Rebecca (Schwab) Cuthbert is a writer and animal shelter volunteer living in Western New York. Her work has been published in Brevity, Slipstream, Treehouse Magazine, and elsewhere.

Read MoreEugéne Atget via The Getty Museum

Eugéne Atget via The Getty Museum

Rebecca (Schwab) Cuthbert is a writer and animal shelter volunteer living in Western New York. Her work has been published in Brevity, Slipstream, Treehouse Magazine, and elsewhere.

Read More

BY SARAH BRIDGINS

I was so excited to sit down and talk to Wren Hanks about their chapbook Prophet Fever, recently published by Hyacinth Girl Press. Prophet Fever is only 16 pages long, but i it Hanks uses the story of the cis gay teenager Wren and his relationships with his destructive mother, a sinister Virgin Mary, and a wolf to explore issues of gender, religion, sexuality, and environmental destruction in ways that are beautiful and complex.

S: First off, how did you come up with the title? I’m just wondering because I love it and I am very bad at titles.

WJ: I’m also really bad at titles and I worked really hard to become better at them. Originally I titled all the poems because there were many poems of varying quality and when I went to put it together, Prophet Fever was the title of one of the more successful poems. It’s section 6. So that’s where the title came from and the reason they’re no longer titles is because the rest of the titles were pretty rote. They were “Becoming” or “What Home Was.” They were pretty plain. When I started putting it together, it felt more like one long poem or sections of one long poem.

S: So when you first started. Did you conceive of this as a chapbook or have you been thinking about it as a larger project?

W: I’ve been thinking about it as a larger project. but I was an MFA and working on other things and it felt like and it still feels like a thing that will take a very long time.

S: Okay, because it works as a distinct piece. It feels finished.

W: Right. It feels like at a certain point I decided not only did I want to have something out in the world but I wanted to see how these poems worked on their own and I felt like I'd reached a certain point in the arc of the story. I could see this character starting off. I could see this kind of anointing and then [my protagonist] goes off to preach and then, it’s like obviously the end of world is coming so you know what’s going to happen—or you can imagine it—and sort of see it spooling out in your mind. My brother is a filmmaker, and I was also thinking in cinematic terms where a lot of times directors who want to make a feature film make a short as a teaser: i.e. if you like this thing I did…there’s more!

S: So when you first started working on Prophet Fever were you thinking of it in terms of a narrative or more thematically because there are all of these recurring images? Did the narrative come out of the theme and the images or what it the other way around?

W: When I first started working on this project, it was very different. It came out of a southern radio broadcast. Mary was the primary character, so it was narrative and I did have a narrative outline that I was working with. It was weird and formal and I feel like it was derivative of a lot of stuff that has been done before. There are a lot of good books that have come out about Mary—Mary Szybist’s Incarnadine and Tracy Brimhall’s Our Lady of the Ruins to name two of my favorites. There has been a lot written about a subversive Mary figure. So I had narrative in mind, but Wren’s character was a lot more minor and peripheral.

S: Wait, so why were you listening to Christian radio?

W: Jeanne, my fiancée, and I do this all the time when we go on long drives. She didn’t grow up religious so it’s something she seems genuinely fascinated by. It’s this alien thing and it doesn’t really upset her because in a way it doesn’t seem real. It’s like reading old misogynist fiction or something. For me it’s harder because although my parents weren’t Catholic I grew up in a place [southeast Texas] where there was a lot of Evangelicalism. I get really prickly about it, but at the same time I have this morbid fascination with the Book of Revelation because Catholics don’t believe in it literally, which I think is interesting. They literally believe that we’re drinking Christ’s blood, but the Book of Revelation is the only book they read figuratively. So we’re driving in this U-Haul from Austin to New Orleans and the whole time we’re listening to these ridiculous stations and there was one of those call-in shows where you donate for prayers. They made $25,000 in ten minutes. The callers were saying, “I’m calling in because I need help because I’m dying of cancer—here’s $100. Or I’m calling in because my son is a homosexual.” Then this incredible man came on talking about how there’s the feast of birds and about how, I don't know the specifics because I haven’t Read revelations in a long time, the people who have been sacrificed and eaten by the beasts are also going to be eaten by birds and the righteous are going to have this supper over their dead bodies. That’s kind of how this book started.

Via Hyacinth Girl Press

S: Did the idea of using all of this as material help you not get as upset by it? Because then you’re approaching it as an anthropologist.

W: It becomes raw material. And I don’t know how much this registers for people who weren’t raised Catholic at all. I’m happy if people just seeit as this weird vaguely religious horror show.

S: You published this chapbook under the name Jennifer Hanks. What is your relationship to “Wren” the character and the speaker and your relationship to”Wren” as the name you later adopted as your own?

W: I’ll start by saying that I’m not the only trans person who has done this which is very comforting because I thought I was and I thought it was very strange. The poet Sara June Woods is someone who has talked about doing this. I know a couple other poets have said they fell into their name by writing letters to this other person. At the same time I don’t feel like Wren is me. I still feel like that Wren is a character. That said, I felt really comfortable in his voice from the get-go, and I kept having these conversations in workshop where people were telling me “That’s not a convincing male character, that sounds too much like you.” and I’m like “What does a male character sound like? And also what assumptions are you making about me that you think I can’t write a convincing male character.”

And this wasn’t my whole workshop experience with this book, but it came up sometimes. But then the chapbook came out and I realized I had been thinking of myself as this name for a long time. I tried to make as little deal of coming out as possible which you know, always goes really well. I didn’t know when I was going to tell my family so I didn’t want to do the name change. The thing about coming out in any way I think is that people want you to make the changes really quickly, or they want to know exactly what changes you’re going to make.

S: Right. And they want to be “good” about it and they don’t want to fuck it up.

W: And a lot of the time you don’t have any idea what the answer is for a really long time. And it hasn’t been a really long time. It’s been like four months. I told a friend, a really close friend who was far away and gende queer that I thought I might do this so they were calling me Wren before anyone else was. I’m still pretty self-conscious about it, and I don’t know how to explain people who don’t know me well. It’s difficult to explain that I feel very separate from the character “Wren,”, but I also don’t think I would have come out if I hadn’t written this or let myself write this.

