Black Hollyhock, Atoosa Grey’s first poetry collection, faithfully adheres to its title. While voluptuously organic, it also contains a dolorous underside. Grey’s image-driven poems, imbued with symbolism, navigate territories within territories -- those of language, identity, motherhood and the body. She deftly renders a world nuanced with languid musicality and replete with questions. She asks us to consider the currency of words, to find the sublime in the mundane, and to recognize the inevitability of rebirth and resurrection throughout our lives: “The body has its own way of dying / again / and again.”

Read MoreThe Trials of Writing Haibun About the Salem Witch Trials

Hands down, the best decision of my life was joining a low-residency MFA in Creative Writing program. When I think about my experience, I imagine Mike Teavee from Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. My poems, like Mike, started out normal sized and a bit naive. Then they shrunk. This tiny poem phase didn’t so much reflect the length of the verse, but instead the humbling of my ego. Everywhere I went, I met beautiful poets and read amazing collections. I currently take in every bit I can of anything that might even closely resemble a poem so that my tiny, metaphysical mind-poem can grow. And that’s just what it’s doing.

Read MoreDara Scully

Nightingale And Swallow Part II, Fiction By Taylor Sykes

When he’s back in the store and I’m alone again, I let myself lean into the worn leather steering wheel, clinging to it like a body. I can’t keep myself from crying when I think about that boy and what Caroline did to him. So I cry until it rains and then until it rains harder, until the sound of wind and water striking the truck is louder than I could ever be.

Read MoreDara Scully

Nightingale And Swallow, Part I, a Fiction Piece by Taylor Sykes

His lips look purpled already, but it must be the moon’s coloring coming in from the window. I push a puff of smoke into his spit-soaked face. It hits like a burst of water. Then comes the heft in my chest, a weight the size and shape of a fist. Before I can think too much about it, I push him on his side, face down.

Read Morevia Ghost Diaries

Poetry By Kevin O'Connor

so that the petals bleed in darkness

where a child overturned a bag

via Goodreads

What My Compulsion to Write Actually Means

I’ve thought a lot lately about writing as an inherently inward and narcissistic act--my thoughts, my interestingness, my hidden depths. Joan wrote that we spend our lives being told we are less interesting than everyone around us so I write: It is nighttime, and I am in Rome, pretending everyone around is far less interesting than me.

Read MoreA Review of Poetry Collection "In Leaves of Absence: An Illustrated Guide to Common Garden Affection"

In Leaves of Absence: An Illustrated Guide to Common Garden Affection (Red Dashboard Publishing) with poetry by Laura Madeline Wiseman and art by Sally Deskins, our capacity as women to thrive or wilt, is revealed through daily garden life. In between these detailed poems and exuberant paintings, there are paragraphs of facts and plant history, to teach and temper the budding words. It is a reminder that caring for nature, like caring for a person, is an investment. As Wiseman writes in “The Family of Magnolias,”

“planting the wrong tree or doing it in the wrong way is something better left undone.”

When one plants a tree from seed, it is a lifetime commitment or at least half a lifetime. The gardener is caregiver: watering a seed, protecting a sprig from frost, watching for signs of disease or insect invasion. After many years a tall sturdy tree is a crowning achievement while a failed plant can be heartbreaking. Like life is with relationships. Yet we plant again in the spring, measure out garden plants, look for new loves. To garden is to hope. All living things, however, die, or “leave,” eventually. But isn’t biting an apple or smelling a rose worth it? Wiseman and Deskins explore this journey through these intricate poems and bursting water colors.

One of the first metaphors in the collection is “A Wrong Tree.” The tree is almost described as a stumbling Civil War soldier, suffering without anesthetic:

“Limbs are sawed off as amputated stumps and oozing wounds.

The canopy won’t shade you no matter where you stand.

…Evenings on the lawn chair you slouch with cheap beer.

