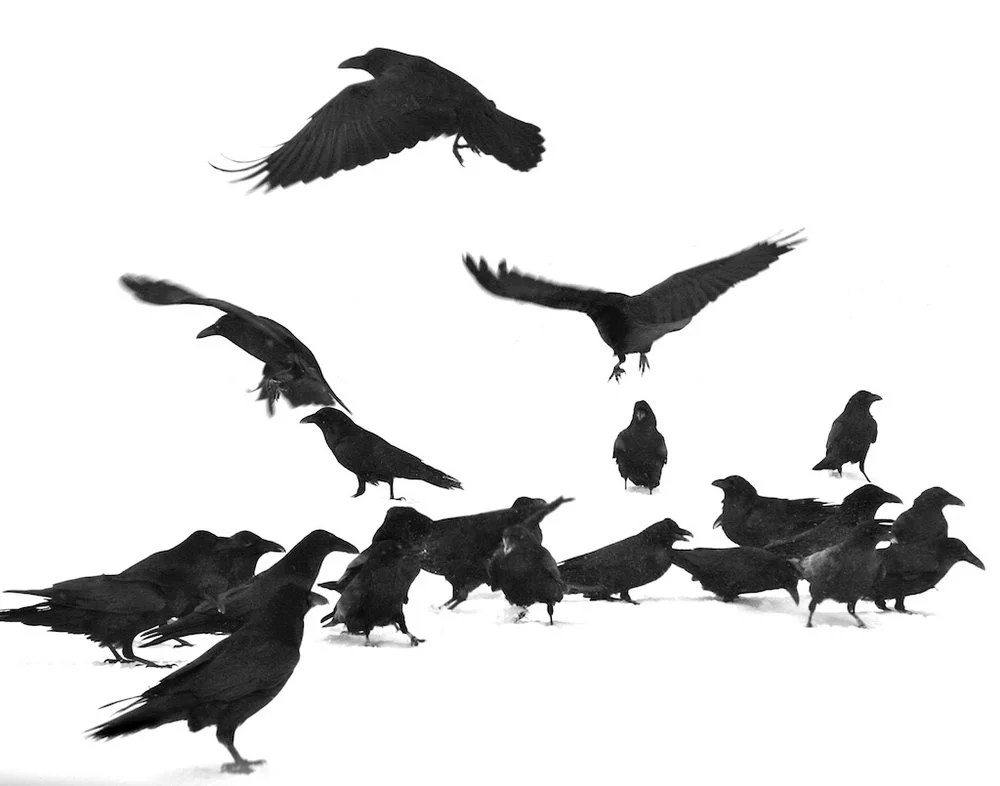

DALLAS ATHENT: I used to believe in good and evil. After my studies ofThe Golden Dawn and Platonic elements, I began believing instead in light and dark. Light elements are things that are connected to the divine, the higher powers, spirituality. Dark matter is that which makes us mortal. It's what drives us to be gluttons. This book is really a study of both states. Light doesn't always win because it is "good," per say, it wins because making art is a struggle for our dark matter to be connected to higher powers.

LISA MARIE BASILE: There's not a lot of subversion here, although on first read I thought there was. I think you're screaming, HEAR ME. And I love it. I don't see a lot of work that encounters radical self strength with such bravado. Tell me, were there weaknesses and fears and vulnerabilities you grappled with while writing this?

DALLAS ATHENT: At one point during this I was laid off from my job the same week I was closing on my apartment. It was a hard week for me and that's where on the one hand I was celebrating an accomplishment, but it felt fake, not knowing if I could really afford this thing I had been working towards. A lot of the darker poems were written during that week, and the ones that are more about me feeling like I can do anything were written when I got myself out of the hole.

LISA MARIE BASILE: So, you keep mentioning England. How did England shape you IRL?

DALLAS ATHENT: I love England. I lived there for a short while and I'm always trying to move back. I adore pub culture. A lot of my friends talk about wanting to visit warm places, and how beautiful beaches are, but for me the most natural state is in the corner of a pub on a rainy day with a book and a pint.

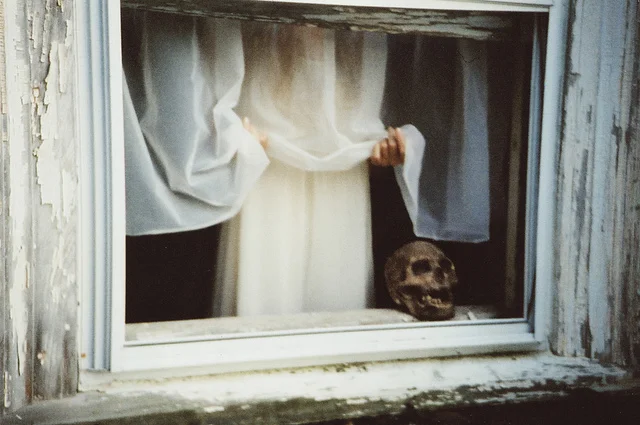

LISA MARIE BASILE: You say, "the purpose of art is horror," and I think that's fucking magic. I agree, but I haven't seen it put so succinctly. Tell me about this idea. Did you aim to horrify?

DALLAS ATHENT: The poem that's taken from is about making art, and trying to leave a mark through doing so. That being the last line was just me thinking of how hard we try and end up nowhere. It's like a beautiful nightmare.

LISA MARIE BASILE: I feel like this book is like if contemporary feminist discourse had a baby with the baddest, most rebellious, most sassy Lana Del Rey video ever. It's all girls and alcohol and scum and the body, but it's elevated with these ideas of divinity and Theia and the powerful feminine. How do you approach talking about BIG IDEAS in such an aesthetic way? I know when I was writing Apocryphal, I wanted this landscape of cars and deserts and fabrics and gardens and beaches and fires and tropics, but at the end of it, that was a character all meant to juxtapose the grandiose shit. What about you? Was this landscape and aesthetic conscious or not? Or was it just, "I love these things. They're real to me?"

DALLAS ATHENT: That's a great question. And I actually feel the same way about Apocryphal. You managed to create this classic, desperate, suburban summer on a coast feel — but used that landscape to illustrate what it's like being a young woman.

For Theia Mania, I've always loved cities and lived in cities. I'm obsessed with places where there's so many people and they all live so close to each other but don't actually know each other and have such drastically different lives. I just like how that contributes to the concept of trying to make art to be someone. It's a constant reminder that we will fade into the fabric of the earth no matter how well known we are.

LISA MARIE BASILE: (Thanks, Dallas). I've heard you talk about Yeats before. You write, "there is an oppressive veil separating us from the stars and Yeats." Can you tell me more?

DALLAS ATHENT: A while ago I read this essay titled the The Gnostics by Jacques Lacarriere. What I got from it was that the Gnostics believed there was a veil that separated us from all that is holy and divine, and that's why mortality is always doomed. Because we're always trying to see everything behind the veil but can never possibly. Yeats, being everyone's favorite Golden Dawn member, and a true inspiration to me, seems to have been someone who has achieved crossing the veil. It was a little line to give him a nod.

LISA MARIE BASILE: What does Theia mean to you?

DALLAS ATHENT: Theia Mania is a Platonic theory about how people who are experiencing horrible things, like heartbreak, are brought closer to the divine in those moments, and that's why we make great art. That state is really what the book is about, along with the dualities of being mortal and immoral, and trying to leave a mark on the world. That's how it got its title.

RELATED: 2 Poetry Books By Women to Read This Summer