S: Because then you’re going through the experience of having this other voice in your head, while at the same time it’s still you.

W: It’s a way to ease into being you. And I feel like when you write you do that no matter what you’re easing into. My chapbook that’s just out from Porkbelly is about my grandmother’s suicide and that’s about easing into grief, gender, and all the parts of myself I didn’t get to tell her about.

S: I wanted to talk about the wolf as a recurring figure in these poems. I don’t know if this is a connection, but I feel like the book has all of these sinister maternal figures, and I think of the wolf as a kind of sinister maternal figure just because of Romulus and Remus and that whole connection.

W: That’s there. And I do think of her as a maternal figure. But she becomes the only one who doesn’t have really bad ulterior motives because she’s not human and I don’t know if she’s capable of them.

S: But that’s interesting because she’s the one who is the most outwardly frightening.

W: Exactly. She’s very scary. In the cover image she’s on fire. She’s horrifying.

S: But it turns out she’s the least threatening.

W: Some of that has to do with the initial focus of this chapbook that isn’t as visible now that it it’s character-driven. In the beginning it was more about environmental apocalypse so it was important to me that most of the main characters seemed sinister and it was important that whoever the main protagonist was, they were rejecting the human world in some way. So there’s some of that, but also I think it’s important for Wren to have someone to rely on. He’s rejecting one mother who obviously has a lot of issues so he’s very vulnerable and his new mother figure is not any better at all. I mean, I love her, but she’s a terrible person.

S: Why do you see her as being terrible?

W: I think it’s the same way that the Greek gods’ aims are not focused toward mortals so they can’t really see these people as people. For her the mechanisms she’s working with are so much larger than these individual people involved. So maybe in that sphere she’s moral, but if you’re a person she’s totally manipulative. She totally consumes his whole life.

And it seems like she thinks this is what’s best for him because he’s chosen, he’s going to survive. No one else is, presumably. And you wonder about the reasons why his real mother is deteriorating at that rate and how much that has to do with her.

S: It’s just interesting trading in one dark maternal figure for another one.

W: I feel like there’s this specific queer vulnerability because I feel like a lot of queer kids are growing up through trauma so I’m interested in their ideas of what a family is or what a family might be. I have another chapbook coming out, gar childthat’s about a similar kind of violence, only through generations of queer women. I feel like for Wren maybe this seems like a healthier structure because she [Mary] is strong ,right? And she can actually provide, he’s protected.

S: Another thing I thought was really interesting was the relationship between sweetness and spoil and sweetness and rot. Like with the skinning the hand and the honey, and the meat spoiling, and the bread mold.

W: Well, I’m a vegetarian who is really afraid of rotting meat. I think there’s some sense for me that the natural world encroaching on us is dangerous. For instance, zombie apocalypses are about the breakdown of the civilized (human) world. Zombies are literally decomposing meat bags. Rot is this healthy, functional part of nature that we have a really hard time with. Prophet Fever is also just saturated with the…grossness of teendom. The candy and quick sex.

S: You lived in New Orleans for the last three years. Did you feel like the city influenced the way that you wrote or the subjects that you wrote about?

W: I think it influenced the way I wrote about queerness. I think being back in the south was interesting because when I left the south I was “straight.” And when I came back I was in this very visible queer/ trans relationship. There are many queer couples who are not visible in quite the same way as my partner and I are.—like for instance we got seated in the very back of a fancy restaurant once, and no one there (except one nice waitress who gave us a free bread pudding to go) wanted to serve us.. And it’s New Orleans. It’s not like there aren’t lots of queer friendly people in New Orleans.

S: It’s just weird though because it’s still Louisiana which you forget.

W: It’s still Louisiana. And I feel like that’s a thing you’re not supposed to say—but it’s true sometimes. So that apprehension was in the air, and that’s why I wanted to write about a character who had zero worry or fear about being gay.

S: When I think of New Orleans I think of it as being decadent but also haunted at the same time.

W: It is! I didn’t believe in ghosts and then the first place that I lived there seemed very haunted. The first night Jeanne [my partner] and I slept there we had identical dreams where the ghost told us that we seemed fine so it was okay for us to live in the house.

S: That’s terrifying.

W: It’s the only place I’ve ever lived that felt weird. I think the mindset of paranoia and uncanniness is easier to conjure up in New Orleans than in a very “realist” city like New York.. New Yorkers do not want to hear about my ghost chorus. In New Orleans I would tell people about my house being haunted and they would be like “yep.” Also I feel like, Prophet Fever’s not set in a swamp, but the sweetness and decay, a lot of that comes from being in this very tropical place. And New Orleans is beautiful, but everything is also falling in on itself all the time. I felt more capable of letting my work shape itself while I was living there. I was able to cede control a bit which is hard for me, but New Orleans is not a city that runs on time or lets you keep your original plans.

S: So what are some of your other influences as it relates specifically to this project?

W: In the book the wolf is named Lyra, like in the Golden Compass.

S: I was going to bring up the Golden Compass! But the idea of a sinister maternal figure one of the first things I think of is the Golden Compass.

W: Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy is pretty influential to this project. Jeff Van der Meer is a huge influence. Mostly because he doesn’t feel the need to privilege humanity over other species in his writing. He’s also a straight white man who does a really good job with queer characters and characters of color (in genre fiction no less!) which is something I really admire. Feng Sun Chen’s poetry , in particular her collection The Eighth House, is fantastic . I love how she inhabits a multitude of voices. The way Richard Siken’s Crush deals with violence in queer relationships—that book has really informed how I write and examine power dynamics.

Zombie movies—on some level, I do want this project to be a poet’s Dawn of the Dead. My fantastic D&D group, who I dedicated this chapbook to. David Bowie., in particular his album 1984 and “oh you pretty things.” Femme boyhood, as it relates to my own experience of transness or the experience I might have had if I’d come out sooner, is something I want to dig into more with Wren’s love interest, B, in the larger story.