You gaze at the green lawns around you—

You imagine hopping the fence to a new home…

I could leave…”

We assume the underdog status through “A Wrong Tree,” judging it’s low hanging branches, it’s lack of leaves and structure. The tree is a symbol for living the wrong life: the wrong yard, wrong car, wrong house, wrong neighborhood. We hunger for the other: the perfectly manicured lawn or mini barn shed. Even though disdain is present for this ugly duckling, there is some sympathy. The tree is surviving, it does not appeal to the masses, have “curb appeal.” But it is unique. These hiccups in nature reflect on our own quirks and flaws as humans. We must “go on” too, no matter what.

Deskins splatters her drawing of “A Wrong Tree” with the brightest colors imaginable: greens and blues, pinks, and oranges. Her tree is a helpful reminder that beauty is found in unconventional shapes and places.

Likewise, another painting that shines with self-love is “Take Leave.” (There is lots of “leave” and “leaf” word play throughout the book and one can also not help but think of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass while reading these poems.) In the painting “Take Leave,” a curvy female shape stretches her limbs within a tree trunk. She is proud, blissful to enrapture the tree’s magic, her torso blending into the bark. She is serene and one with the tree. It is powerful.

Today, with all women’s rights and freedoms under attack this image is refreshing. If only all women could arch their elbows to the sky, strong: feel their power. This painting is a wish.

In the following two poems: “Leave off Husbandry,” and “Weeping Hawthorn, A Friend and Neighbor,” tree and woman blend but manifest that all allusions to trees are not beautiful. In “Leave off Husbandry,” Wiseman writes:

“you axed us in my dream. I awoke

to my heart scudding, a thicket of birds.

Your will to destroy left me shaken…

I was putting out roots, leafing at the base.”

Arms are swinging an imaginary ax., cutting off our limbs, our ability to run, our ability to flower. Giving something “the ax” is a synonym for finishing it. Wiseman uses the tree as a symbol in this relationship, the stress dream pulling intimacy’s roots out of the ground. The tree is powerless to the ax, does not see it coming, like anyone blindsided by an emotional trauma. (Again Deskins paints an effective image to be paired with this poem: a flesh colored woman, slumped by a tree, looking over her shoulder at the reader, forlorn.)

In “Weeping Hawthorn…” the natural world is a metaphor for assault. Wiseman writes:

“her limbs bent to his need, a hot, blind

forcing that once opened would scar.

She scratched at him to stop…”

“…Each of us wants

to blossom, grow, ripen, be

plucked—consent—never like that.”

Through representing the women as trees, the reader experiences not only how our environment cannot speak for itself, but also how women are silenced, how casual violence is prevalent. Like a new sapling, a girl, a woman should be cared for, should feel free to shout her voice to the world, not prove how her existence should just be tolerated. At least the trees have the forest.

Whether these poems are witnessing women’s plight, or a childhood memory (Wisemen playfully quotes “let the wild rumpus start,” from Where the Wild Things Are and there are allusions to a swing hanging from an oak tree,) or exploring word play, Deskins accompanies these fevered words with light and spirituality.

In “Common Prayer to Tree Gods and Goddesses,” the outlines of women are in a forest with the orange/reddish colors atop the tree canopy. One does not know if it is dawn or dusk and it doesn’t matter. These tree spirits are timeless.

Our tree lined streets or lone tree in a yard or tree standing tall in a park are us. Wiseman teaches us the mind might forget certain slings and arrows, but “…the body can remember what we carved.”

This collaboration is a tour de force of word and color, a wonderful blending hybrid creation, as can only be found in nature.

Jennifer MacBain-Stephens went to NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts and now lives in the DC area. Her chapbook “Clown Machine” is forthcoming from Grey Book Press this summer. Her first full length collection is forthcoming from Lucky Bastard Press. Recent work can be seen or is forthcoming at Jet Fuel Review, Pith, Freezeray,Entropy, Queen Mob’s Teahouse, Right Hand Pointing, Cider Press Review, Inter/rupture, and decomP. Visit her here.

Rebecca Melnyk

Interview with Poet Leah Umansky About Her New Chapbook 'Straight Away the Emptied World'

Leah Umansky is a force of nature--and she's not about to be stopped either. She's the author of three collections: her full length book "Domestic Uncertainties," (Blazevox, 2013), a Mad Men inspired chapbook "Don Dreams and I Dream," (Kattywompus Press, 2015) and now her dystopian-themed chapbook "Straight Away the Emptied World," out by Kattywompus Press this month.

Read MoreAela Labbe

Poems by Anne-Adele Wight

Review of Rebecca Kaiser Gibson’s 'Opinel'

While I was admiring the navy blue of the Atlantic a few weeks ago in a secluded Cape Cod house, I hungrily read Rebecca Kaiser Gibson‘s “Opinel.” It is a poetry book full of majestic, dreamlike imagery set in an all-too-real world. Published in 2015 by Bauhan Publishing, it centers around both urban and rural landscapes, mythical and mundane lives; it is a book that speaks well of loneliness, using the earth as both lover and enemy.

Read MoreOn Needing Diverse Books, Cinderella & Feminism

BY MACEY LAVOIE

I grew up in a world of VHS tapes and Disney Classics. My collection was an impressive mass of bulky nostalgia that I packed away as DVD’s took over. I remember my favorites: the brave Mulan and the heart-wrenching tale of Simba in the Lion King. But one thing is for sure, I have always hated Cinderella.

My family would laugh at my utter lack of interest in being a Disney princess, but from a young age something about the tale of the girl in the glass slipper irritated me. Cinderella did absolutely nothing to help herself, and it could be argued that if the fairy godmother hadn’t shown up Cinderella would still be scraping the cinders out of the fire. It was a classic damsel in distress story that even as a child I couldn’t get behind.

Via here.

During that time I wanted – needed – a story that would show a healthy representation of women, especially a gay character, one who struggled and faced adversity but was able to overcome it. Such a character didn’t exist (at least to my knowledge), so I stopped reading the few LGBTQ books my friends would suggest to me.

Though my family had never spoken ill of LGBTQ individuals they didn’t outwardly advocate for them either. It was a topic that rarely found its way into conversation. I remember the truth being at the tip of my tongue, and I remembering swallowing it down as I recalled all the scenes in books where the truth caused nothing but heartache and disappointment. I would clench my hands under the table and the truth would slip back down. My mother would ask me what I was thinking and I would only shrug my shoulders: nothing much.

It wasn’t until I received a book for Christmas that my perspective of the much-loved character began to change. “Ash” by Malinda Lo is an adaptation of the Cinderella – it's got faeries and huntresses. It was this tale of magic and self-discovery that led me to consider what it would be like to put on a pair of glass slippers of my very own. Though, in this version, Ash doesn’t fall for a prince or even a man; she falls for the King’s Huntress, Kaisa.

This was my first time reading a book where the main character was bisexual and encouraged to be herself, with a complex love triangle between a mysterious faerie named Sidhean and Kaisa. I was swept up in the love story because it was something I could relate to. I identified as someone apart of the LGBTQ community and was comforted to know that – for once – the fictional characters I spend a majority of my time with reflect a part of me you don’t see represented often.

Much like Ash, I wasn’t one of those children who inherently knew about their sexuality early on. I pretty much tripped into it my early years of high school much like Ash trips into it upon discovering her romantic feelings for Kaisa. You rarely see gay characters in literature, much less a bisexual character that ends up falling for a woman.

LGBTQ books have been problematic, to say the least. The main character typically discovers their sexuality and is disowned, kicked out of their house or ostracized and bullied to the point of suicide. I remember reading this scenario over and over again until a seed of doubt was planted in my own head. Would my kind and loving family really kick me out if they knew about me? Was it that bad to be different?