Sarah Bridgins lives in Brooklyn. Her work has appeared in Tin House, Buzzfeed, Bustle, Luna Luna, Sink Review, and Big Lucks among other journals. You can read more of her work at sbridgins.tumblr.com.

Wren Hanks is the author of the forthcoming chapbooks gar child (Tree Light Books) and Ghost Skin (Porkbelly Press). They were a finalist for Heavy Feather Review’s Double Take Poetry Prize, judged by Dorothea Lasky. Their recent work can be found in Arcadia, Bone Bouquet, Hermeneutic Chaos, and The Boiler, among other journals. An associate editor for Sundress Publications, they live in New Orleans with their girlfriend, two cats, and a collection of sea ephemera.

BY MICHAEL J SEIDLINGER

This is an except from "Falter Kingdom."

I read somewhere that symptoms shouldn’t start until nightfall. I call bullshit on that because it’s one p.m. and I’m hungry and locked in my room. The doorknob won’t turn and, yes, it’s unlocked.

It’s messing with me and getting stronger and bolder and meaner every day. I send everything above as a text message to Becca, who immediately replies with this exclamation point, three of them actually, and then:

“I heard! That’s like such bullshit!”

Duh. I text back, “I’m home with it.”

“Are you okay?”

“See previous message.”

“Wait, like, you’re stuck in your room?”

“Yeah,” and I add, “It’s cold in here.”

Becca texts back, “We need you to meet someone today.”

“Ditch school and help me. I’m clueless with this shit.”

It’s true. I can’t believe it, but yeah, I really do need Becca’s help. But everything I just said feels so fake, and wrong, and nothing at all sincere. But it’s there, so that’s something.

“I’ll leave at lunch period.”

Good. I want to text back, “I’ll be stuck in a room haunted by some demon, waiting for you,” but instead I text, “Thanks.” And again with the “Love you.”

We both text the same two words to each other.

It feels as strange as ever.

But Becca doesn’t ask about the party the other night. She doesn’t even act suspicious. Maybe she’s caught wind of the Nikki thing but she won’t say anything about it. I think it has a lot to do with how she’s reacted to what’s been happening. For being someone so close to me, she shouldn’t have done that, keeping her distance and stuff. But then she’s also skipping school and she never skips school, so . . .

I’m confused. What else is new?

I know you’re there, yeah.

I can sense it nearby, but it’s weird because I can’t get a make on where it’s standing. It feels like it’s everywhere around me. But it’s also not doing anything. It just wants to keep me here, in this room.

Like if I left the room I’d do something stupid.

I look up from my phone and shout, “Are you protecting me or some shit?”

I hear a creaking coming from the floorboards, kind of like how the floorboards creak when I shift my weight from one leg to the other. A low creak, and then there’s nothing.

I get a text from Brad. I don’t read it.

It’s probably just a bunch of “Bro, you got suspended?! That’s fucking wild! You the man!” kind of stuff.

I try the door, still not budging.

I sit on my bed, laptop open, and I start scrolling through blog posts and other stuff. Just wasting time.

Blaire texts me, “Halverson’s a douche.”

I text back, “Yup. Douching it up.”

Blaire replies, “You’ll be okay.”

“Yeah, I think so.”

“Talked to Becca. She’s on her way.”

I read that text again and again. Something about it . . . how it makes me picture everyone I know soaking in the drama that’s probably happening, and they’re all running around, exaggerating their concern, so that they also get some attention. That’s probably happening. And then I think of Nikki, picture her sitting at a table in the cafeteria, watching as Becca and Blaire make a scene. Everyone knows what’s going on.

And here I am, freezing and stuck in my room.

I get a call. When I look, it’s a number I don’t recognize.

Well then, ignore.

But the number keeps calling. I put my phone on silent. I go online and focus on something else.

This is all getting so overwhelming.

Becca messages me online, telling me that I’m not answering her texts.

“Yeah, getting overwhelmed by things.”

“Gotcha,” she types, “on my way. Father James is cutting us like a huge break. I think he’s going to be the one that sees you.”

“Great,” and then I add, “Yeah, that’s really great.”

Becca asks, “Still locked in?”

“Yup,” I type back. Then I add, “Might have to leave via the window.”

“That’s like so fucked up,” she says.

“It is, yeah. I don’t understand what’s going on.”

“But we do know what’s going on though.”

I try to make sense of it, put it in words that would make sense to her: “No, I know, I mean . . . well, it’s just like everything people said about being haunted but it’s also very different.”

Becca doesn’t type anything.

“Let me try to explain.” But the explanation doesn’t come. I type out something that doesn’t make sense so I delete it. I’m at a loss. Then I ask, “Who’s driving you?”

Her reply: “Jon-Jon.”

I should have known. I mean, it’s not a bad thing, I guess.

I type back, “Cool.”

She knows me well enough to know that when I reply “Cool” it means the opposite of cool. She knows my mannerisms but she doesn’t know how I’m really feeling. And that’s what makes me think of Nikki as the real reason I’m going to keep doing this. I’ll break up with Becca when this is all over and Nikki and I are together.

Becca types back, “We’re heading out now. Be there soon, like ten minutes.”

“Okay,” I reply.

I lean back in bed, laptop on my stomach, hands in my pockets to keep them sort of warm.

I wait—wait for something to happen.

I look at my phone next to me; the screen’s lit up, people reacting. People are always reacting.

If anyone’s confused by this, just think of how confusing it is for me. I’m full of mixed emotions. I want it gone but I also know that none of the attention would be there if it weren’t for the demon.

I think, “You are the reason I’ll be remembered.”

I expect something to happen, but nothing does.

I stare at the screen, watching the social media feed scroll with the latest from hundreds of people I follow.

Nothing happens.

I start to count each breath I see.

Then there’s the sound of someone messaging me.

I blink, realizing I hadn’t blinked in a good minute. Hands out of the pockets, I lean forward and read the message.

“They are outside.”

I look at the name of the sender but the name is mine. It’s my name.

I don’t know what to say, so I say, “Thanks.”

“The door is open.”

I read the message and then look at the door, wander over and give the doorknob a tap, then a slight jostle.

It’s open.

I look over at the laptop, breathing out a sigh that I see as a little plume, a cloud in front of my face.

When I look back the sender appears as “offline.”

I don’t have time to react though because whatever that was, it was right. They are outside. Jon-Jon’s car parked behind mine, Becca looking up at my bedroom window, waving.

I look at the phone and see a few missed calls.

Oh yeah, it’s on silent.

I switch the ringer back on, notice over two dozen missed calls and more than a handful of text messages. I run downstairs, taking along my laptop and the power cord too, because, well, I’ve learned my lesson.

At the front door, I shove the laptop in my book bag and I leave the house without looking. I don’t get a real chance to think about what happened until I’m sitting in one of the back pews of the church, waiting to be seen.

I put all the pieces together. And then it sort of makes sense, but not really. I was messaging myself?

Was that you?

RELATED: Interview with Michael J. Seidlinger on Gifs, Gender & the Apocalypse

Michael J. Seidlinger is an Asian American author of a number of novels including The Fun We’ve Had and The Strangest. He serves as director of publicity at Dzanc Books, book reviews editor at Electric Literature, and publisher in chief of Civil Coping Mechanisms, an indie press specializing in innovative fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. He lives in Brooklyn, New York, where he never sleeps and is forever searching for the next best cup of coffee. You can find him online at michaeljseidlinger.com, on Facebook, and on Twitter (@mjseidlinger).

When it comes to fiction about witchcraft, the canon is limited. That much is obvious.

Read More

BY LISA MARIE BASILE

WELP, here's Marilyn Manson reading William Blake's Proverbs of Hell. (You can read along below). Happy Halloween.

"Expect poison from the standing water..." Musician and poet Marilyn Manson reads at Dark Blushing, a poetry evening inspired by the exhibition "Luminous Paper: British Watercolors and Drawings" at the J. Paul Getty Museum. On screen is Blake's watercolor "Satan Exulting over Eve," from the Getty Museum's collection: http://www.getty.edu/art/gettyguide/artObjectDetails?artobj=75 Introduction by Amber Tamblyn; music by Timmy Straw.

Read along:

The Proverbs of Hell, from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell by William Blake

In seed time learn, in harvest teach, in winter enjoy. Drive your cart and your plow over the bones of the dead. The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom. Prudence is a rich ugly old maid courted by Incapacity. He who desires but acts not, breeds pestilence. The cut worm forgives the plow. Dip him in the river who loves water. A fool sees not the same tree that a wise man sees. He whose face gives no light, shall never become a star. Eternity is in love with the productions of time. The busy bee has no time for sorrow. The hours of folly are measur’d by the clock, but of wisdom: no clock can measure. All wholsom food is caught without a net or a trap. Bring out number weight & measure in a year of dearth. No bird soars too high, if he soars with his own wings. A dead body, revenges not injuries. The most sublime act is to set another before you. If the fool would persist in his folly he would become wise. Folly is the cloke of knavery. Shame is Prides cloke. ~ Prisons are built with stones of Law, Brothels with bricks of Religion. The pride of the peacock is the glory of God. The lust of the goat is the bounty of God. The wrath of the lion is the wisdom of God. The nakedness of woman is the work of God. Excess of sorrow laughs. Excess of joy weeps. The roaring of lions, the howling of wolves, the raging of the stormy sea, and the destructive sword, are portions of eternity too great for the eye of man. The fox condemns the trap, not himself. Joys impregnate. Sorrows bring forth. Let man wear the fell of the lion, woman the fleece of the sheep. The bird a nest, the spider a web, man friendship. The selfish smiling fool, & the sullen frowning fool, shall be both thought wise, that they may be a rod. What is now proved was once, only imagin’d. The rat, the mouse, the fox, the rabbit: watch the roots; the lion, the tyger, the horse, the elephant, watch the fruits. The cistern contains; the fountain overflows. One thought, fills immensity. Always be ready to speak your mind, and a base man will avoid you. Every thing possible to be believ’d is an image of truth. The eagle never lost so much time, as when he submitted to learn of the crow. ~ The fox provides for himself, but God provides for the lion. Think in the morning. Act in the noon. Eat in the evening. Sleep in the night. He who has suffer’d you to impose on him knows you. As the plow follows words, so God rewards prayers. The tygers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction. Expect poison from the standing water. You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough. Listen to the fools reproach! it is a kingly title! The eyes of fire, the nostrils of air, the mouth of water, the beard of earth. The weak in courage is strong in cunning. The apple tree never asks the beech how he shall grow, nor the lion, the horse, how he shall take his prey. The thankful reciever bears a plentiful harvest. If others had not been foolish, we should be so. The soul of sweet delight, can never be defil’d. When thou seest an Eagle, thou seest a portion of Genius, lift up thy head! As the catterpiller chooses the fairest leaves to lay her eggs on, so the priest lays his curse on the fairest joys. To create a little flower is the labour of ages. Damn, braces: Bless relaxes. The best wine is the oldest, the best water the newest. Prayers plow not! Praises reap not! Joys laugh not! Sorrows weep not! ~ The head Sublime, the heart Pathos, the genitals Beauty, the hands & feet Proportion. As the air to a bird of the sea to a fish, so is contempt to the contemptible. The crow wish’d every thing was black, the owl, that every thing was white. Exuberance is Beauty. If the lion was advised by the fox, he would be cunning. Improvement makes strait roads, but the crooked roads without Improvement, are roads of Genius. Sooner murder an infant in its cradle than nurse unacted desires. Where man is not nature is barren. Truth can never be told so as to be understood, and not be believ’d. Enough! or Too much!

Via Poets.org.

Jordan Whitt

Rios de la Luz is a queer xicana/chapina living in Oregon. She is brown and proud. She is in love with her bruja/activist communities in LA, San Antonio and El Paso. She is the author of, The Pulse Between Dimensions and The Desert via Ladybox Books. Her work has been featured in Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Entropy, The Fem Lit Magazine, World Literature Today and St. Sucia.