Lo's version of Cinderella, however, speaks of a quiet strength, and more complexity than the original. This is a Cinderella character I could get behind. One who was kind but also brave, one who got lost in books and didn’t need to fall into the arms of a prince to be saved.

The topic of representation has been a hot spark in the publishing world for a while, as more organizations like VIDA and We Need Diverse Books gain momentum and as diverse voices are published. I can only hope that we see more writing like this come out of the woodwork.

Macey Lavoie is a new Bostonian trying to find her way around and working on her MFA at Emerson College. She has a fondness for sushi, walks on the beach, reading and mermaids. When she is not busy having crazy adventures with her friends she can be found either jotting down writing ideas in her small notebook or curled up with a book and her two cats. Her dream is to one-day change the world with a book and to own a large library.

via Poetry Foundation

Review of Ariana Reines' 'Mercury'

Ariana Reines, the Goddess of putting it all out there is a supercharged, magical she-wolf. The sweet beast’s soft underbelly and sharp black claws reside happily in her poetry. She brings to light the twists and churns of our page-surfing information obsessed sex-craved whims and deepest most petrifying wishes.

Read MoreFrom Katie's childhood

Review Of 'forget me / hit me / let me drink great quantities of clear, evil liquor' By Katie Schmid

There are things I may never know but there are things I’ve known all my life. Let me tell you something I rarely tell anyone; I knew I would have a firstborn daughter. I told my parents this growing up. I told my wife this before she was my wife. I told her this when she was pregnant for the first time. It was something more than a yearning or desire. The closest word I have for this feeling is faith.

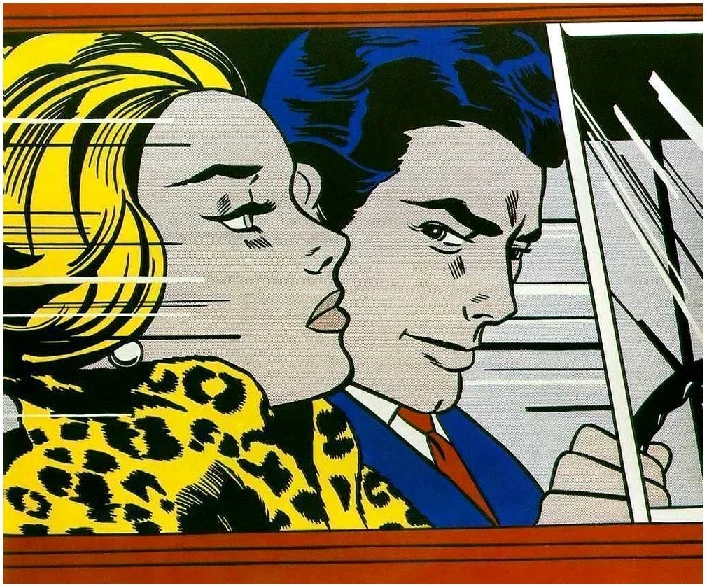

Read MoreRoy Lichtenstein

Writing the Landscape of Isolation, Trauma, & New York City

When writers talk about writing, they talk about isolation. It’s why Basquiat and Woolf and the Shelleys and Whitman and Holiday all created something with a vicious pursuit—as a means to connect. They needed to—you could say it was somewhere in their marrow or their spirit, or whatever it is you believe to be so deep, it can’t be separated from the human. So, if we’re talking about living with loneliness, what does this actually mean?

Read Morevia Boost House Twitter

Review Of 'The Best Thing Ever' By Laura Theobald

The Best Thing Ever is telling us something we already know, but are hesitant to acknowledge. We are tired. We are at work. We think about Mom and Dad. We think about death and destruction and our government. Given the multitude of topics we could be discussing with colleagues and friends over text, the same things keep coming up. We repeat ourselves and don’t even know it. The best thing ever would be to put the iPhone down. The actual best thing ever is to hear, to listen to Theobald while we still can.

Read More