Read More

Andrew Amistad

Phoebe Rusch is a Zell fellow in fiction at the University of Michigan, where she has received Hopwood awards in screenwriting and non-fiction. She is working on her first novel. Her essays also appear on the World Policy Journal blog and in Luna Luna. She blogs at https://phoebecrusch.wordpress.com/

Read More

Evelyn Garcia

Marianna, Yevda, and Nadya are shivering up there in the sky, (like three jewels jittering inside their flying crowns, or coffins, depending on their fate). Marianna is known as the Sapphire because she is blue eyed; Yevda is the Emerald, green eyed, and Nadya is the Ruby (with brown eyes and red hair). Their fairy tale is one of war and of witches, of poverty and prettiness, of lightness and speed, of secret terror and secret victory. Their enemies call them the Nachthexen: night-witches.

Read More

BY MIGUEL PICHARDO

Outrage is exhausting. Three-day conferences in a different time zone are just as taxing. With plenty of collective outrage leading up to the 2016 AWP (Association of Writers and Writing Programs) Conference in Los Angeles, I had to conserve my energy.

I understand that there was plenty to rail against—culturally-deficient committees, poor accessibility, the tactless exploitation by Vanessa Place made worse by Kate Gale’s ranting—but I didn’t travel across the country to be swept up in polemics. When holding a conference in such melting pot of a city whose history has been marred by racial tumult, the Association could no longer afford to ignore the groups they’ve alienated in past years. And I couldn’t bring myself to knock the Association for trying. So, I loosened my brown fist into an open hand, tucked my soapbox under the table at my lit mag’s exhibit, and prepared to make the most of a conference where, for once, I felt welcome.

If you’ve ever been to an AWP Conference, you know that there are so many panels and events going on at the same time that you might wonder how far human cloning technology has come in recent years. Had I a team of extra Miguels, I would’ve attended everything on the schedule that spoke to me as Latino writer of poetry and fiction—maybe. Here’s some of what one Miguel managed to catch at the 2016 AWP Conference:

Seated at the head of a hotel conference room were Reginald Flood, Diem Jones, Elmaz Abinader, Angie Chuang, and Angela Narciso. All of these authors have in one way or another dedicated their writing lives to circumvent “the perils of publishing in white institutions.” Abinader and Jones are two of the four founders behind VONA Voices, the only writing conference/workshop in the US that focuses on multi-genre work produced by writers of color. As of last summer, VONA left San Francisco and has made Miami its new home. Flood, Chuang, and Narciso have been involved with Willow Books, an independent press that strives to promote diversity in publishing by recognizing outstanding writers of color.

The panelists asserted that, as a community, writers of color can work towards creating an “alternate canon” worthy of inclusion in national and literary discourse. The aim then is not “diversity”—a word the panelists agreed is white, politically correct code for racism—but “equity,” as put forth by Narciso. Chuang then spoke on how writers of color should avoid becoming monoliths, self-absorbed loners who have forgotten that art can build bridges between communities.

When Jones pointed out that traditional pedagogy sometimes doesn’t work for writers of color, I realized that instead of writing for just anyone who will read our work, we should be writing for readers of color instead. Before I penned my first poem, I was an English major who couldn’t stomach the Bard and whose aspirations were forever changed after reading Junot Diaz’s Drown. I didn’t find this collection in any classroom; it switched hands between me and some of my Dominican friends at St. John’s University. I then passed it on to a group of high school students I was mentoring at the time. Re-education is not only possible; it’s necessary if we wish to turn the status quo on its head.

Before fielding questions from the audience, Abinader urged the writers of color in the room to fill in the “hollowness of diversity’’ by nurturing their individual voices and to always “make them [white people] uncomfortable.”

Will do, Elmaz. After all, change is hardly change unless it’s uncomfortable.

Four years ago, when I still lived in New York, I’d often check out a reading or a slam contest at the hallowed literary hub that is the Nuyorican Poets Café. I’d sometimes take my high school students along as a field trip. More than once, they left the café so inspired that they’d recite their own poems on the R train back to Queens. The panel at this year’s AWP showed me that the Nuyorican still has that same impact on young poets.

An institution of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, the Nuyorican has been home to a community of poets since 1975. The AWP readers—Xavier Cavazos, Ava Chin, Crystal Williams, and Regie Cabico—represented a living snapshot of the Nuyorican’s 90s heyday. Since then, they’ve earned fellowships and PhDs, won national slam competitions, appeared on HBO’s Def Poetry Slam and NPR’s Snap Judgment, and of course, published multiple books. However, they all agreed that none of their achievements would’ve been possible without the Nuyorican, their “first MFA.”

Each poet recited a piece and followed it with some recollection of what the Nuyorican did for them as budding artists. Cabico, a queer Filipino American slam poet, said that without the Nuyorican he would have been a massage therapist or a lawyer. Chin credited the Nuyorican with giving her the space to explore language as a first generation Chinese American. Williams broke down the three lessons she learned about slam at the Nuyorican:

1. If you’re going to read a poem, then read a poem. Make sure that it has all the craft and technical considerations that go into creating poetry that is meant to be read aloud.

2. Slam with the intention to connect with your audience.

3. Come original. Be your full-throated self.

Last, and most memorable, was Cavazo’s reading. Taking a cue from Williams’ lessons, he launched into a hilarious poem titled “Motherfuckers” without the delay of unnecessary preamble. The piece was a tirade against Miami Marlins’ former manager, Ozzie Guillen. No matter where I go, the 305 follows. But his poem is not what stuck with me. Recalling his days as an addict, Cavazo said he owes his life and his sobriety to the friends he made within the Nuyorican’s brick walls, his fellow panelists. Teary-eyed, he reminded us that, “Slam is not an aesthetic; it’s a community. Keep it whole. Keep it beautiful.”

A Q&A followed, unlike any I’d ever seen. A Japanese American teen from Orange County raised his hand not to ask a question, but to make a request. He had a slam competition coming up, and was wondering if he could practice his piece for the audience. The panelists could not have been happier to oblige and invited him on-stage. As he read, I was reminded of my students back in New York. It was a relief to see, to hear that the oral tradition of slam poetry is alive and well from coast to coast, as relevant today as it was in the 90s.

This year, the Association’s efforts to be more inclusive were apparent without coming off as pandering. Special accommodations were made for disabled attendees and panel titles were rife with acronyms like WOC and LGBTQ. The most apparent reforms could be seen in this year’s caucuses. At the end of the conference’s first two days, caucuses were held where groups of writers communed to discuss the challenges and opportunities their demographics face in the current publishing landscape. Caucus groups included writers in low residency MFA programs, Indigenous American writers, Asian American writers, and writers in recovery. One caveat about these caucuses was that many were held simultaneously. So someone who identified as say, a queer woman who teaches high school, would’ve had to prioritize one of these identities as her way into a larger community of writers.

I attended the Latino caucus where each panelist represented a different facet of the literary world. Emma Trelles, an alumna of FIU’s MFA program, spoke for the journalistic obligations a community of Latinx writers has in order to foster an atmosphere of good literary citizenship. She urged us to query editors for reviews on books by Latinx authors, and to cover each other’s events. Francisco Aragon, director of Letras Latinas at Notre Dame, suggested ways we can foster relationships with existing institutions in order to create literary programming and events focused on works by Latinx authors. Co-founder of the poetry workshop CantoMundo, Deborah Paredez invited us to “self-interrogate” in our work as a means of surveying the isolation we experience inside and outside of institutions. Moreover, she reminded us that “we are not exceptional Latinos; we’re representative of them.”

Lorenzo Herrera y Lozano, editor of several Latinx anthologies, posed the important question: “What would it take to publish ourselves into being?” The answer was provided by the following panelist, Ruben Quesada. Representing the literary magazine world, Quezada has held decision-making positions for publications like Codex Journal and the Cossack Review. Whenever he noticed a lack of Latinx representation in literary magazines, he either started his own or changed a predominately white one from the inside through what he called “deliberate editing.”

Quezada’s talk resonated with me especially. As the Latino editor of a literary magazine, I’d love to edit deliberately, but we simply don’t receive too many submissions from Latinx writers. During the Q&A, I made this known to a room full of strangers who looked like me, who spoke my first language. Before the Latino Caucus was over, my magazine’s Facebook page saw a surge in likes and the inbox was hit with questions about submission guidelines and book review queries.

If that’s not community, I don’t know what is.

Despite the overwhelming kinship and empowerment I felt in that room, I knew this could be the first and last Latino Caucus to ever be held at an AWP Conference. Sure, Latinx authors are as visible as ever, but being visible and being sustainable are two different feats. Before this caucus becomes an annual event, the Association asks that we jump through a series of hoops. For one, there must be panelists to preside over future Caucuses, each of whom have to have attended the last three consecutive AWP conferences as paying members. Also, the Association wasn’t concerned with how many people attended the Caucus; they just wanted the minutes when it was over. Only after the third Latino Caucus, to be held in 2018, does it become a permanent panel on the conference schedule.

Regardless of the shaky foundation the Latino Caucus stood upon, I still felt that I’d found my literary tribe, one I never knew could be available to me.

This event could not be found on any official AWP listing. Invite only. I came as a dear colleague’s plus one. After enduring a lame, ill-planned reading, we called an Uber to take us to Ladera Heights, AKA the Black Beverly Hills. Live drums and saxophones could be heard as we pulled into the driveway of one of the nicest houses I’d ever been invited to. We were greeted at the door by our co-host’s father, Mr. Barnes. Inside, the rooms were adorned with paintings and wall-to-wall bookshelves brimming with knowledge. I imagined that this must’ve been such a nurturing environment for a poet like Aziza Barnes to call home.

I leaned over to my colleague and whispered, “I wish Mr. Barnes was my dad.”

Mr. Barnes gave us the lay of the land: where to find the booze, the coffee, the snacks, and the pièce de résistance, the taco bar. The hospitality was on one hundred thousand; I was exactly where I needed to be.

The band played Motown classics as I made trip after trip to the taco bar. I spoke with young black, white, and Latinx poets from all over the country. I even reunited with a poet from Mississippi I met during the 2015 conference. We agreed that the Association had taken the hint since last year in Minneapolis, where the melanin-deficient panels and attendees made us seriously question what we were doing there in the first place.

I struck up another conversation with a black poet and PhD candidate from Flint, Michigan. Maybe it was the festivities, but like me, he was overjoyed to see so many writers of color sharing such a memorable night. He told me about Claudia Rankine’s moving keynote address, which I’d missed the night before. We exchanged email addresses and poems. The band played their last notes and then we heard the announcement, “They’re going to read.”

An unveiling was upon was, the reason why we’d all come together. Nabila Lovelace and Aziza Barnes had organized The Bash as the joyful inauguration of a new literary institution they’d founded and dubbed “The Conversation.” The organization’s mission is to “carve out a space for Black Americans to contend with their Blackness and its infinite permutations in the South.” Lovelace and Barnes wanted to turn the literary conference model on its head, and by throwing The Bash, they had done so beautifully, in a manner no POC I know could resist: the house party.

Our hosts stood silently in front of their mic stands, commanding us with their presence before either of them spoke. Lovelace’s head was wrapped in a soft cloth and Barnes wore a plaid blazer, dreads draped over her shoulder. Barnes thanked all of us for attending and stressed the importance of coming together outside of the Association’s confines. She went on to read a poignant piece about being harassed by LAPD outside of the very house we were gathered in—the house she grew up in.

After the reading, the band packed up their equipment. Yet, the party was far from over. A DJ set up his gear and turned the Barnes living room into one of those basement parties from my high school days. The lights were low, the floor was shaking, and bodies moved to anthems like Montell Jordan’s “This Is How We Do It” and Juvenile’s “Back That Azz Up.” When Dark Noise Collective poets Danez Smith and Nate Marshall busted out a flawless “Kid ‘n Play” in the middle of the dance floor, the crowd lost it.

I swayed to the music, getting by on my two left feet and reveling in the ruckus we were busy making. Amid a conference that was anything but silent, the noise of change had been a low hum since I arrived in Los Angeles. Here, at The Bash, it reached its crescendo.

The DJ threw on Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright,” and played it loud. All of us chanted the chorus together, “We gon’ be alright/ Do you hear me, do you feel me? We gon’ be alright.”

I couldn’t agree more.

Miguel Pichardo is a Dominican/Ecuadorian writer out of Miami. His poetry has appeared in Duende and Literary Orphans. He is currently an MFA candidate at Florida International University and the editor of Fjords Review.

BY JOANNA C. VALENTE

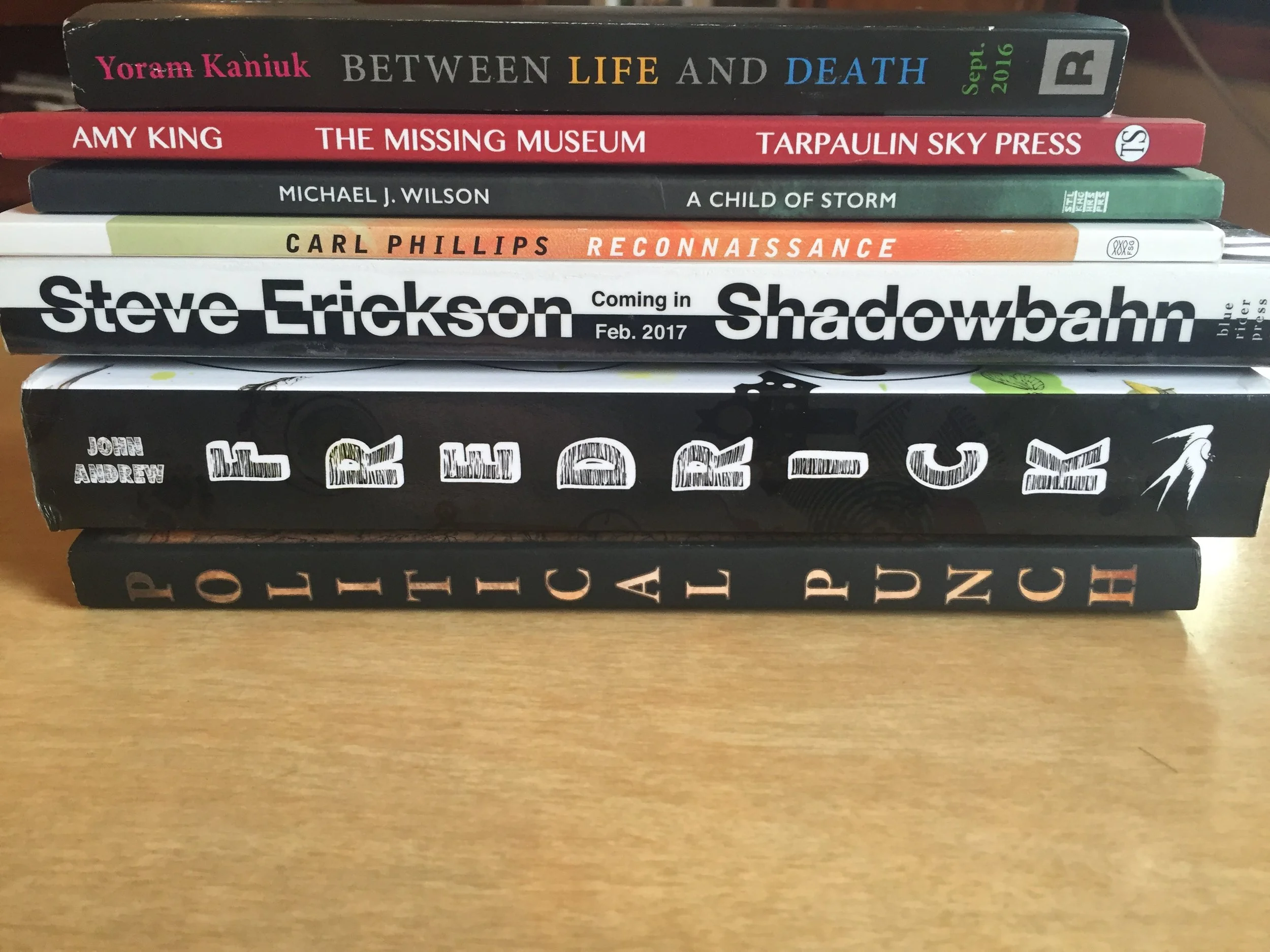

1. Between Life and Death - Yoram Kaniuk (Restless Books, 2007/2016)

Excerpt from Lit Hub:

"Near the house, right across from the calm hidden beauty where I searched for a gutter to play me the lullabies of my childhood, a little bit of sea is still open. Moshe my father would swim in it every day at exactly five in the afternoon, after most of the swimmers had already gone home, because he loved having the sea all to himself. In the spring and fall, the sea was sparkling and smooth and soft, and sometimes in the morning, on the way to school, we’d walk barefoot in the sand along the shore, and under the hewn-limestone wall, we’d take off our shoes, hang them by the laces on our shoulder, put our schoolbags on our heads like the Arab women who carry ewers of water and bundles of wood to the ovens, and we’d walk in the shallows lined with seashells, some were broken and cut our little feet, until we came to the sand dune across from the Model School."

2. The Missing Museum - Amy King (Tarpaulin Sky Press, 2016)

From TS' site:

"AND THEN WE SAW THE DAUGHTER OF THE MINOTAUR

Poet, comma. It is thus the delay,

which is also a beginning. That we can link eyes

across her time-space continuum is another hyena.

The female elongates, bares fangs, and a trash

compactor recycles. Hyena gives

in the recycling fashion. Phoenix, no more false

flight from holes; now balloons eating decay.

Hunger denuded us, too. But will you give

up your death for me? With surgery, I outright hollow

the monster to breathe across windows. I don her hollow

whole. She writes back in the pauses of haze.

Her and her tragic magic. We are all cross-dressing

in tiny wings with the machines of bones to go on."

3. A Child of Storm - Michael J. Wilson (Stalking Horse Press, 2016)

Sensitive Skin Magazine published four poems from the collection:

"Edwin Davis & The Electric Chair

Brown came with a crate.

The kind milk bottles condense in.

He sat it down. In the center of the room.

I had spent the day clearing cobwebs, a rug.

I used parts of the crate to make the chair.

Stringing the wires, using the Edison diagram

The Brown instructions.

I shot 1000 volts through Kemmler

then again until he burst to flame.

The skin around the metal became leather.

They would have done better using an axe.

I shot volts into a woman. Into the man who shot McKinley.

I got to meet J.P. Morgan. Twice.

Every time –

The smell –"

4. Reconnaisance - Carl Phillips (FSG, 2015)

ead an interview with Phillips at NPR:

"I have, from the start, been writing about the body and power. And maybe more specifically, the gay male body, and power in intimate relationships, but I feel as if there's a lot of overlap with society's views of how different bodies are treated. So to that extent, I think there's always a kind of political resonance to the personal, and then vice versa."

5. Shadowbahn - Steve Erickson (Blue Rider Press/Penguin, 2017)

It's exactly what we need right now - a book set in a tragic political landscape along to a playlist to give song to the time we live in now - one of strange turmoil and uncertainty. All of the characters are on a journey of self-discovery, and the reimagined Twin Towers represent this. It's definitely a book to pick up once it's released this February.

6. The King of Good Intentions II - John Andrew Fredrick (Rare Bird Books, 2015)

Read an interview with Fredrick at LARB:

"I think the books are failures too. Brilliant failures, of course. And again I don’t mean brilliant in the look-at-me sort of way, but brilliant in the sense that parts of them (and I hope the preponderance of them) truly shine. As comedy. And very very human and humanist. Isn’t that enough? Yes, I revised the first King five times. The hardest work I have ever done. Much harder than writing a dissertation on Ford Madox Ford and Virginia Woolf. I just got sick of looking at The King II, I revised it so much. I’m a Jamesian and a Joycean. I could revise all day — trying to lift the prose into poetry, trying to make the jokes zanier and tighter. There’s nothing wrong with failing. Failing is an energy. And in a way, paradoxically, the books are not failures and I am being very disingenuous about the records. You shouldn’t trust me; I’m an unreliable narrator in real life, too."

7. Political Punch: Contemporary Poems on the Politics of Identity - Edited by Fox Frazier Foley & Erin Elizabeth Smith (Sundress Publications, 2016)

Read an interview with both editors over at VIDA about how the anthology came to be. Foley stated:

"My feeling about this are complicated, and kind of conflicted. I think of poetry in the same way that I think of prayer. I’m a religious person, so to me, prayers are actually a significant factor in seeking any type of progress, including political or social progress. Prayer and poetry, to me, are both ways of centering your consciousness, and raising both your focus and your energy. They are both, on some level, ways of howling down the parts of the Universe that we don’t entirely understand (I mean, we might name them, or tell stories about them—but I think all religious apparatus is really just a way of making somewhat intelligible to us the forces that are beyond our rational comprehension) to please come to our aid in helping us fix this situation. Prayer and poetry both bring people together, too—one person’s words can forge connections among many people, so that ultimately both a poem and a prayer can result in focusing the energy and consciousness of larger groups, in a way that creates a feeling of solidarity. To me, all of that is integral to political and social progress. I understand that not everyone sees it that way, but speaking for myself and my own lived experiences, that’s how I understand it."

CA Conrad's poem in the collection is amazing; excerpt from “act like a polka dot on minnie mouse’s skirt:”

"i am not a

family friendly

faggot i tell

your children

about war

about their tedious future careers

all the taxes bankrolling a

racist tyrannical military."

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. She is the author of Sirs & Madams (Aldrich Press, 2014), The Gods Are Dead (Deadly Chaps Press, 2015), Marys of the Sea (forthcoming 2016, ELJ Publications) & Xenos (forthcoming 2017, Agape Editions). She received her MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. She is also the founder of Yes, Poetry, as well as the managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of her writing has appeared in Prelude, The Atlas Review, The Huffington Post, Columbia Journal, and elsewhere. She has lead workshops at Brooklyn Poets. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente

via Women of Faith

deziree a. brown is a black queer woman poet, scholar, activist and self-proclaimed “social justice warrior” from Flint, MI. They are currently a MFA candidate at Northern Michigan University in Marquette, MI, and often claim to have been born with a poem written across their chest. Their work has been recently published in the anthology Best “New” African Poets 2015, Duende, Crab Fat Magazine, and Razor. Twitter: @deziree_a_brown

Read More

Adrien Coquet

Meg E. Griffitts' work has appeared or is forthcoming in Hypertrophic, Evening Will Come, The Colorado Independent, andBlazeVOX.

Read More

Meghann Plunkett is a poet, performer, coder and feminist. Her work has appeared in national and international literary journals including Muzzle Magazine, The Paris-American, Simon & Schuster's anthology Chorus, and Southword. She teaches creative workshops at Omega Institute and co-directs a children's summer camp called Writers' Week Aboard the Black Dog Tall Ships in Martha's Vineyard. Currently, Meghann is an MFA candidate at Southern Illinois University.

Read More

Everyone seems to know who Michael J. Seidlinger is, even if just by name. Seidlinger is a ghost — the kind of ghost who messes up you book case and reorders everything so you can't actually find what you're looking for. But then when you actually look back at all of the reordered books, you find something beautiful stuck in there that you hadn't seen before.

Read More

El Yas

Sometimes, I feel sad when I look back through old photo albums. There are so few of me beyond the age of 12 that it is occasionally difficult to even remember what I was like then. What happens, because I am so undocumented, is that all I remember is being sad, fat, unhappy, uncomfortable. I know that’s not how I felt every day. Yet, it’s all I’m left with.

Read More